BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Sandy Hoover

music producer, musician, vocalist, + Lunar Drive bandmember,

UK / U.S.A.

|

Music CD,

Here at Black Mesa Arizona

list of tracks

Vocals: John B. Benally, Sandy Hoover, Sam Minkler, Kevin Locke, Rey Cantil, Henrik Takkenberg.

Produced by: Sandy Hoover, Count Dubulah and Dave White.

|

I write and program the music, and co-produce, for a band called Lunar Drive.

The group produces a blend of Native American music, mixed with UK dance music influences, along with a heavy dose of pop. It is based in London, Arizona, Michigan and North Dakota. Because the members live thousands of miles apart and have other projects and jobs, the group is not band-like in the usual sense of the word. However, we've managed to perform in Australia, New Zealand, Belgium and the UK, do two albums and a video. Our first album Here At Black Mesa Arizona was recorded in 1996 on Nation Records in the UK, and licensed for the US by the Beggars Banquet, NYC label.

The second album All Together Here was released in 1999 in the USA and Canada, on the Beggars Banquet label.

Our current line-up has a core of three Native American guys and myself. They are Rueben Fast Horse, Ed Walksnice and Rey Cantil. In addition, other people have contributed vocals or ideas into the mix. We have been trying to make pop dance music that has Native American elements and vocals, without sounding stereotypically melancholy or New Age.

The guys are avant-garde and creative thinkers. Rueben Fast Horse and Ed Walksnice dance and sing in traditional style as well. This is not a casual thing with them, they are accomplished performers.

Rey Cantil is not a traditional performer, he's a great beat poet and DJ and is the most anarchic in personality of all of us. We all contribute vocals to the songs. Even though I program the material and put in the parts, the guys have very strong opinions about feel and style.

|

Music CD,

All Together Here

list of tracks

Produced by Sandy Hoover, Count Dubulah and Dave White.

|

Because they are so successful in straddling two worlds, they can easily come up with vocals that match particular grooves or feel. And they can articulate what they want to communicate. There's nothing like collaboration to bring out new angles in everyone. Working with them has brought to light new ranges of color and concept.

The CD: All Together Here

The guest vocalists on All Together Here were Franklin Khan, Cindy Busher and Patsy Cassadore. Franklin is Navajo and was on the Bahá’í American NSA for many years. He's quite a fab singer and a luminous person. In his song A Great Traditional Word he talks about the meaning of a particular traditional song and then chants it. Cindy is a Bahá'í from Arizona who now lives on the Hopi reservation. She is a professional singer and once sang backup vocals for War (a famous black rock group in the 70s). She interpreted Nina Simone's tune Feeling Good in a completely different way. The reason we remade that song was that it's the only English song I'd ever heard that was singing to the sky, birds and breeze.

|

One day Franklin was commenting that many Navajo songs sing to plants, sky and animals and I was amazed and realised how our American/European songs rarely do that. We recorded Cindy and Franklin's vocals in my mother's garage. Patsy Cassadore is a famous Apache singer whose big hit in Indian music was I'm in Love with a Navajo Boy. I sampled her vocal from a vinyl record I found in a thrift store in Flagstaff and later tracked her down to get permission to use the vocal and create a new backing track.

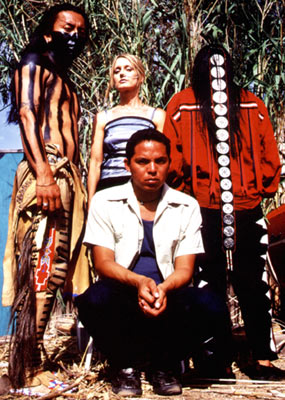

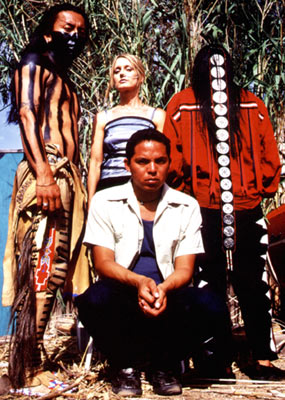

Lunar Drive: left to right: Ed Walksnice, Rueben Fast Horse, Sandy Hoover and Rey Cantil.

The working process for most of the second album is impossible to describe because it came together in bits and pieces at different times. However, for some of it the work pattern was: I made some musical or groove sketches and sent cassettes to the guys, they developed vocal ideas, and then we got together briefly in Arizona to track their vocals and work out the ideas. I took what we'd put down back to London, where it went through a series of mutations. I use a computer with sequencing software and digital audio manipulation, as well as samplers, sound modules and synthesizers. Session players added elements such as guitar, violin and trumpet. Our most famous session player was Vernon Reid. He made his mark with the band Living Colour in the late 80s and is a most versatile and original guitarist. The second stage was the production process, which involved polishing the sounds and arrangements.

It is beneficial to do this process as a co-production with other people, for the sake of objectivity and the skill they can bring. It is an odd process if you've been involved with writing the material because it's hard to know when to allow further changes to happen or when to stand your ground if there is a strong difference of opinion. The last stage is the mix-down process in the studio. Ideally you arrive at the studio with everything sorted out so that the engineer can focus on the mix. In reality, however, suddenly there are things that seem wrong and last minute rewrites and programming. This is incredibly annoying to the engineer, who just might react by cursing and chain smoking.

The CD: Here at Black Mesa, Arizona

The first album, Here at Black Mesa, Arizona, was more spontaneous, cheaper to make, and more naïve. I was in the early stages of learning and, because a lot of it was created in transit, the palette of sounds was more limited. The songs developed during a series of travels and experiences. Some of the voices and ideas on it come from actual experiences and situations at the time and were not recreated in a studio. I collected a lot of voices, songs and thoughts on DAT and video recorders along the way.

The only studio-recorded vocal on the first album was Kevin Locke's. He is a most talented human. I met Kevin in 1995 only the day before we were to perform at our first UK Womad gig. After the Womad show the group had the good fortune to attend Peter Gabriel's Recording Week at Real World Studios near Bath. There were about 70 musicians from all over the world let loose to collaborate in several studios in a green and beautiful place. There was a great moment when Peter invited us to eat lunch at his table and Kevin leaned over and introduced himself. Not knowing who Peter was, he read his name tag and said, "Ah, Peter Gabriel, where are you from, and what do you do?"

The other voices on the first album are Jon Benally and Sam Minkler. Jon Benally is a Navajo (they prefer the term Dine, pronounced dee-NAY) guy who lives in an area of the reservation that is in the midst of a land dispute - Black Mesa, Arizona. He's one of many resisters who is trying to stay on his home ground. His voice is on the first track of the album. The sung vocal is an excerpt from a peyote chant. Peyote chants are quite fast and have fabulous melodies. At that time in London the pirate stations were playing mad jungle tunes and that was the influence for the rhythm track. Sam Minkler, another Navajo, is a photographer by profession. He has a very unusual and appealing voice and way of speaking. Most of the spoken bits on the album are from Sam, from a conversation we had at my mother's place that we recorded on DAT. The sung vocals of his are also from that conversation. Someone who makes a brief vocal appearance on the album is Phil Lane, who is Lakota, and lives and works in Canada. Energetic and charismatic, he travels the world and is a founder of the Four Worlds Development Project.

|

Lunar Drive: left to right: Rey Cantil, Ed Walksnice,

Rueben Fast Horse, and Sandy Hoover

| All these songs evolved differently. For Brrds and Bugs I took a sample from a conversation with Sam Minkler discussing his theory about animal species that are being made extinct due to humanity's greed. He tied it in with the Navajo creation story. It says we are in the fifth world now, and every time people destroy a world, the plants and animals that become extinct move to the next world and start populating it. Then humanity comes along and messes it all up again. In the sample, Sam was saying that the extinct species have moved on to the next world. His voice and way of speaking was very evocative.

|

Meanwhile I'd been staying at a friend's farmhouse in France, which had a fridge with a loud, pulsating motor. It would hum and pulse in this primordial way that completely took over. I got out the DAT recorder and recorded the fridge. Back home I sampled and looped it and exaggerated some of the frequencies with EQ and filters. Then I layered it with sounds to resemble, but not imitate crickets and bugs. This became the bed to support Sam's voice. The bass line and rhythm came easily and I sampled some Choctow voices and transposed them quite low to sound inhuman. While walking back from the post office later, the melody and words that I would sing came out of the blue and I went home and put them down. "Sweet birds and bugs I'll follow you to the next world through that hole that I'll punch up through the sky past the things that spiral up high."

That song came together very quickly because there was a strong feeling to what Sam was saying and a story. So lyrically, it is very simple.

Another song that fell together easily was Crying, Looking For You. Kevin sang a traditional Lakota song which had a catchy melody. It was one of those jealous, obsessive love songs that said "I've seen you and your new boyfriend around and if I catch you I'll beat up the both of you".

I set up a groove under Kevin's vocal and a friend Henrik worked out some guitar chords to support the melody. It was starting to sound like a chorus, but needed a verse and middle 8 - standard pop song stuff. Suddenly a melody and rhythm came to me and I garbled it into the microphone, with words that were nonsense. To write lyrics that made sense I drew on a time when an ex-boyfriend refused to go away and followed me like a stalker. Somehow, after all that blew over, we managed to become friends again and he explained the weird emotions he'd gone through. I drew on those sentiments to come up with verses in English to support what Kevin was saying in Lakota, just expanding the story more. There is also a sample of a vocal from a Purcell opera in the music saying "my sweet solitude".

To me, this song is an example of getting away from the cliché of Native American music, in that it is showcasing an Indian song that is not ceremonial or sacred, but an obsessive love song - a sentiment that is universal and part of being human.

|

What fascinates me about Native American music is that it is a subculture right there in America, and that it's existed long before the Europeans got there. It's a musical tradition that has developed separately for thousands of years and has an intricacy and beauty that is unrelated to European, African or Asian music. It's odd that mainstream American culture either completely ignores it or appropriates a few images for cheesy tourist art or truck stop decor.

As to lyrics, I don't think that there was any conscious effort to give a Bahá'í slant to them. I've never liked music that tried to be convincing and educational, apart from Sesame Street songs! But for quite awhile I felt paralyzed to write anything at all because I worried that I had to put Bahá'í messages into the tunes in a literal way. Or I worried that this or that lyric might offend someone. Or maybe that anything loud or wild would be considered unseemly or something. But of course all of that is ridiculous and boiled down to funny ideas I'd accumulated. In the end you realise that you're only an individual with a limited perspective and set of experiences. Being a part of the Bahá'í world is an integral part of that. So it is from that base that I can make tracks, not as someone who has something to teach. Through collaboration, the perspective and experience space becomes bigger and wider.

|

Lunar Drive: left to right: Ed Walksnice, Sandy Hoover, Rey Cantil, and Rueben Fast Horse.

|

It is interesting that Reuben Fast Horse and Ed Walksnice also went through that process of self-censorship and feelings of responsibility to a larger community. They also arrived at the conclusion that they can only create and share something as fellow humans, not as representatives of an entire community or culture.

The experience of going to Australia and New Zealand in 1997 was quite a saga and emotionally fraught, as well as big fun. I received some lawsuit money for being hit by a car while cycling in London and spent a lot of it on flight cases and equipment and cabling for the show. Dave White, who was the mix engineer on both albums, spent months wiring and cabling. Many of the tracks were reprogrammed and arranged to make them more appropriate for live performance. At this point only Sam Minkler was able to come to Australia along with Dave, due to budget constraints. We were going to meet up with Kevin Locke and Reuben Fast Horse in New Zealand to do a couple of shows. They were there doing a traditional performance. We shipped the gear to Arizona to rehearse there with Sam before flying to Australia. But Sam was busy and we only had one hour to rehearse before getting on the plane. Sam was great on the plane. The Quantas steward was going through the safety procedures about what would happen if the plane crashed in water, and in a big voice Sam said, "I'd like to survive something like that! Did you know you can make a life jacket out of your pants by tying them around your neck?"

We got to Australia and the first show was a disaster. The sampler wasn't working and was firing out random nonsense where drums should have been. Everything went wrong and we felt lousy. The next show was the following day, on a bigger stage, and somehow we rallied and really kicked it. No doubt it was still a mess but the sounds were good, the crowd went mad and danced, and it felt brilliant. We got great reviews in the papers the next day. Everyone was asking Sam for autographs and we gave a lot of radio and TV interviews. Sam was superb with interviews. He got the point across that doing something new with traditional tunes was not destructive of tradition or culture. Culture never stands still. It never reaches equilibrium.

After a big party at the end of the Womad festival, we climbed on a bus to be at the airport at 4am and fly to Auckland. You can imagine 60 mad looking musicians all turning up at the Auckland airport, most of them hungover. They set the drug dogs on us straight away. Then we were taken to a Maaori marae (community centre/meeting house) and had a lovely welcome with lots of speeches, music and food. We slept in the wharenui (meeting house) that night, with some 70 people snoring in unison.

The next day we met up with Kevin and Reuben and arranged for a rehearsal. This consisted of hovering over a boom box in their hotel room listening to a recording of the backing tracks and trying to work out parts. At that point it became apparent that Reuben had really focused on the rehearsal tapes and knew every single cue and part. Next day we were featured artist of the day on one of the radio stations and there was a lot of build up. Then the next disaster happened. A stage hand managed to plug our gear into the wrong voltage and minutes before we were due to perform he switched the power on and everything fried. So there was this crowd building out front and we couldn't do anything. The Indian guys got out there and did some sort of unplugged show, while Dave and I kicked walls in frustration backstage. I was in a foul mood from that and ran into a friend from the band FunDaMental and we started mock Sumo wrestling. In the process he kicked me really hard and I spent the rest of the night in the First Aid tent with a massive hematoma on my leg. By this point it was all very comical really. A lot of time and effort went into repairing the equipment for the next day and we did have a second gig.

I also work with other people on the occasional remix, such as for the Tom Tom Club's CD Many Rivers To Cross for MCA 1996, Made Ya Mine by Dr Didj for Ryko, Fuji Dub by Fuji Allstars for Triple Earth Records. The term remix can mean almost anything. Usually it is reworking a track to make it work on the dance floor for a standard dance genre. It also means snipping a few elements from the original song and rewriting it as a different interpretation. The three remixes above were like this.

For Fuji Dub, Dave White and I had one day in the studio to come up with something. We were given a 30-minute live African percussion performance on multitrack tape and told to turn it into a journey. As it was a live performance, it was impossible to add anything that could loop or be tied to tempo. There was no particular key per se, but the drums do imply a key, or at least a root note. After trying many different approaches the way ahead seemed to be to add some bass parts, a drone, some texture, and then turn it into a dub, using effects, muting creatively, and playing the effects and filters and EQ as though they were instruments. This allowed us to add dynamics and mood shifts while keeping the natural build of the live performance. We then had to find a way to edit and chop the piece down from about 30 minutes to 17. It was a lot of fun because the brief was so unusual and the original material was so good...

...I can barely read music and certainly would not attempt to actually write it. Everything I do is by ear. Most of the music for ads these days is done by ear with software. The people that are good at it spend a lot of time doing sound design, creating incredible sounds and effects as opposed to writing a song or melody...

...The process begins with a video tape with SMPTE code on it. You slave your computer to it in order to place musical cues to precise times to follow the action. Once the music is completed, you mix it down to a time-coded DAT tape so that it can be locked back to picture. I've only had a few opportunities to do this sort of work, but hope to enter that field in the future...

Audio editing is quite simple. First the music is loaded into the computer either through an A/D converter, if the source material is in analog, or taken in digitally. Then it is chopped into sections and rearranged. Many of the bands above would, in a studio mix session, end up with 20 different mixes, some of it perhaps live dubs. Usually a live dub will produce some great moments but is not coherent enough to release as is. So we chop and assemble those moments into something that makes sense. Sometimes it is as simple as cutting out sections that are too long or putting a fade over an ending. Occasionally things get more complex when someone wants to add extra music or vocal to music that is already mixed.

Dave White and I co-produced Almamegretta's album Lingo, released in 1998. Almamegretta is an excellent band from Naples, Italy. They're big stars in Italy and rightly so. That was a hellish project because of the shortness of time. The band members themselves were fab. We only had one day per track to reprogram the rhythm track, add parts and arrange the songs. Then it was bang, into the studio to mix, and then straight to the cut (the mastering studio) the next day. It was nice to work in some of the top studios in London and with such lovely people.

As for some details on my background, I had piano lessons as a kid growing up in a small town in Colorado, but thwarted the training because I found it easier to play by ear than to learn to read music. I hacked around on the guitar and piano but was never proficient. In my late teens I drifted around the US with some good friends in junky cars and spent a few months at the Louis Gregory Institute in S. Carolina. I ended up on the Southern Ute Reservation in Colorado and stayed there with Bahá'í friends for several months. During that time we wandered all over the reservations in Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico.

After that I went to Puerto Rico to work for the administrative center for Bahá'í Radio. My time in Puerto Rico was like a spiritual boot camp because of the multiple difficulties and madcap experiences. It also loosened me up a bit. Puerto Ricans really know how to live large and don't need lots of money to enjoy themselves. There was always salsa and merengue music around and the people can really dance. A recurring problem was transportation. In the space of two years, I had five cars. Two of them caught fire and blew up, two died and the other one would break down on the other side of the island for no reason. As a result I did a lot of hitchiking and discovered what true hospitality was. People were consistently kind; they would go out of their way by 15 miles and offer lunch and drinks. They knew how to turn a difficult situation into a party.

After two years, I went back to the States and got my BS in Electrical Engineering. To help pay for university I was a club DJ, which kept me rooted to music. In this way I unconsciously soaked up elements of song structure and dance music. I had a boyfriend who was making music with an Atari computer and I envied him. For electives in university, I took courses in sound engineering and music theory. After college I got a job with an astrophysics company that was working on a prototype for a data instrument for NASA's Cassini mission to Saturn. In theory I had an interesting job with good pay, but I felt depressed all the time. I bought electronic music equipment and a computer and put together a small studio. From observing my ex-boyfriend I'd learned enough about the basics of creating music on the computer. After about a year the depression got to me and there were some unpleasant events at work, so I quit the job and in a burst of naivete decided to move to London.

I was fortunate to land at a studio called the Beat Factory, where Nation Records was recording bands such as Transglobal Underground, Natacha Atlas, Loop Guru and Asian Dub Foundation. The English Bahá’í Conrad Lambert produced some work there for awhile as well, back in his early days.

Since moving to London, the high points have been digital audio editing and assistant engineering for the above bands and others, touring Tunisia, playing guitar for a Tunisian pop artist, DJing at a festival in Croatia and various places in London. However, I hate to sound unglamorous, but it's been a hard slog in London. To support the studio endeavor, I have done waitressing, cleaning, receptionist and telesales jobs.

Now things are better. I'm working at a production house in Soho, assisting in laying up music for an animation series for Universal Pictures. The composers at the studio have created a music library of stings, effects and background music for the series. I help chop and fit the music to scenes and decide where to place it to enhance the visuals. It's pleasant work and the people are great. In the meantime I'm working on my own tracks and will be working with another producer doing dance remixes. If all goes well I'll be sorting out the musical cues and doing sound design for Joseph Houseal's Digital Komachi project.

In the London music scene, the interesting stuff is mostly underground now because the music business has changed so much in the past few years to become all about boy/girl bands. But there is tremendous innovation here. The enormous diversity of people speeds up the evolution time. It's a good place to be stimulated. And you don't necessarily have to be in clubs to find it. It's on the pirate radio stations, coming out of people's houses and cars. I suppose there is a particular attitude in the air that is conducive to creativity.

The opportunities to work with on the Lunar Drive project would not have been available without the Bahá’í network, and a sense of trust. My life experiences have been tied with the Bahá’í community and patterns of thought such as appreciation and fascination for other people and cultures, new sounds and experiences. Our international community is quite incredible and has a feeling of vast possibility and solidarity.

The working process for future albums will be different again. Although we don't know what will happen with Lunar Drive because everyone is busy with their own projects and travels, it seems like we may get moving on another album. New technology, like my laptop, combined with other equipment will allow for a more mobile system. So instead of getting sound bites and working to them, it will be easier to travel somewhere and collaborate to a much greater degree on site.

Excerpts from Arts Dialogue, October 2001, pages 4 - 10.

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

email: bafa@bahai-library.com

|

|