BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Paul Rayner

painter, curator, New Zealand.

|

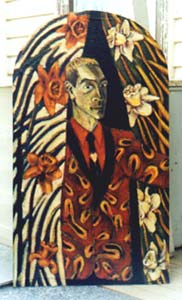

Paul Rayner, 2000.

Photo: Tom Seaman

|

When I was 14, I immigrated from England with my family. In 1979, when I was 20, I moved to Wanganui to work in a radio station and, after a few years, took up working at the Sarjeant Gallery as a general hand. This developed into a job as an education officer, which involved creating programmes and activities in the art gallery.

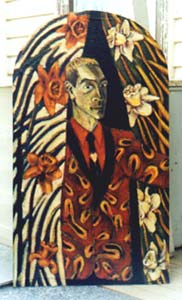

In 1985 I moved to Auckland to study Fine Art at the Elam School of Arts, graduating in painting in 1989. My painting work was informed mostly by popular culture and issues to do with celebrities and self-image. An example is "Self Portrait as Dorian Gray", a work that is in the Sarjeant Gallery collection. Dorian Gray is a character in one of Oscar Wilde's books. The painting connects to the vanitas painting or a memento mori. In the book, Dorian Gray was always young and beautiful. My painting portrays me as a young man surrounded by symbols associated with vanity, decay and death.

|

After graduating, I moved to Wellington to join the team that curated the Parade exhibition in Te Papa, New Zealand's national museum. It was opened in 1998 after a decade of preparation. The term Te Papa is a Maori word for mother earth; it also means 'the ground', and in this case 'common ground'. The museum was designed to integrate all aspects of New Zealand culture. Not only are aspects of Maori and white colonial culture displayed in their own types of spaces and in shared spaces, but also paintings, design, technology and the natural world are exhibited together in various equally valued juxtapositions. The goal was to create a museum space that integrated all aspects of New Zealand culture for all types of visitors. So, currently in the museum there are areas focussing on Maori, Pacific, and colonial cultures, as well as the natural world.

I think that is the reason people find the museum a difficult space, because as a visitor you have to choose your own directions in the spaces. With freedom comes responsibility. The museum is not directing the order in which you encounter, or dictating a particular interpretation or message. It is like a marae (a Maori community space) in spirit because it is open every day and free to all who enter. During each development of the Te Papa project, biculturalism was a crucial aspect. The exhibition we worked on was a long-term exhibition providing an art experience for the general public, with a focus on family groups. The theme we came up with was the new arrival of ideas, technology over time and how this affected what was possible. We thought about that and how we express ourselves creatively in this country.

|

Self Portrait as Dorian Gray, 1988, acrylic on hessian. Collection: Sarjeant Gallery / Te Whare O Rehua Whanganui, New Zealand.

|

The exhibition showed innovations in painting beside innovations in science and the use of our natural resources. For example, we exhibited a Holden Kingswood station wagon clad in corrugated iron by the sculptor Jeff Thomson with a Milan Mrkusich monochrome minimalist painting.

This exhibition was the most controversial one in Te Papa. The criticism came mostly from members of the art community. They were upset that we had displayed a 1959 fridge next to a Colin McCahon painting painted in the same year. McCahon had recently returned to New Zealand after travelling through the United States and being inspired by the contemporary art world there.The fridge was the first in this streamlined style and was a copy of the type made in the States at the time. Both the painting and the fridge were innovations informed by U.S. minimalist ethics. The critics considered it an insult to place a fridge next to a McCahon. Te Papa, however, gives equal value to both innovations. We wanted the exhibit to extend beyond the boundaries of a modernist way of exhibiting, and this required a lot of research into finding connections between the works. Finding a 1959 fridge took a nationwide search. We rechromed and repowder-coated it so that it looked as if it had just come off the assembly line. Ironically, in those days a fridge was a luxury item and was worth 10 times the price of the painting next to it.

Colin McCahon was the first painter in New Zealand to break out of painting in a style that was derived from the mainstays of Western European painting (Cezanne, Cubism, Fauvism, etc), and his innovations in combining text with a sense of the mystical were definitely influenced by his six-month visit to the States in 1959. He worked continuously and prolifically and didn't start to become nationally influential or valued until about the late 1970s. Now many consider his paintings to be icons of New Zealand culture. In a sense it is, but his work was on the cutting edge of postmodernism. Te Papa is creating a postmodernist environment where many strands of cultural practice are given equal spaces...

It is interesting that what was an item of status then is now considered an insult by those that consider a McCahon a symbol of status. It not only reflects a narrow response to our recent cultural history, but also a hierarchical way of looking at what is of value culturally. What is so sad is that it seems as if 90 percent of those with something to say about this exhibition are practising artists who are against the fridge next to a McCahon. It is the art world who has a problem, not the general public, who don't understand McCahon's paintings. Helen Clark, our current Prime Minister and Minister of the Arts, said the thing that was wrong about Te Papa was that it treats a fridge the same as a McCahon. The whole controversy centres on modernism and ironically the fridge is a product of modernist ideology just as the McCahon painting is.

The main argument against Te Papa by the art community is that this type of presentation makes our national art collection hard to see. In response to this, Te Papa has reviewed its policy on its presentation of art and will shortly increase the amount of floor space it gives to works of art. It is a compromise that could signal a return to exhibiting art separately from other aspects of cultural practice.

|

In 1998 I moved back to the Sarjeant Gallery in Wanganui as a curator. The gallery was busy, with just three days before its first show was to go up. It was a memorable show and experience for me. It had to fill a gap in the calendar and was called the "A to Z of art", where artworks from the museum collection were exhibited in alphabetical order.

|

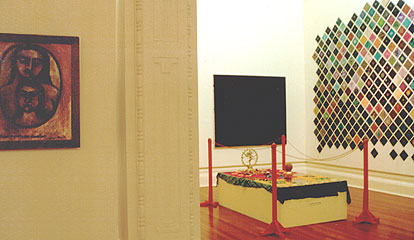

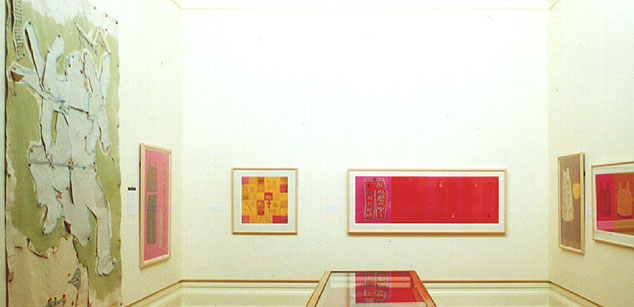

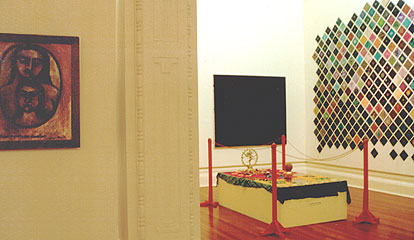

Sarjeant Gallery / Te Whare O Rehua Whanganui, New Zealand. |

Unusual associations were discovered, such as a Frances Hodgkins next to a Ralph Hotere; that is, a 1920's watercolour next to a 1980's minimalist black painting. It was very accessible because it was obvious what the theme was and works that had not been aired for decades got a showing. The Wanganui public particularly appreciated this because their appreciation of art is on the populist side of things. A marble life-size sculpture of nude male wrestlers, based on a Greek third-century original, was one of the most popular in our 4000 piece collection and had been exhibited in the central space of the gallery for 58 years. When it was removed from there a number of years ago, there was an uproar.

As a curator here I have been encouraged to develop the various spaces in the gallery along the lines of historical evolution. For example, one front wing houses a permanent yet changing collection of the Wanganui post-Impressionist artist, Edith Collier (1885 - 1964). She was a contemporary of Frances Hodgkins and there are around 600 pieces of her work in our collection. The other front wing always has shows that draw on work up around the mid-twentieth century. This is so that the average Wanganui visitor doesn't feel uncomfortable with the unfamiliar. The back wings have more contemporary shows of work by invited artists and touring shows. We have about 20 to 25 shows and about 30 percent of these are touring shows. I curate the rest.

There is a strong emphasis on curating shows that incorporate works from the gallery's collection. This gallery has been around since 1919, and is one of the longest continuously operational museum spaces in the country. Because of this, it has amassed an enormous and, in many ways, unique collection of works. Until about 1920, nearly all the work was British and European, which has provided real highlights for a colony like us and a city this small (population 40, 000).

In August 1998, I curated "Spirit of Folk Art". It was the first time I realised how powerful art about belief was. A few works from that show looked beyond the natural world, which impressed me in contrast to the ones focussed more on the everyday world. Then the "Ka Ora - to live" show extended my interest in the metaphysical. This theme took people on a journey through various rites of passage in the 10-week show incorporating about 70 sculptures, paintings, photographs and prints. I started with the medieval concept of the seven ages of humanity, beginning with conception/birth. I aimed for a good mix of art influenced by Maori and European perceptions of life. The diverse views gave the show its

depth and once again the spiritual came to the fore. This time the combination of the material and the spiritual aspects of life was more consciously developed.

|

"Who Am I? Belief and Identity in Art", 2000

Left to Right: "There is only one direction (Mary and Jesus)", by Colin McCahon, Hindu altarpiece and paintings by Wanganui artist, Prakash Patel. Read the review of this show by Sonja van Kerkhoff.

|

With the "Who Am I" exhibition in 2000, I was first interested in who in our community was working or had addressed identity and belief in their work. I approached about 10 artists in the Wanganui region and offered them space. Then I juxtaposed their work with other thematically similar pieces drawn from the collection or from other sources.

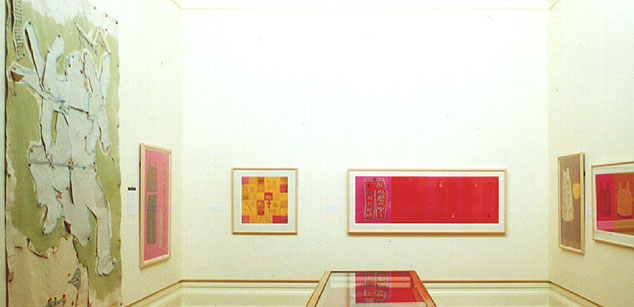

Faith McManus is a printmaker and I selected her "a haka mana" works which are based on Maori vowel sounds. They have a child-like innocence, yet there is a lot more going on in the bright doll-like cut-out clothing forms, such as language as a garment people wear as a form of identity.

|

"Who Am I? Belief and Identity in Art", 2000

Left to Right: "Button Down" by Phillip Trusttrum and the silkscreen series by Faith McManus.

|

She has Maori affiliation, and this work relates to her learning the Maori language, making the work personal and honest. Joanna Paul's watercolour series of 10 works entitled, "Frugal Pleasures", uses language to clothe as well. Her whole series was inspired by the story in which Horace praises the rural over the urban. Her compositions of jugs, plates, fruits, and Latin text are juxtapositionings of culture. The natural and the cultured appear on tablecloths in pastel hues. The freshness of the colours and loosely drawn forms celebrate the simple pleasures of life.

I developed a number of themes within the show, and one of these was on the use of the cross as a symbol of Christianity. Rebecca Pilcher's work, "Cleanliness is next to Godliness" is an arrangement of about 36 soapbars in the form of a crucifix, placed on a wall above a bathroom sink. She is a recent graduate from the Fine Arts Degree course at the art school here. Another is a tiny circular painting, framed in thorns, of Christ's face set against a glowing background. This sits beside a large expressionist work by Wanganui artist Michael Hajie, in which he depicts Christ prone and surrounded by mourning figures. The focus of the painting is an intimate insight into the mourners' grief. I developed a number of themes within the show, and one of these was on the use of the cross as a symbol of Christianity. Rebecca Pilcher's work, "Cleanliness is next to Godliness" is an arrangement of about 36 soapbars in the form of a crucifix, placed on a wall above a bathroom sink. She is a recent graduate from the Fine Arts Degree course at the art school here. Another is a tiny circular painting, framed in thorns, of Christ's face set against a glowing background. This sits beside a large expressionist work by Wanganui artist Michael Hajie, in which he depicts Christ prone and surrounded by mourning figures. The focus of the painting is an intimate insight into the mourners' grief.

Prakash Patel is another Wanganui artist I invited to participate in the show. He made an installation with his brother and sister-in-law. It has a Hindu shrine in the centre, which is surrounded by abstract paintings by Prakash. The shrine gives the abstractions an extra context to his Eastern philosophy and Western art practice. I incorporated children's art that looks at identity, as well as work from an adult workshop on milagro (miracles). This workshop was given by Ana Flores, a Cuban-American artist who was a guest teacher at the art school. I also took some works by children, made in workshops run by the current artist-in-residence, Jeff Thomson, on the "Who Am I" theme.

|

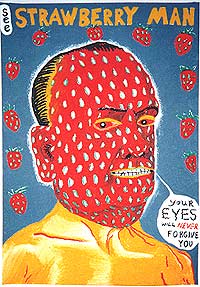

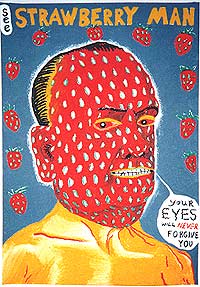

Strawberry Man Strawberry Man, 2000, oil pastel on paper by Paul Rayner.

|

A trademark of the show was how I'd mixed and matched various genre including traditional museum artefacts such as a Fijian Mbure (a woven God-Temple), a 19th century Maori Bible, and Christian relics. A number of works were added to the show after the opening, such as the works from the milagro workshop, which introduced another layer: the idea of the miracle and healing in our daily lives. The participants had each made a clay object that offered thanks to a deity.

Part of my work as curator is managing the artist-in-residence programme, which has been running since 1986. Artists are given the historic Tylee cottage to live in and a small stipend. Usually the artists stay 6 to 12 months and take the opportunity to develop new ideas or techniques, often with an opportunity to show in the gallery at the end of their residency.

I also continue my own practice. Principally, I am a painter. In the last three years, I have been working on ironic portraiture, which plays on popular culture, such as comics, stardom, and the idea of beauty and fame.

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

email: bafa@bahai-library.com

|

|