BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Miep Diekmann

writer, journalist, the Netherlands

|

Miep Diekmann, May 1999,

Miep Diekmann, May 1999,

in front of two portraits

painted in (left) 1958 and 1955

in the Museum of Literature,

The Hague, The Netherlands.

Photo: Sonja van Kerkhoff

|

Born in 1925 in Assen, The Netherlands, Miep Diekmann published her first

novel, intended for teenagers, in 1947. She was one of the first Dutch authors

to focus on books for youth. Since then she has published nearly eighty

books.

Between the ages of 9 and 14, she lived with her family on Curaçao (Dutch

Antilles). This experience made a deep impact on her resulting in a number

of books set in the Antilles as well as a semi-historical novel set in the

17th century Dutch slave trade ("Marijn bij de Lorredraaiers", 1965).

"De Dagen van Olim" (1971), an autobiographical novel about a suicide

attempt after the traumatic experience of a rape attempt, focuses on how

the 12-year-old rebuilds her life and her sanity.

Her books cover a wide

range of genres, from poetry for children where 'strange' words are linked

to each other in playful ways, to a novel for youth about teenagers in a

hippy family in the Dutch '70's ("Total Loss, weetjewel", 1973) to

a non-fiction book for adults ("Een doekje voor het bloeden", 1970)

about the 1969 riots in Curaçao. |

|

She has also written

two novels with the art historian, Marlieke van Wersch, on the lives of

two boys who want to be painters in 17th century Leiden ("Hoe schilder,

hoe wilder/Leiden", 1986) and in Haarlem ("Hoe schilder, hoe wilder/Haarlem",

1988). The books lucidly tell of the historical events, attitudes and

customs of the times.

Her books have been translated in Austria, Columbia, Czechoslovakia, Japan,

Greece, Denmark, Dutch Antilles, England, France, South Afrcia, Spain,

Sweden, Switzerland, U.S.S.R, X-Yugoslavia (Croatian, Serbian, Slovenian),

East and West Germany as well as the U.S.A.

Miep Diekmann has received eleven important prizes for her work, starting

with an award in 1957 for a book set on the Dutch Antilles. She has received

the Premio d'Oro, one of the most prestigious awards for children's

literature in Europe, twice: for "Ik heb geen naam" (1982), a book

centering on the memories of a survivor in a World War II concentration

camp, and written with Dagmar Hilarová, and for "Hoe schilder, hoe

wilder".

|

Miep Diekmann aims to create a realistic view of society in her books.

She believes that children are discriminated against when areas of their

life are censored, so themes such as sexuality, death, racism and discrimination

are integrated in stories that focus on the disputes of inner life rather

than only on exciting adventures.

Individualism isn't glorified in her

books, yet it is through the thoughts of the main characters that we can

read about how the world changes or how problems are resolved.

It is important to her that children in all countries should have access

to books that might help them to process life. She has been instrumental

in the assistance given to writers from The Netherlands and the Dutch

Antilles and in promoting translations of children's books in the Netherlands

from other countries. She also believes that translating stories is important

so that children encounter other customs and can make comparisons between

their own situations, customs or ideologies and those of others, helping

them to develop more critical attitudes to their own and other customs.

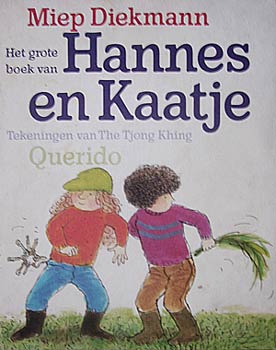

|  Cover of The Big Book of Hannes and Kaatje by Miep Diekmann, illustrated by the Indonesian born The Tjong Khing, published by Querido in 1989 (5th reprint was in 1993).

Cover of The Big Book of Hannes and Kaatje by Miep Diekmann, illustrated by the Indonesian born The Tjong Khing, published by Querido in 1989 (5th reprint was in 1993).

This is a collection of about 150 short stories based on these two children, which were published in separate books in the mid 80's. Miep received 2 national literature prizes (The Vlag en Wimpel in 1986 and 1987) for two of these books. Some stories had also been televisied for children's programmes.

|

Part 1:

(Arts Dialogue: December 1997) Miep Diekmann discusses developing a literature

for young adults in the mid '40s to 50's and her first books set in the

Caribbean;

Part 2 (March 1998) focuses on her coaching writers from Curaçao

and Aruba, and her novel set in the Dutch slave trade;

Part 3 (December 1998) focuses on "De dagen van Olim" and

"Een doekje voor het bloeden";

Part 4 (September 1999) discusses the "Hoe schilder, hoe wilder"

books and "Total Loss, weetjewel";

Part 5 (October 2001) considers her work in facilitating the publication in the

Netherlands of about 20 books by Czech writers, and about ten of her own

books published in Prague during the Cold War (1960s until 1988).

Part

One

In 1934, my father was given a position as an officer on Curaçao, in the West Indies. At the time, the East Indies (Indonesia and Papua New Guinea) were well known among the Dutch, but few were aware of the Dutch colony

in the West Indies, probably because the Dutch trade company had profited

from the slave trade.

When our family left for Curaçao, I was nine and my sister was seven.

We only knew what my father had told us: that we were going to an island

where it was warm and the people were black. Our only idea of a coloured

person was of Zwarte Piet (Black Peter), who was often portrayed as someone

for children to fear. Zwarte Piet would take us away in his sack if we

were naughty. Many Dutch children were afraid of black people, including

my sister, who was afraid of them even while we were living on the island...

My reaction to the move was “how exciting”. I think that is the artist

in me, responding positively to a new or different situation. At school,

I was placed in a class that had a majority of black children, because

the class for white children was full. I found it exciting. I remember

feeling the dark arm of my class mate while she felt my white arm, until

the nun caught us and forbad us to touch each other. We were told that

it was dirty to feel the skin of another. I was curious about many things,

and had close contact with the children in my class. But I didn’t dare

to ask them about the history of slavery. There was absolutely no mention

of it. I couldn’t ask such questions at home either, because they didn’t

know. We had housekeepers and whenever I asked them, their response was

that they didn’t talk about it.

The only books came by ship from the Netherlands, but these rarely addressed

contemporary life. I had a friend who I loaned my books to, but after

about a year, she didn’t want to read them anymore. I said “Yes, I find

them a bit boring too”, and her response was, “no, I find them mean”.

When I asked her why, she said that she always had to read about white

children and never about black children. It was a revelation to me, and

so, at the age of 12, I decided to write books about black children. I

was not really a child who wrote a lot, but this goal gave me the incentive

to write. In 1939, just before the start of the second World War, we returned

to the Netherlands. On Curaçao we lived as a wealthy family, and my father

was considered important. Back in the Netherlands, we had to adjust to

a much lower standard of living. I could speak fluent English and read

Spanish with ease, and was accustomed to being treated as the daughter

of someone important. Now, at the age of 15, I was treated as a small

child and I found that a shock. During the war, I moved a lot and attended

seven secondary schools. Another change was that my parents separated,

and I chose to live with my father....

I was 20 when the war ended, and started my career as a journalist for

a weekly commercial newspaper. The publisher also produced books and suggested

that I write fiction books, as there was a shortage after the war. My

response was to write for teenagers because there were no books aimed

at teenagers. After the war, children had to attend school until they

were seventeen, whereas before the war, twelve year olds could be working.

Many children did not have books at home, but now they had more time to

read. My aim was a social, not a commercial, one. I wanted to fill a need.

My youth coincided with the second world war, so in a sense my generation

never really had a youth. During the war, we had a lot of freedom, and

could do what we wanted as long as it was against the Nazis. After the

war, we were expected to obey our parents and conform to society’s norms.

I was 20 when the war ended, and started my career as a journalist for

a weekly commercial newspaper. The publisher also produced books and suggested

that I write fiction books, as there was a shortage after the war. My

response was to write for teenagers because there were no books aimed

at teenagers. After the war, children had to attend school until they

were seventeen, whereas before the war, twelve year olds could be working.

Many children did not have books at home, but now they had more time to

read. My aim was a social, not a commercial, one. I wanted to fill a need.

My youth coincided with the second world war, so in a sense my generation

never really had a youth. During the war, we had a lot of freedom, and

could do what we wanted as long as it was against the Nazis. After the

war, we were expected to obey our parents and conform to society’s norms.

I was enthusiastic and naive, and decided to write about the lives of

children in the Dutch Antilles, since no one knew about them. But, I began

writing about myself. When my first book, “Voltooid Verleden Tijd”

(Perfect Past), was published in 1947, the critics commented that it was

better for young people not to read it because of the opinions it expressed.

It was about a young working woman living in Amsterdam and sharing a room

with a girlfriend. What shocked the critics was that it did not have a

romantic “happy” ending, and I used the language that young people used,

rather than the formal book style that was the norm for fiction at the

time. I found it criminal that the books teenagers read always had a happy

ending, while in reality, their own relationships didn’t often end that

way. I found it wrong that fiction didn’t relate to their own lives and

concerns, and I feared that young readers might think they were abnormal

if their lives didn’t reflect what they read about. I feel writers have

a responsibility to take into account the effects their work will have

on readers. At this time, there was no education or discussion about sex

or sexuality. So, how could teenagers deal with this aspect of their lives?

I wanted to address the issues of puberty, and this shocked the critics

too...

Even

in 1971, when I wrote my semi-autobiographical novel, the international

critics were shocked because a woman was the author. My second book for

youth, “Panadero Pan” (published 1947), was set in Curaçao. The

title, which is in the Papiamento language, means “baker bakers bread”

and is the first line of a rhyme. It was my first book about the Antilles,

and now I am amazed at how political it was. As a 22 year old, I used

my childhood memories to write the story of a Dutch girl who mixed only

in the white community. It presented colonialism as something that didn’t

quite make sense. Looking back, I see that it was a pre-run for my autobiographical

work, where the challenges to colonialism as a misuse of power were much

more consciously expressed. Another ‘political’ story was “Wereld van

twee” (published 1948). It centred on a young woman who, during the

second world war, had an aunt who was senile, and when her parents heard

that the Nazis were going to exterminate all senile people in institutions,

took the aunt into their own home to care for her. After the war and after

the parents died, the young woman had to care for the aunt, but wanted

to be like other adolescents her age -to go out, dress up and so on. The

story was shocking because it was assumed in those days that young women

were only concerned with being beautiful, and had no other concerns. The

books of the time reflected these values.

Also,

the Dutch public was rather isolated until the 1960’s, when we had our

first international literature conferences. Organisations such as the

International Board for Books for the Young (IBBY) didn’t start

until later. I began work on “De boten van Brakkeput” (The boats

from Brakkeput)1, which was published in

1956. Brakkeput is in the south of Curaçao, where the fishers lived and

the plantations and expensive seventeenth century colonial houses were. Also,

the Dutch public was rather isolated until the 1960’s, when we had our

first international literature conferences. Organisations such as the

International Board for Books for the Young (IBBY) didn’t start

until later. I began work on “De boten van Brakkeput” (The boats

from Brakkeput)1, which was published in

1956. Brakkeput is in the south of Curaçao, where the fishers lived and

the plantations and expensive seventeenth century colonial houses were.

The story is about a Dutch boy, who was born there and is caught between

the world of his Dutch father, who owns a plantation, and the world of

the black fishermen, who are his friends. Matthijs is given a sailing

dinghy when he is 12. The fishermen warn him not to go near the small

island, The Hollow Tongue, because there are ghosts, and boats

disappear into the Big Mouth in the bay. But the boy decides to look on

the island and pitches his tent there, finding nothing amiss. He is a

lonely boy, and this is reflected in his thoughts on the island. One time

on his return, he is warned by a servant not to return to the island because

the fishermen have seen a black bird -a sign of bad luck. His father feels

that this is nonsense. Then visiting his tent the next day, Matthijs discovers

an exhausted man, who speaks a foreign language. Matthijs had heard at

his school that a prisoner had escaped from Devil’s island. (This part

of the story relates to the escape of Papillion, which happened while

our family lived on Curaçao. My father received a telegram that the escaped

prisoners had leprosy, so he had to make sure that they didn’t have contact

on land, while giving them medical and food supplies.) Matthijs had heard

that the doctor passed on the supplies, but had noticed that one prisoner

was missing from the boat. So when he sees the man in his tent, he realises

that he is the missing prisoner. The boy is faced with a conflict: to

help the man would involve lying and stealing.

I wanted to show how we suffer when we are faced with conflicting choices,

and yet are still able to make and act on the better choice. Matthijs

realises that the man must leave the island before he is discovered, but

knows that if he steals one of the fishermen’s boats, it would result

in tragedy because four families’ income depend on each of the boats.

So he tells the man to take his boat. Matthijs is not sure what to tell

his father, and decides to say that boats do disappear into the Big Mouth

in the bay.

In doing so he has chosen to identify with the culture of the fishermen.

The story ends the following morning.

“Once

upon a time - that wasn’t even so long ago. Only just before his birthday.

Along with the ‘Eline’ he had also received the Hollow Tongue. An island

all to himself. And the ‘Eline’...

He didn’t want to look at the empty block, but he could not help doing

it. If you close your eyes real tight, then you could imagine how the

sailing dinghy lay on the sand, glistening golden-brown in the sun. He

could still see the tiller as it had been on his birthday, with a garland

of medlar leaves.

Matthijs opened his eyes again. He was horrified to discover that in response

to the feel of the sand that he had written the word ‘Eline’.

He continued to stare at the strangeness of it. Had he really done that?

Suddenly he rubbed out the word, when he heard the excited voices of the

fishermen. They are coming! They had discovered it.” (pages 47-48, 1992 edition, Querido Publishing, Amsterdam.)

The book has an open ending; we don’t know what the fishermen discovered.

When the book came out, children were angry, while some teachers used

it to teach their pupils to make up their own ending. A year later, in

1957, I received the national children’s book prize for it. This was remarkable,

not just because I was an unknown writer, but because the setting was

in a black society.

My next book (my sixteenth), “Padu is gek” (Padu is nuts)2

was published in 1957. The main character is a black youth in a village

on Curaçao. It was my first book with a black person as the main character,

although none of my books centred on any one main character. Padu is a

young boy brought up strictly by his grandparents. He hates the macho

image that is expected of boys, and doesn’t care that he is called sissy.

He spends a lot of time by himself, playing his harmonica in a wreck on

the beach. He is told that the wreck is haunted and everyone thinks he

is crazy for not believing in ghosts. He finds a stolen baby, and is blamed

for kidnapping it.

It is a complex story, but the main theme is of bullying and not fitting

the expectations of others. I wrote this because a number of Curaçao men

told me that they found the macho culture difficult to cope with as teenagers.

When I visited the Antilles in 1958, I discovered that there was only

one person called Padu. He was a musician on Aruba, who had produced a

number of albums. When I met him, I offered my apologies, and he laughed,

saying that everyone was a bit crazy, and besides, the book had helped

promote his name. Padu was a name I remembered from my childhood; later

I found out that it is the Papiamento word for grandfather!

Some have asked how a white woman can write a book about a young black

boy. Well, all these stories came from my childhood. I believe that you

absorb so much more as a child than as an adult.

While writing these two books, I started working on the Annejet series.

This was in 1956, when comic books began to be popular, and children were

not reading books because they found them boring. My assignment was to

write a series about an ordinary Dutch family where exciting things happened,

in a language that was easy for young children. The main characters were

Annetje (who was 12 in the beginning of the series and 16 at the end)

and her 8 year old sister. Five books were first published in 1956, and

since then they have been re-edited four times with each reprint,3

to incorporate changes such as the development of television, the education

system and ballpoint pens.

Recently, Czech television produced a film based on the series. It was

important to me that the books were contemporary for the young reader.

For example, the title of the first book was originally 'Annejet stelt

zich voor' (Annejet introduces herself) and in the 1994 version it is

"Lief zijn op bevel" (Be nice on demand) where the main action is about

how Annejet adjusts to her 13 year old crippled cousin coming to live

with her family and sitting in the same class as her.

In the latest version the emphasis is on how difficult it is for her and

her cousin to cope with their emotional reactions and frustrations towards

each other - as instant 'siblings', and towards their peers. The matter

of fact language reveals Annejet's anxieties with realism.

After receiving the prize for Brakkeput my writing took a more professional

turn. The Royal Dutch Merchant Company wanted to encourage young

people to choose the marines for a career, and asked me to write a book

that showed how attractive life at sea was. They approached Anthonie van

Kampen, a famous Dutch writer of seafaring culture, and he suggested me.

I was still working full time as a journalist and just at that time, I

had written an article based on interviews with marine wives. The article

got me the assignment. They wanted to send me to Hamburg (one of the largest

harbours in Europe), but I argued that the sea was something that connected

continents, and suggested the Dutch Antilles, a place only accessible

by boat and where there was an abundance of ships and boats. After twenty

years, I was now able to return and give something back. The resulting

book, “Driemaal is scheepsrecht” (‘third is ship’s right’ or ‘third

time lucky’), was more journalism than fiction. This was what they wanted

and I didn’t see a problem with it, although the book surprised the critics.

For me, it was just like working for the newspaper, except that I was

now on the sea. I chose a saying for the title because the Dutch language

is full of sayings that relate to the sea. Most of these come from the

1600 - 1700’s, when we were a great naval power. Many of the stories -most

true- describe the sea as the important means of contact that it is for

these islanders.

I returned to Curaçao in 1958 as someone who had had some contact with

some families and who had written about the island. I wanted to find out

more about the black society, but was bombarded with invitations to parties

and expected to mix with the elite. However, when I arrived, I was met

by a Curaçao writer, Sonia Garmers, who became one of my closest friends.

We were able to help each other in our writing. Some of her books were

published in the Netherlands and she told me things about life there that

I, as a white person, would never have known, or could not have written

about with such directness, without her help. We trusted each other so

much that we could have arguments! Something unthinkable between a black

and a white person in those days. Some people have commented on all the

things I did for Sonia, but without her I would never have had access

to the native culture on Curaçao, and could never have written the books

that I did.

|

Left to Right:

Left to Right:

Sonia Garmers-Melendez,

Miep Diekmann

and Henk Dennert

from the CCC

(Cultural Centre Curaçao),

meet in Curaçao

in 1958. |

Sonia’s grandmother lived with her family, and still had the certificate

that released her from slavery as a child. She refused to speak to white

people, only spoke Papiamento, and yet approved of my presence in the

house and of my friendship with her granddaughter. I still cherish the

indescribable moments when we shared a cigarette and she took my hand

in hers. These are moments I couldn’t write about, but they have had a

great impact on my life.

1

Available in: English, Methuen & Co. Ltd, London, U.K., 1959, as "The

Haunted Island"; French, Bourrelier, France, 1961; Africaans, Tafelberg

Publishing, South Africa, 1961; re-translated into English for Dutton,

U.S.A., 1961; Czech, Albatros, the Czech Republic, 1969; Russian, BeceHka,

Kiev, The Ukraine,1988; in Ukranian,Weselka Publishing, Kiev, The Ukraine.,

1988.

2

Available in: German,Westermann Verlag, 1960;

3

Available in: German, Engelbert Verlag, 1966/67 & 1974; Czech, Lidové

nakladatelstvï, 1972, & Mladá Fronta, 1978;

Excerpts

from Arts Dialogue, September 1997, pages 6 - 8.

|

|

Part Two

In this interview Miep Diekman focuses on her coaching writers from

Curaçao and Aruba, and her novel set in the Dutch slave trade.

When I was in Curacao for those few months in 1958 doing the research

for the book, "Driemaal is scheepsrecht" ('third is ship's right'

or 'third time lucky'), the StiCUSA (The Society for Cultural Co-operation,

the Netherlands and the Dutch Antilles.) gave me a daily allowance to

give lectures and workshops in schools. I was asked because "De Boten

van Brakkeput" and " Padu is gek" were the first books that

dealt in any depth with children from the Dutch Antilles.

|

While I was

there the Antilles Government asked me to write a series of books for

use in their schools, because the teachers were not happy with the materials

they had. Some friars in the Catholic schools were so excited about this

that they sent me a list illustrating particular difficulties that the

children had with Dutch. I waited until 1961 before beginning on this,

hoping that someone local would take this on. The settings are on each

of the three islands because the children didn't know much about the other

islands and so each story has something typical for that island. For example

on Aruba most of the inhabitants descend from Indians. The books first

came out in colour in the Antilles and then my publisher in the Netherlands

also printed them. "Nildo en de maan"1

(see

notes on right).set in Curacao came out in 1963 and was written for 4/5 year olds. Jossy

wordt een Indiaan 2 (Jossy becomes

an Indian) was set in Aruba and for the next class.

Shon Karko 3 (Master Kinkhorn Shell)

was written for 6/7 year olds and was set on Boniere where many shells

are found. "Het geheim van Dakki Parasol" 4

(The secret of Dakki Parasol) was written for the next class. Dakki Parasol

was the Simon Bolivar Museum, where Bolivar and others who liberated South

America from the Spanish, lived for a time.

A prominent Curacao businessman from the Lions Club, came to the Netherlands

to ask me if one of the books I was working on for the Antilles primary

schools could be connected to the "Keep Caruacao clean and beautiful'

(Tene Korsow limpi bunita) action that they had initiated. They didn't

have much money, and they wanted to reach the young with this action,

so I thought 'why not?'.

This detective story is based around a national clean up action on Curacao,

where a group of 7 or 8 year olds are the main characters. The story begins

with a photographer attempting to get the crowd to disperse so he can

take a clear shot of the old woman, Cirila's heap of old furniture, plastic

containers, and so on. Slogan-like phrases throughout the dialogue give

the effect that everyone is involved in this action in one way or another.

"No more rubbish

on the street. No more rubbish in the kunuku -suburbs.

"

(translation from pg. 8, 1977 edition.)

are cries

as if given facts, followed by:

"...most people didn't

like the medicine. They loved their heaps of old things better"

(

ibid, pages 8 and 9)

Then the story

develops around the children who see Cirila's pile of rubbish as a treasure

trove of things. An old screw fixes Sherwin's leg brace, and then Ibi

is delighted that he can store his collection of junk, which he must remove

from his home, in her heap.

|

...De Boten

van Brakkeput and Padu is gek were the first books that

dealt in any depth with children from the Dutch Antilles.

1.

Wolters, The Netherlands, reprint in 1975, Leopold, The Netherlands,

Translated into: German, 1970, Bitter Verlag, Germany; Papiamento, 1984,

Charuba, Aruba/The Netherlands.

2. 1964, Wolters, The Netherlands, reprint in

1975, Leopold, The Netherlands. Translated into: German, 1970, Arena Verlag,

Germany; English, 1970, Abelard Schuman, England; Danish, Gyldendal, 1972;

Papiamento, 1986, Charuba, Aruba/The Netherlands.)

3.

1964, Wolters, The Netherlands, reprinted in1968, Leopold. Translated

into: German, 1969, Arena Verlag, Germany; Czech, 1979, Albatros, Czech

Republic; Papiamento, 1987, Charuba, Aruba/The Netherlands.

4.

1967, Wolters, The Netherlands, reprinted in1977, Leopold. Translated

into: German, 1972, Bitter Verlag, Germany.

|

The children often play there and one day encounter two men posing as rubbish

collecters who steal a table and stool. The children then decide to collect

old bottles and newspapers to earn money for a new leg brace for Sherwin

and while they do this over the island they are on the look out for those

two men. Then they discover that the man hide their loot in the museum Dakki

Parasol.

Each chapter,

of a few pages, is a self contained part of the whole story, with a climax

and so on, so that would be more interesting for children who would read

a chapter at a time...

The themes in the context of a national clean up action, are of children

not being believed by adults, of attachment or detachment from possessions,

on the value of things, and so on, as well as some early nineteenth history

around Simon Bolivar and the Curacao hero the black general, Piar....

The first four books came out between 1961 and 1967 and I stopped with

parts 5 and 6 when the Black Power asked me to stop, and I respected their

wishes. They wanted some local writers to take this on.

Ever

since I was 20 I had wanted to write a history of the slavery in the Antilles,

and so I spent fifteen years researching everything I could get access

to in all languages and, in museums in various countries. The journals

of ship doctors were a major source as was the journal written by the

voyager Adriaen van Berkel in 1672. This only exists in two museums in

the world, and the only way I could read it was with gloved museum attendants

to turn the pages for me.

A lot of my material about the sugar plantations in Berbice (now east

British Guyana) came from this source, where in it all the plantations,

their exact locations, their owners, the type of sicknesses, the conditions

of the slaves, etc, were described in great detail. It was a gift from

heaven. There were even drawings in it that my illustrator adapted from

for my book. All these details were vital for me, as my novel is full

of these sorts of details to give as full a picture as possible.

The huge plantations in Berbice were a contrast to the small ones on Curacao,

and in my book, there is constant reference to Berbice as a horrible place

for a slave, but the reader doesn't get any first hand experience of it

until Marijn goes there towards the end of the novel to rescue Knikkertje.

We also then realize that slavery was much harsher on the big plantations

than it was on Curacao. I believe emphatically that a lot of racist acts

and beliefs exist because people don't know the facts. That is why I researched

so much for this book. It was to be fictional, but it was important that

the events were ones that did or could have happened. It had to be accurate

and detailed enough so that it could serve as a social history.

|

The Antilles

were colonized by the slave trade from 1501 onwards and it was not abolished

until 1863. I also wanted to wait until I'd written enough to be confident

that I could write this well, because it had to be a good book. And it

was a first. There was nothing written about the history of the slave

trade in Caribbean, and I ended up using about 5% of all the information

that I had found on the subject.

In my novel, Marijn and the Lorredraaiers (Marijn and the freebooters)

5 there

are three main characters who grow up and together, in Willemstad on Curacao:

a white brother and sister, and a black girl, who are all about 14 years

old at the beginning.

|

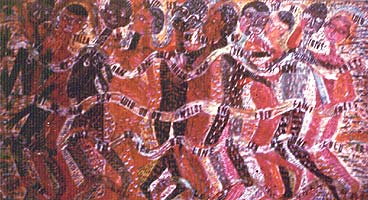

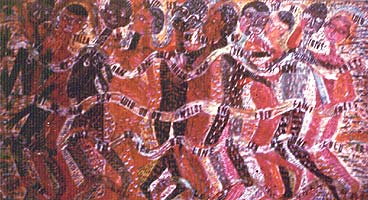

Folk dancers and singers, painting by Philip Moore, Berbice, Guyana.

5.

Translated into German, Westermann Verlag, 1967; Kinderbush Verlag,(then)

East Germany, 1971; English, Morrow, U.S.A.,1970; French, Robert Laffont,

1971; Czech, Albtros, 1971; Slovakian, Mlada Leta, 1977; Croatian, Nolit,

1985.

NB: All quotations here are translations from the Dutch edition.

|

The novel begins with Oeba's thoughts as she looks over the Willemstad

from a hill above, and of her fears of the dark and of pirates. Her brother,

Marijn, then confronts her fears with his rationale, and describes the

attempt to fix the leaking water tanks that day and tells her that a lack

of water was their real greatest fear. In the dialogue and the thoughts

of the brother and sister the reader knows -what they are wearing, the

climate, of how the buildings and harbour look, and their views of their

school friends. The details of a school friend who had recently immigrated

from Holland inform the reader of some of the differences in schooling

between the two countries, as well of the Dutch customs that have been

translocated onto this island, such as their European clothing suited

for a cooler climate. For example in the following passage, we are given

a number of facts, but they flow within the framework a dialogue between

Oeba and Marijn.

"Would you have been

frightened if in 1634 you had to take control of the island with Johan

van Walbeeck and then built the Castle with the soldiers and seamen."

"What, a handful of Spaniards,

who'd be frightened?" Marijn muttered.

"Yes but, our Fort was

just the Castle then, only of wood and with no massive gate before it.

Just a fence with wooden spikes which you could easily jump over. Must

have been lonely then. Only four wooden houses, each with a sail cloth

for a roof. Just think of the rain and the horrible wind! Only the director

of the West Indies Company had a house made out of stone...

"You've remembered your

school lessons well" retorted Marijn scornfully.

"Yuck, I hate school.

I wish it would fly away," cried Oeba earnestly.....

As he walked down the

path to the Fort, he still heard Oeba's words: the school...fly away...

He had to get to the Waterside, to look and to see if the seamen knew

anymore. (pages

14- 15)

What Marijn wanted to know from the seamen the reader can only guess at,

just as Marijn himself was only guessing. Then suddenly at the end of

chapter one, we are informed through the views of the three who are all

now standing on the hill, that a hurricane has hit Willemstad.

On the 20th of October in1681 a hurricane hit, destroying all of the waterfront,

much of the town of Willemstad, part of the adacent town, Fort Amsterdam

and swept the slave quarters on the Westwal into the sea. Many died. Now

Marijn and Oeba are orphaned and must stop school. Marijn goes to work

as a trainee to a slave doctor in Fort Amsterdam and Oeba and Knikkertje

go to live on a slave plantation with Oeba's elder sister and husband

on the other side of the island.

Carving by Philip Moore, Berbice, Guyana.

Carving by Philip Moore, Berbice, Guyana.

6.The

Caiquetio clan was related to to the Arowak-Maipure tribe who were

spread around the North part of the South American coast. Indians

were not sold into slavery, but allowed by the Company to live in

designated areas of the island.

|

"Jan Frederik has

got the job of slave doctor on the Saint Joris slave plantation,"

said Aletta. "We are going to live there."

She looked away.

"At Chinchoor?" asked Marijn with a sparkle in his eye. "On the

North coast?" He didn't notice that on hearing the Indian name for

Saint Joris, that Aletta wanted to say something. "Did you know

that there are still Caiquetio Indians 6

living on the island Makwaku in the bay of Chinchoor. There

are all sorts of stories...

"Saint Joris?" asked

Oeba. "Isn't that where they send the slaves that are brought over

from Africa, the ones that arrive at Willemstad so sick that they

have to go to a slave plantation first to be nursed back to health?"

She bit her lip. So Jan Frederik wanted to go and work with the

slaves? She didn't know whether she considered that praiseworthy

of him or not. As the slaves got better, they were sent to the dreadful

plantations in the Caribbean from which none of them ever came back

alive. So Jan Frederik would do better to leave them sick. But what

was a doctor for?" (pages 46 - 47)

|

Here the reader

can see that the slave trade was so dominant that even improving the health

of slaves was contributing towards it. The slave trade was the result

of economics, not racism per se. The multinationals such as the Dutch

West Indies Company were interested in making money, not in people. That

was just as awful, as racism grew out of this -the Africans were treated

as goods.

As a doctor

on a pirate ship, Marijn hears of how a sailor particularly hated the

slaves because on a Company boat when the food ran out, it was the sailors

who starved. On the pirate boat the crew is given much better treatment

but the slaves are not. They were treated as goods, to be kept alive until

sold.

I chose the

17th century term for the title, because these 'free ships' while working

as slave ships were, were independent of the multi-nationals. The implication

of the word is that they are pinching something (from the multinationals).

All the official harbours were banned to them so they (and the pirate

boats) had to live by their wits, creating connections and stopping at

smaller harbours. Curacao had many natural harbours so it was particularly

vulnerable to pirates and to any ship. This is mentioned in the first

paragraph in the thoughts of Oeba while she gazes across the harbour.

Curacao's wealth depended on the trade of the freebooter, privateer and

pirate ships who couldn't stop so easily elsewhere in the Caribbean. Because

they had to stop at smaller ports along the North-east African coast,

they tended to get the sicker or weaker slaves and so a doctor on such

a ship was more vital.

When the slaves

were bought, the doctor had to check the slaves for their relative health,

and this process along with the tricks the sellers did such as dying their

hair, is detailed in the book. If too many slaves died enroute, then -and

it really happened- a doctor was thrown overboard. The income from the

slaves was divided among the crew, and this was also cause for resentment

amongst the crew, whose lives and income depended on the health of the

slaves. The hardness of sea life for slave and seaman alike was complicated

by the pirateers. They were ships with permission to hunt other ships

from countries at war (and the Dutch ships in particular gained much of

their wealth this way) such as the Spanish or the English, and lawfully

take their ship and their cargo. But if a treaty had been signed and they

didn't know this, then they were outlaws.

I use alternating

viewpoints throughout the book, and this is a typical of the way I write.

When this was being translated into English, the publisher wanted to change

this. I disagreed. I didn't want it to be an adventure book, with the

boy as the main character. Each of the three viewpoints were important:

Marijn's mixed feelings for Knikkertje and of his decision to join a pirate's

ship as their doctor to escape this delimma, of his adventures on Cuba,

then on the freebooter slave ship, and then his resolution to free and

marry Knikkertje.

Oeba's thoughts

as a young woman expected by others to be protected, of her rebelliousness,

of nursing the slaves, and of her love for Knikkertje.

Knikkertje's views were important, because they provided an insight of

someone who was brought up like Oeba, but who was black. And in those

days, there were slaves who were brought up as Knikkertje was, by Humanists

and by the old Jewish families.

Later the differences

between the two illustrate the effects of slavery on two young women,

who in the beginning were very similiar in their behaviour. It amazes

me that while women did so much of the work in the Netherlands (and on

Curacao) because the men were away at sea, that so few books mentioned

women at all. In the beginning of the novel the three teenagers, have

fierce arguments with each other, and equally share differing opinions

and ideas with each other. After the hurricane, each one's thoughts are

only known to the reader, except for Knikkertje. Now her thoughts are

unknown, except in snatches. We only know that she is working hard in

the kitchen and in the laundry and no longer speaks so freely with Oeba.

In the days after the hurricane, when she and Oeba were cleaning up the

rubble in the school house and Knikkertje blew into a conch shell to cheer

up Oeba.

" A long drawn-out melancholy

sound filled the whole school and floated through the broken windows and

doorway, out through Fort Amsterdam ....

The sailors of the island blew on conch shells to awaken the spirits of

the air when there was no wind. The spirits aroused by the tones, blew

onto the sails of the ships pushed the ships out of the blue waves....

Over her rosy conch horn, Knikkertje looked at Oeba, whom she loved above

everyone else. Oeba was grief stricken, but hid it from everyone. Big

tears spilled out of Knikkertje's eyes, down her cheeks, and over the

pink enamel of the shell.

She didn't see Marijn standing outside the window listening. She didn't

notice that behind Marijn others had gathered to listen. People who had

dropped their work in the fortress on hearing those melancholic sounds.

Knikkertje only saw Oeba and Oeba's eyes that were sparkling as they used

to. And she only felt Oeba, close next to her and not distantly as it

had been in the last days...

But her happiness didn't last long. Suddenly a man stomped into the school.

With a whack he knocked the shell out of her hands.... p

37-8

That man was

the jailer who then put Knikkertje in jail, despite Marijn's claim that

she was their slave. She only just escaped being sold off to a plantation.

Now she is more cautious, aware that while she is not quite in the world

of the slaves as someone who could read and write, she was not safe in

the white world either. Near the end of the novel, Marijn noticed that,

"She addressed him as slave

always spoke to her master, in the third person. She was free now, but

her words, told him how little freedom she felt."(page 313)

...Like in a

film, I used flashbacks to provide details while retaining the pace of

the story such as with Oeba's thoughts here.

As always when she entered

that dusky room, she had to pause for a moment. She then had to try hard

to recognize faces among all those black gleaming patches lying just off

the ground. Human faces.

That was the first lesson Jan Frederik had taught her. "If you want to

work here, to really work and accomplish something," he had said earnestly,

"never let yourself forget that you are working with human beings who

also suffer pain and grief, even though they are only considered as goods

by most of our people." p.

73

...I would imagine

that a boy would identify with Marijn, a girl with Oeba and an African

descendent with Knikkertje. That was also an important reason for choosing

these three as the main characters. When I started on the book it was

hard to know how to deal with the gruesome value system. How to make it

readable and still realistic. Then a man's hand could be cut off for a

crime, while a slave's was never cut off, because his was worth too much.

Then I discovered a way to put this in a context. The Dutch West Indies

Company that ran the slave trade, that dominated the way everyone lived

in that area, was a multinational. Everything fell into place. The value

system was based on economic gain.

|

"Are

they ill from disease or from the voyage?" she asked business-like, and

with a face as if she was the boss herself.

"The skipper stowed his

hold much too full. The slaves weren't allowed on deck, because there

were pirates in the vicinity and fighting could have broken out. You can

image the rest." Marijn pressed his lips together.

"Many suffocated in the hold."

"We must do something.

Now if we wrote a book about these crimes like Dampier 7

did," suggested Oeba.

"Most people cannot read,"

answered Marijn scornfuly.

"And those that

can read, and have money to buy a book, also have money to deal in the

slave trade. Look at the rich men in Holland. They have never seen a slave

or a slave ship, nor participated in an auction. But they invest their

money in the slave trade and say that it is a Christian deed, because

everyone does it."

"But we have no part

in this," cried Oeba furiously.

"We do have a part as

long as we are in the service of the Company," said Marijn. "That is a

straight fact, and you can't deny it....

|

7.

The Englishman William Damper wrote two books about his travels and

of life at sea. At the back of the book I included over a 100 terms or references

such as this one where the reader could find out more about who Damper was

and what he did.

|

...They stood facing

each other, and so didn't notice the cloud dust that was approaching through

the barren, forsaken landscape. Nor the stranger on the horse... excerpts

pages 78-9

We

read about how the best slaves were selected and how they are bargained

over between the African sellers and the slavers. How did this all start?

When the Dutch ships sailed out towards the Caribbean they followed the

current out and stopped along the north-east African coast. They needed

people accustomed to a hot climate to work on the plantations in the Caribbean

since the Indians escaped into the forests, whenever they had tried to

capture them. Along that coast there was constant fighting amongst the

tribes and the law was that the winner had to feed, clothe and take all

the members of the tribe that had lost, into their own army. When there

were too many, they were killed. The traders offered to buy them since

they would be killed otherwise. So the slave trade didn't begin as an

evil deed, but what happened was that the warlords then began to raid

villages to supply the traders with slaves and then the injustices grew.

We can identify with Marijn's dilemma as he examines the slaves, those

chosen wouldn't have great life if they survived the journey, and those

not chosen were thrown to the crocodiles.

Another

problem I had with the English translation, which is roughly half the

size of the Dutch version, was the scene where Oeba forces Knikkertje

to put her own party dress at her 15th birthday party, which shocks Oeba's

prospective husband Floris, and the guests, and results in having Knikkertje

moved to the slave quarters.

Another

problem I had with the English translation, which is roughly half the

size of the Dutch version, was the scene where Oeba forces Knikkertje

to put her own party dress at her 15th birthday party, which shocks Oeba's

prospective husband Floris, and the guests, and results in having Knikkertje

moved to the slave quarters.

Here

Oeba's desire to share with Knikkertje is so strong that it does harm,

but it is also illustrates the deepness of prejudice. Here Knikkertje

was the belle of the ball, and Floris's reaction was to scream in horror.

For me this is the crucial point of the story. Knikkertje is in Oeba's

dress, but she is not the same as Oeba.

The

publisher had already said that the book had to be much smaller to fit

into a series, and I was happy about editing it myself (a whole chapter

about the Indians and their relationship with the slaves is omitted) as

I had done the same with the French version.

But now the publisher said that this part had to come out. This was in

1970 and I had just been in Curacao and had been involved with the Black

Power there, so I was sensitive about these issues and said no. Then publisher

said that they had an African American editor who agreed that it should

come out. I felt this was discrimination, so I said that I would cancel

the contact if this part was omitted. It was printed but it didn't sell

very well. Then I was at a writer's conference and told my story of how

difficult this publisher had been about my book, and some librarians from

America came to complain that they had never received the book. So on

their return they wrote an article against the publisher which also promoted

my book. Now this book is in its 8th reprint and while classified as a

book for teenagers in the Netherlands, it is treated as a text book for

all ages on Curacao.

This relates to the theme in my book about the slave trade too. If something

goes wrong it is due to something being wrong with the way the economics

of a society is set up. During the slave trade multinationals governed

the ethics and functioning of a society.

|

image to come...

|

Part Three

In this interview Miep Diekman discusses her two books, Een doekje voor het bloeden

(A cloth for the blood), Leopold Publishing, 1970, and De dagen van Olim

(The days of Olim), Leopold Publishing, 1971.

In May 1969 there was rioting in Willemstad, the capital of Curaçao. On television in the Netherlands, we saw buildings on fire and people looting.

In response a number of students from Curacao demonstrated outside the Curaçao embassy in The Hague. When their parents saw this on television back home, they cried "Oh my God, my child has become a communist." The students were protesting against the inequalities in Curaçao, created in part by the multinational company, Shell. Many people on the island were dependent on an income from Shell. But in those times in most western countries, any sort of a deviation from the norm was stereotyped as being communist.

This relates to the theme in my book about the slave trade too. If something goes wrong it is due to something being wrong with the way the economics of a society is set up. During the slave trade multinationals governed the ethics and functioning of a society.

|

In the Netherlands there was a lot of misinformation and a lack of information about the situation in Curaçao, so I wrote a non-fiction book about what was happening. Een doekje voor het bloeden (A cloth for the blood)1 starts with the thoughts and feelings of a black family of seven, who are in the Netherlands for a long holiday. We read how the father is surprised at the directness of the television broadcasts; how a Dutch farmer was surprised that the family members were different shades of brown. There are interviews with members of the Black Power as well as the opinions of the older generation who wanted things to go back to what they had been. I wanted to show that the situation was complicated. To illustrate the cultural differences as much as the injustices, injustices that didn’t come from one source but were imbedded in all aspects of life, from the colonial days to the 1970s, when Shell controlled the economy...

|

When the Black Power said that they wanted their own

people to write books for their schools, I got the idea to coach their writers.

I did this on a voluntary basis. My travel was covered by my publisher and

I stayed with my friend and fellow writer Sonia Garmers and her family.

When I arrived in Curaçao in October 1969 journalists, writers and poets

came to the first meeting, where I offered to help any writer with their

use of Dutch and the technical aspects of writing. Some were afraid that

I was out steal their ideas and so in the end I coached only two writers,

Diana Lecas and Sonia Garmers, who both went on to publish numerous children’s

books. During these 3 months I also had an intensive programme where I gave

lectures and workshops on the Dutch Antilles...

|

Miep Diekmann with Angel Salsbach one of the Black Power leaders, a Jazz musician and an engineer, who is now a government official in Curaçao.

|

De dagen van Olim (The days of Olim)

In my late twenties I ended up in hospital with severe paralysis that appeared to be an affect of an accident I had when I was 14. I had fallen from the roof of our house in Willemstad. The neurologist guessed there was more to the incident and referred me to a psychiatrist and for the first time I started to deal with my childhood and the accident.

I had had a strict upbringing. Being presentable in the colonial white society was important as the eldest daughter of the head of the military police on the island.

One of my first memories after our move to Curaçao was when my sister asked why the taxi driver´s

hands were white on the palms. I thought to my nine year old self "now this will be interesting," but

my parents didn't say a word. That made a deep impression on me and in reaction to the silences when

it came to black and white interactions, I always tried to find an answer, rather than bear with the

silence. Discrimination often happens because of not knowing what to do or what to say.

There were tensions in the house between my parents, tensions due our strict upbringing, an attempted rape and then my accident. The psychiatrist advised me never to return to the Antilles.

When I visited the old house in Willemstad in 1958 for the first time, I realised the fall from the roof wasn’t an accident, that I’d actually dived off, just as my sister had said. It shocked me. It was awful. I had a terrible headache from reliving the whole thing. Standing there then I realised the meaning of the recurring dream I’d had beforehand. I was falling. The fall was a dive where the stones were coming towards me. Then the stones turned into water and I dived into the water and swam away free. That dream had saved my life. If I hadn’t dived with my hands forward, I would have broken my neck.

I was in a coma for 10 days. Coming in and out of the coma was fearful. I could hear but not react. Everyone around me thought I would die. The fear of being sent to an lunatic asylum hung over me as I fought with memory loss and relearning to mobilize my limbs. Since then my life has been full of headaches, backaches, periods of hospitalization and sometimes loss of memory.

Later when I spoke with my psychiatrist he told me that he knew that it had been a suicide attempt but thought it too risky to tell me. The famous Antillen writer Cola Debrot (governor of the Dutch Antilles: 1962-70) encouraged me to write a book about this.

Five years later my only autobiographical book, De Dagen van Olim (1971, Leopold Publishing) was published. This was a year after I had received the national literature prize for my ouvre, but it was a struggle to get this book into the libraries. A suicide attempt was considered an inappropriate theme for this age group. I was told that children didn’t have these feelings and that I’d made it all up to sell the book. But many children since then have identified with the feelings expressed in the book and have been relieved to discover that they were not alone. Since then the book has been reprinted six times.

The novel, The days of Olim, begins with main character, 14 year old Josje, angry at a classmate of hers. The head nun in the school has been told that Josje had been caught in a bathing shed with a boy. She runs out of the classroom, knowing this is not true but not wanting to get the other girl into trouble. On the way home she just manages to escape a ride with an uncle who always tries to put his hands up her dress. Once home the reader hears of the meaning of the novel’s title. The days of Olim, Latin for long ago, was a phrase her father used for ‘in the good old days’ and here these are connected with the mythical existence of a brother that would never have done wrong. The head of police only had three daughters.

There had been a brother, otherwise how could her father look at her and her sisters with those cold eyes, those tense cheeks, and say;'Girls'.

Why must they never cry? Why was he proud if her pace was faster than the sons of his deputy...

...In the days of Olim everyone solved their own problems. No crying to mummy or daddy"

(page 9)(translation from Dutch by Sonja van Kerkhoff)

At the end of the novel the title seems particularly apt, given the tragedies that have happened. As a reader you are encouraged to question how to judge about what was ‘good’ and what was ‘bad’ in the days of this girl’s youth.

The only times that Josje’s father gave her much attention were when they are playing rough but then "If you didn’t watch out you’d fall when he suddenly let you go. Then he would brush off his hands against his uniform. Never trying to hide this from her, certain that she didn’t notice. Just as if hehad touched something dirty." (page 9)

... Jos turned towards her mother who without further a-do stepped straight into the house. Hadn’t she thought about what she was doing...

‘You don’t do that in Holland do you? First almost run someone’s dog over, and then walk direct into their house to film it for your family overseas. If that woman took a fly swap and hit you with it. She would have justification.’ But the woman wouldn’t grab a fly swat. Instead she’d feel ashamed of the untidiness in the house and that there was no furniture like the whites had. Shame because her children played naked outside. "You should throw her out. You should say: this is my house. You could have first asked nicely if you could enter her house," grumbled Josje to herself.

But the woman would only stand and laugh, an acquired laugh of gratitude for receiving so much honour

... all the way home in the car, Josje puzzled over: how can you teach a woman that she must say ‘no’. (p. 80-82)

Later in her fury Josje throws a book about polite girls getting engaged to upright boys. The book knocks a photo from a pile on her father’s desk. It is a young black man who -rejected by his girlfriend- had thrown kerosine over himself and is severely burnt. The contrast with the book she had been reading, a romance in a fantasy world, couldn’t be stronger.

As a reader, you realise that it is hard for Josje to be a child when she is aware of some of the police cases her father is dealing with and aware of the injustices going on around her. Later she and Bubi, the boy she is fond of, overhear a case about a girl being locked in a shed for years by her father for walking with a boy along the beach.

"Jossie" Bubi shook her on her shoulder. "Do you often hear these awful stories?"

"They aren’t stories. They are the plague and you get used to them. It’s just, well, it’s part of life, my father says. People are like that."

"Aren’t you ever frightened? I mean you are a girl."

"What does that have to do with it?" she retorted abruptly. (p. 121)

It gets worse for her when she is almost raped by Lieutenant Lang. But what drove her to desperation was not being believed by her father, and worse, that the same man had the task of keeping watch over her and her sisters. Her dream, the dream of diving in the air and onto the stones which turn into water returns. She remembers telling her father of the dream at breakfast. His reaction was to ban her from going onto the roof. The climax of the story is when she locks the Lieutenant who is chasing her into the attic and climbs onto the roof. He gets out and to escape him she dives off the roof.

In a language that evocatively expresses Josje’s drifts of semi-consciousness we read of her gradual recovery, her fears of being sent to an institute which drives her to learn how to walk, to read, and to return to her old school. The rest of this part of the story is consumed with her struggle to survive. There is no more mention of boys or parties.

She didn’t try to find out if things had happened, were happening or were going to happen. It was like swimming in deep water without banks, and without a place to rest with your feet. Daytime was as bad as nightime.

There were a few things that she knew for sure were different from earlier....

At home it had become quiet. No loud voices, no slammed doors. However all the attention of her father and her mother focused on her, didn’t distract her from the realization that there was a cold war between them: a competition in ignoring each other. (p. 155)

Excerpts from Arts Dialogue, December 1998, pages 5 - 7.

The last part of the novel deals with Josje’s return to Curaçao twenty years later where she both deals with the past and enjoins the present. She meets old friends, and two sons of that same Lieutenant , one black and the other white. She meets with the Black Power, and with mariners sent over to keep order. The dialogues with people give the reader an impression of the changing times.

My time in Curaçao was an intensive time. It was during my puberty, and there was so much change. Here was a language I didn’t understand and we’d never seen black people before, and here everyone was black, yet my father was a VIP and all the whites were ‘important’. I found black people exciting and wanted to find out how it felt to be black. Father had three daughters and taught us that a girl could do what a boy could. He taught us to be assertive and to solve our own problems. Two of us had to train with the military in case we were attacked. With one coup after the other in South America at the time, the family of the head of the Police on Curaçao was always vulnerable. I could fight as well as any of the boys of my age. Years later I met a huge black man who remembered being beaten up by me as a child. What had impressed him wasn’t that I was a girl but that white children could fight like black children. That made them the same in his eyes. Until then he’d only seen white children look past him as if he didn’t exist.

Excerpts from Arts Dialogue, December 1998, page 10.

Part Four

Miep Diekmann talks about her book, Total Loss, weetje wel (translation, Total Loss, you know),

published by Querido Publishing, 1973 and the two books, Hoe Schilder, Hoe Wilder, (translation: The more picturesque, the more clownesque) set in Leiden and Haarlem during the Dutch Golden Age of painting in 17th century.

My inspiration for Total Loss, weetje wel came, in the first instance, from being a mother of teenagers in

the late '60s and giving lectures to teenagers in schools in the Netherlands. I was a well-known

author in this country for using colloquial language and addressing contemporary issues in my books.

The Flower Power or Hippy movement was in full swing and I decided to focus on the pros and cons of

being raised in a hippy lifestyle.

I began with the theme of individualism, not following along in the group, as my starting point for

the story, not only to illustrate the hippy and non-hippy lifestyles but also to reflect the realities

of puberty....

|

...The plot thickens when a 16-year-old terrorises all the children in Katja's street and,

in order to avoid this, many of the children join Edgar's gang. Katja refuses to join and

is then harassed by Edgar. Katja assumes that Total Loss's reaction to the situation will

be to fight, but Total Loss has been raised as a pacifist and his first reaction is to

observe. Now the problem in the story is how do these two friends solve the problem of the

bully and his knife. Total Loss's parents are half-way across the world but he still has

Herman, the hippy teacher, who he can consult, while Katja can't discuss the situation with

her parents. Herman takes them to the bully's house to talk the problem through, but the

bully grabs the knife back and cuts Herman's hand in the process. It seems that a pacifist

approach is not going to work. The conflict escalates when the bully forces Katja into a

film theatre and Katja's father, with Total Loss's help, apprehends the bully.

Unfortunately, the newspaper carries a story about how the police beat up an innocent

16-year-old, so Katja's father's reaction, one of violence to protect, does not work either.

In the end, the problem is solved by Herman's girlfriend, Helena, who uses her charms -

not violence - to appeal to the bully's ego, and now he is no longer interested in

terrorising a 13-year-old girl.

|

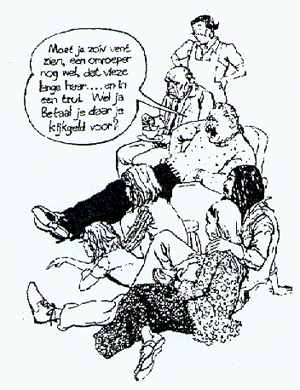

Illustration in

Total Loss, weetje wel

by The Tjong Khing.

|

...This was the first book of fiction in the Netherlands to be centred in

the hippy culture, and when it came out, I got a lot of criticism. The right

hated it. The Christian Democrats hated it because of the direct language

teenagers and hippies used, such as the term Zeikmeid (pisshead).

And the left hated it because the story revealed that they were just as

autocratic as the lifestyle they were protesting against, such as when Total

Loss is forced to lie in a coffin during a protest. I also had just changed

to another publisher, Querido, so it was a risk for them as well. My greatest

concern was to find a good illustrator for the book. I didn't want the children

to be too cute or too much as caricature. I saw the cartoon illustrations

by The Tjong Khing, who had just won a prize in Paris. His drawings were

the only ones around in which women were portrayed as equally as males,

and so I asked him to make the illustrations. He was from this generation,

so he knew how to capture the atmosphere perfectly...

The book was a hit, especially in schools in the larger cities, because

the children recognised the issues in the story and so many events were

adaptions of ones that actually had taken place, such as the protest against

cars, in which a child lay in a coffin. That took place here in my neighbourhood.

The Foundation for Literature in Community brought writers into schools.

So I was constantly giving talks in schools and universities and this book

was always brought up by the students...

|

|

Typically Dutch

Foreigners often see our 17th century (our Golden Age) paintings as being typical of Dutch culture. For the books, Hoe Schilder, Hoe Wilder (translation: The more picturesque, the more clownesque) I worked closely with my daughter-in-law, Marlieke van Wersch, an art historian in 17th century

painting. She did much of the research, while I wrote the story. The title of the two books, one set

in Leiden in 1638 and the other in Haarlem in 1639, was an expression I came across in a 17th century

overview of painters and paintings...

So in the early 1980s, I proposed this to my publisher, who agreed that there was no book

around that covered this time from this angle. But we knew it would take years to realise

because of all the research that would be required. Then began the battle with my daughter-in-law,

who had lists and lists of artists she wanted to include in the book. She would give me, say,

five pages of research and from that I would write 30 or so pages. But then she would want to

add in, say, three more painters in that part. I pointed out that it would be better to just

take a few painters and to develop a story around these, along with some historical references.

She chose the illustrations and did a lot of work getting permission from the owners to use them

in the book...

Excerpts from Arts Dialogue, September 1999, pages 5 - 10. |

Part Five

Miep Diekmann and Dagmar Hilanova receiving a Dutch Literature prize (Griffeluitreiking) in 1981 for their book, "Ik heb geen naam" (I have no name). |

The following interview considers her work in facilitating the publication in the Netherlands of about 20 books by Czech writers, and about ten of her own books published in Prague during the Cold War (1960s until 1988).

MD: In 1964 I was in West Germany to receive the literature prize for youth for my book "...Und viele Grüsse von Wancho". Then I was invited to attend writer's conferences such as the important conference in Mainau, Switzerland (near Lake Constance) attended by a large number of writers from the West and East in 1966. Here I met Czech writers for the first time. We agreed that we all knew too little about what happened on each side of the Iron Curtain. I also noticed that it was the Russian authors who were always recommended for publishing or for attention and never authors from countries such as East Germany or Czechoslovakia.

It was easy to socialise, especially when I found out that those from the East Block had no money to even buy a cup of coffee or to go to the toilet, and here I was with an allowance from my newspaper. So I got to know the Czech delegation of writers. I also knew that there was a Dutch to Czech translator in Prague: Olga Krijtová, a lecturer in Dutch literature at the Karl University. She had translated a number of books by reknown Flemish and Dutch authors and had presented one of my books to the publishing House, "Albatros," who had rejected it. As it happened I met the Chief Editor of "Albatros" at this conference, and in conversation with him I mentioned that his publishing house had a refused a book of mine. I found that he didn't know anything about this, and one thing led to another.

|

Since my main goal was to maintain contact with my fellow writers in Czechoslovakia, I agreed to be paid in Czech currency, which meant that I had to visit the country to spend this money. So in 1966 I had a contract for the publication of my book, "De Boten van Brakkeput" and my first visit to Prague. This was a conscious choice on their part because it was a story set in the Caribbean that exposed children to a world apart from Castro's Cuba. In those few years there was a lot of freedom and conferences and so it was possible to work on exchanging books for publication about how youth really lived in countries divided by the Iron Curtain. How was it, to be in love there, or about adolescent-parent relationships and so on.

|

I made most of my contacts with authors through Olga Krijtová who is married to the Dutchman Hans Krijt. He worked for me as a translator after losing his job as a filmmaker. Many filmmakers lost their jobs after the Soviet invasion in 1968, so I told Hans that I'd make him a translator!

He had ended up in Prague after fleeing the Netherlands in 1947 to avoid being drafted to fight in Indonesia. At first he worked as a farmhand and then got a Czechoslovak bursary to study film in Prague. In those days if you fled the draft, you automatically lost your Dutch citizenship. However he had retained links with his home country and it was he who contacted the Dutch Press when the Russian tanks entered in 1968. He also had good contact with the Dutch embassy who gave him a Dutch passport so he could help get the Dutch tourists out of Czechoslovakia.

|

Detail of an illustration from the book, Krik, de prins die trouwen moest (Krik, the prince who must marry), 1989

(here from the 2nd Edition 1998).

Drawing by Thé Tjong-Khing, The Netherlands.

|

|

Hans would make the translation, sticking as literally to the Czech as possible, and I then changed into contemporary readable Dutch. His Dutch was not current with the language for youth in the '60's and '70's, and, for example, in Czech they use a lot of diminutives, which in Dutch would make the text far too sentimental.

I also worked from the writer's original text, not the one that had been censored for publication, so the Dutch translations of their stories were often closer to the author's original stories than the ones published in Czech. It was rewarding for the author to know that somewhere in the world their stories were published for youth as they had intended them to be. At the time the Dutch press expressed surprise at books such as "Eerlijk Spel" (Fair Game) by Stanislav Rudolf, "De jongen die durfde" (The boy who dared) by Jan Prochazka, or "Zwijgen tot je barst" (Silence till you burst) by Josef Boucek, coming from writers living in a communist system. Of course the press didn't realise that these books were not translations of what had actually been published in Czechoslovakia. In fact I was considered a communist by the Dutch press because I was allowed to enter Czechoslovakia yearly, except for 1970 when I was refused entry at the border.

Generally I visited after the summer for three to four weeks to work on translations for books to be published in the Netherlands. I worked with the publisher of children's books, "Albatros" and with "Mlada Fronta" (The Young Front, which brought out a good magazine about culture and was aimed for a readership aged 13 - 17 years). These two publishers translated books of mine into Czech, and I generally took books from "Mlada Fronta" to be published in the Netherlands.

After 1968 the director of "Albatros" was considered a dissident, and there were a lot more restrictions. I met with authors and often carried messages from the west. I had to be very well prepared because it was too dangerous to carry anything on me that had not been approved. With the publishers we only spoke business, and what we said had to be relayed to the police. Important messages were only passed through other people, and in public places. I made it a point to buy expensive items in elite shops in the company of various men, so that people could laugh at the materialist westerner and not guess which of the men was my contact. I was always prepared with a story should we be discovered, and as you can imagine it was an exotic lover's story! This was also a protection for all the others so they knew not to do anything to help me, should we be arrested. I knew that at worst I would just be thrown out of the country whereas they would suffer far worse.

No one in the Netherlands knew that I was transferring information, mostly relating to the writer's own work, or news about writers. Still this was a great risk because many of these authors were considered dissident. In 1972 I took a manuscript into the west but that was the only time I took such a great risk. Otherwise, I always memorised the information.

I also smuggled in money for the authors on behalf of P.E.N. and Writers in Prison (a fund for those imprisoned solely because of their writing), because many writers not only had no source of income now, but their children were also banned from state higher education and so on. I never considered meeting any of the famous Czech writers such as Havel or Evan Klima, because that would have drawn attention to myself. My role was to act as a courier to help my fellow writers, who never knew who brought the money. However for them the financial aspect was not as important as the exchange of ideas. And it meant that, even during the communist times, when things had to be done in secret and underground printing cost a lot, the writing culture was still alive and able to surface in 1989.

I had a code with my sister who worked in the police. I would ring to let her know that my back was fine etc, and she then rang my contact from the Dutch P.E.N. who later, typed over my reports on their own typewriter for the P.E.N. headquarters in London. This was so that no one could find out who the source of the news was. I was extremely careful with all my contacts in Czechoslovakia and in the Netherlands, and I think that is why I was able to continue helping the Czech writers for so many years.

|

|

Some acquaintances of mine even thought that I must work for the Czech police because I could enter the country and travel without any restrictions. In fact there were times when my Czech contact thought this about me and I thought the same about him.

It made me realise how a Cold War creates such distrust in people. And this is the major theme in "Krik de prins die trouwen moest" (Krik, the prince who must marry). I couldn't have written this book without my twenty years of experience in working with and around the system, in Czechoslovakia and in the West.