BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

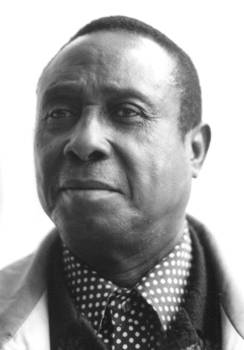

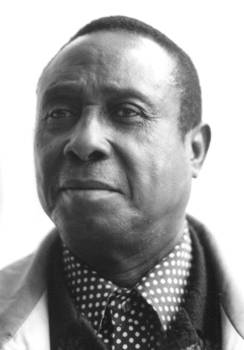

Venancio Mbande

timbula musician, composer,

Mozambique / South Africa

|

Venancio Mbande, 1999

Photograph by Yorum Diamand,

The Netherlands.

|

I don't know how I learnt the timbila

(a large wooden xylophone-like instrument)

-click here for a photo of timbula being played by the group Anumadutchi.

More about the Dutch percussion group, Anumadutchi whom Venancio

performed with in the Netherlands in 1999.

I grew up with it, learning to play from my elder brothers and from playing after school each day with my family in the Zavala district on the southern coast of Mozambique.

There were two levels for playing the timbila. Boys between the ages of 5 and 16 played in the Ngalanga where they learn and were initiated into how to play and dance the timbila compositions. Generally we performed twice a week and often we would have a big fire and then the villagers would come and watch us. The next level was called Mgodo, which means orchestra in my language, Chopi. Only men perform in these and we would perform about once a week with about 30 musicians and 60-80 dancers. Each village in Chopiland had its own Mgodo and there were always competitions to see who was the best group.

Women would also dance but they danced to accompany the male dancers who were the focus of the performances. The dance and music was the focus of a village event in which everyone was involved in one way or another, and being the most important art form it was always held at the chief's place.

|

The timbila was mentioned by a Portuguese missionary in the 1300s and has been performed in the Manjacaze, Zavala, Inharrime and Homoine districts of Chopiland for hundreds of years and on many different types of timbila. Now there are only three types: the Chilanzane, usually consisting of 19 keys making it about a half by two and a half metres long, the Dibhinda (bass) usually 10 keys, and the Chinzumana (double bass) which is usually made up of three large 50 by 40 cm keys. The timbula keys are made out of Mwenjo wood with cut gourds underneath. They are generally played from left to right and always very fast.

The melody sits in the rhythm.

Like many young men from our area, after I

finished school, I went to work in a gold and platinum mine in Transvaal (South Africa). At this mine, like many mines in the area, there was a Mgodo group (of 18 dancers and 15 musicians) and I joined this group, learning as much as I could from them. In 1953 I started my own group of 19 dancers and 19 musicians. At the same time I started making my own compositions and lyrics. I compose these lyrics for my own expression and enjoyment but others see them as political because they are songs about the times we live in. For example one song was about the founder of Frelimo (the first resistance movement against the Portuguese who colonised Mozambique) who was assassinated in 1969.

The musical style I use is in the traditional way of singing with the timbila, as are my compositions, but the texts are revolutionary. That is because they are about life in Mozambique and it is like that.

I compose all the time. My timbila orchestra sings the words while they play. Some recent songs have been about landmines, about how old people are being abandoned by their children, and about bandits stealing our cattle. I don't write against any government. Just about what has happened and the government can see that too, so I have not had any problems as a result of my lyrics. People seem to love them and I think it is because they recognise their lives in the songs.

In 1953 I met the Transvaal musicologist, Hugh Tracey who ended up recording music from many parts of Southern Africa. I bought some wood from him and started to learn how to make my own timbila. Building my own instruments was as important as composing. It meant that now my music was entirely from me.

Music has now almost disappeared in Mozambique because of the civil war that ravaged our country from 1975 until 1996. Life was so hard so there was no joy left to play and so many children grew up without this music. Now it is hard for all artists in Mozambique because there is no social welfare let alone a structure for the arts or any sort of sponsorship. It is a society that is fractured. The timbila players are very old or have died and it is hard work and will take a long time to recreate these arts.

I have a school for the timbila and currently have 14 students, but we have no money so the students can only come in the weekends for lessons. A number of friends found some money to buy a truck for our school so we could collect the wood we need to make the timbila from the bush, 350 km away, but then bandits broke in shooting two of my sons and stole the vehicle. Life here means always having to look over my shoulder.

I retired in 1995 after working in the mine as the kitchen supervisor for 44 years but, just like many other black foreigners living in South Africa, I have no pension. So money is a constant worry as well. I have some land with cattle on it and now we are all hoping that it will rain soon.

The timbila is my area of expertise but I am dependent on others buying the instruments or on sponsorship. I perform every week with my orchestra (of 25 dancers and 13 musicians), but I cannot earn enough from this to survive.

Since 1996 I have performed in Mozambique but I have not performed in other African countries. There is interest and an exchange of music between various African countries. At one stage someone in Zimbabwe had arranged for me to give a lecture there, but the tickets didn't arrive and I have no idea what happened.

In Africa my music is not generally known. I think it is partly because I lived in South Africa for most of my life and partly because I didn't have a good manager.

In 1989 Andrew Tracey (director of the International Library of African Music in Durban), organised a 3-week European tour for my timbila orchestra. We performed in Portugal, Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany and France. Then a Belgian organized another European tour for 2 weeks in 1996. Since then I've toured various parts of Europe with my orchestra about once every two years. I've also travelled to Europe on numerous occasions for single performances such as for a festival in Vienna (Austria) last year.

Daily life is still full of uncertainty and harder for me than it used to be, but in general things are getting better. I have 5 sons and a daughter who play timbila, and a 4 year old son who will join them in the future, and I have students who come every weekend to learn and perform.

More about the Dutch percussion group, Anumadutchi whom Venancio performed with in the Netherlands in 1999.

Interviewed by Sonja van Kerkhoff in November 1999, while in the Netherlands for some performances.

Arts Dialogue, June 2000, pages 6 - 7

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

email: bafa@bahai-library.com

|

|