| Visual Arts | U.S.A. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Mark Tobey painter, U.S.A. |

|

This text by Sonja van Kerkhoff is extracted from the books mentioned. |

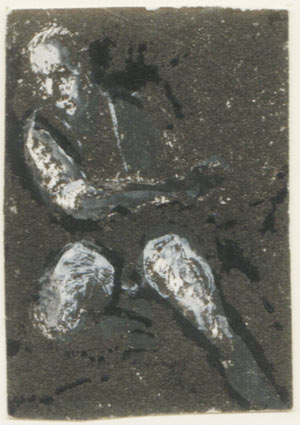

Movement Round a Martyr, (slightly cropped) oil on canvas,

by Mark Tobey. Bequeathed to the U.K. National Bahá´í Community by Constance Langdon-Davies. Photo: Sonja van Kerkhoff. |

|

|

to know of what a real unity is composed

- not uniformity, but the unity of related parts. I have no hesistancy in including philosophical colourings, any more than I would hesitate to say that back of any person, and I mean each person, there must be his or her metaphysics.

First of all, I want the desire to create; for therein lives the will to continue to live in a new way - to add to your house more vistas of being. For I believe that back of all great achievement is a richness of being...' That Mark was a marvellous teacher of art was apparent at Dartington Hall. Twenty to thirty chose to come to his free drawing class one evening each week. - artists, dancers, musicians, housewives, servants and gardeners... he taught everything, even by silence... "

|

Detail of Movement Round a Martyr by Mark Tobey.

Detail of Movement Round a Martyr by Mark Tobey.

|

Mark Tobey was born in Wisconsin, U.S.A., and grew up in the countryside with a great love for nature. As a child he participated in Saturday art classes at the Institute of Art in Chicago for two years - the only formal art training he had. Then his father became ill, forcing Mark to work. Beginning in 1909 as a blueprint boy in a steel mill in Chicago, by 1911 he was working as fashion illustrator in New York, and later as a portrait painter in New York. |

There he met the painter Juliet Thompson, who introduced him to the Bahá´í Faith which he joined in 1918. In the 1920's while becoming known for his caricatures of theatrical people, he was concerned with reacting against "the Renaissance sense of space and order" "to smash form to melt it in a more moving and dynamic way"

|

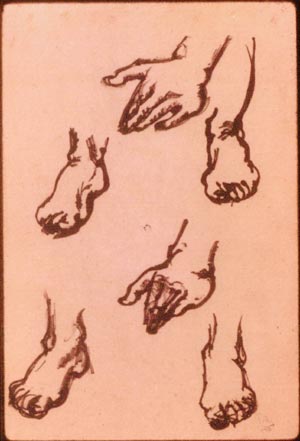

Untitled figure of a man, ink and pastel on paper. Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl. |

|

but by our very lives [ -- to] the fourfold plan of our very being which manifests in the outer, through form and action and within us, as attitude and thought."

(Mark Tobey, in the essay 'One Spirit', cited in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief, by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 44. Punctuation has been altered.) |

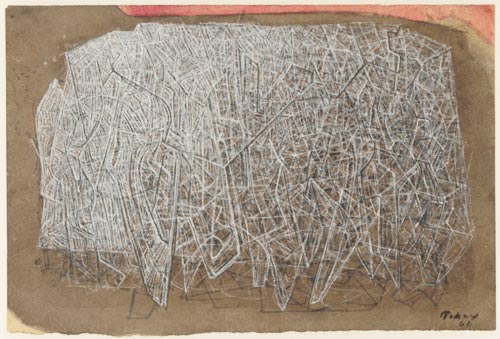

Detail of The Red Tree of the Martyr, 1940, tempera, 9 and a half by 13 and a half inches, by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon.

Detail of The Red Tree of the Martyr, 1940, tempera, 9 and a half by 13 and a half inches, by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon.

|

Although he is now renown for his 'white writing' paintings of the 1950's and 1960's, which established his international reputation and are found in museum collections, he was not intending to create a new style. He was not concerned with creating a style or being original. Each painting was the result of a process that had the freedom to go in a number of directions. |

| So he didn't limit his approach to a particular 'signature' even after his larger abstract paintings had made his reputation. He also continued to paint figuratively, to paint small, and to experiment with media such as in printmaking. |  Lovers of Light, 1960, tempera, 4 and a half x 6 and a half inches. Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl. |

Aerial Centers, 1967, tempera on board. Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl. |

"Over the past 15 years, my approach to painting has varied, sometimes being dependent on brush-work, sometimes on lines, dynamic white strokes in geometric space. I have never tried to pursue a particular style in my work. For me, the road has been a zig-zag into and out of old civilizations, seeking new horizons through meditation and contemplation. My sources of inspiration have gone from those of my native Middle West to those of microscopic worlds. I have discovered many a universe on paving stones and tree barks. I know very little about what is generally called "abstract" painting. Pure abstraction would mean a type of painting completely unrelated to life, which is unacceptable to me. I have sought to make my painting "whole" but to attain this I have used a whirling mass. I take up no definite position. Maybe this explains someone's remark while looking at one of my paintings: "Where is the center?" " (Extract from a letter dated 1/2/1955 from page 13 in the Whitechapel catalogue, cited in Arthur L. Dahl's essay, The Fragrance of Spirituality, in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 36.) He was interested in independent investigation through the medium of paint. Each work is the result of his investigation of form and space. At the same time, the expression of spirit was intrinsic to his artistic approach. "To me an artist is one who... portrays the spirit of man in whatever condition that spirit may be." (Letter to Arthur and Joyce Dahl, 26 April 1957, cited in Arthur L. Dahl's essay, 'The Fragrance of Spirituality' in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others., p. 33.) |

"At a time when experimentation expresses itself in all forms of life, search becomes the only valid expression of the spirit..." (Exhibition catalogue, Willard Gallery, New York, 1949, cited in Arthur L. Dahl's essay, The Fragrance of Spirituality, in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 33.)

After a short unhappy marriage, he left New York in 1922 for the more spacious and relaxed atmosphere of Seattle. A friend was returning home to Seattle and offered to share train space and a bag of oranges. There he found work teaching at the Cornish School, where his methods concentrated on encouragement, love for art and developing the student's fantasy, rather than following structured procedures and principles. In those years, his interpretations of Cubism helped him to see form as the result of movement (inspired by watching the movements of a fly) rather than calculation. In 1923 he met the Chinese artist, Teng Kuei, who taught him the technique and philosophy of Chinese calligraphy.

"I have just had my first lesson in Chinese brush… The tree is no more a solid in the earth, breaking into lesser solids bathed in chiaroscuro. There is pressure and release. Each movement, like tracks in the snow, is recorded and loved for itself. The Great Dragon is breathing sky, thunder and shadow; wisdom and spirit vitalized." (Mark Tobey, Reminiscence and Reverie, Magazine of Art, October 1951, cited in 'Mark Tobey 1890 - 1976' by Arthur L. Dahl, in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 5.) |

|

Mark Tobey was also influenced by Northwest and Alaskan Indian art. In 1925 he was in Paris for several months before visiting the Bahá´í Shrines and the World Centre at Haifa where he spent an hour with Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian.

"…I made the Guardian laugh, which seemed to please him. Of course in Haifa many things happen and yet all seems to melt in time which is no time." (Interview in 1963, cited by Arthur L. Dahl in 'Mark Tobey 1890 - 1976' in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 5.) For the following three years Tobey divided his time between Seattle, Chicago and New York, teaching, painting and exhibiting. Alfred H. Barr saw some of his paintings in a New York cafe gallery and selected several for an exhibition of American painters at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1930, when his teaching post was threatened by the poverty caused by the Wall Street Crash, he accepted an offer from Mr and Mrs Elmhurst to be head of painting at the progressive school at Dartington Hall in England. In his 8 years |  Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl.

Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl.

|

there he associated with many artists, such as Aldous Huxley, Rabindranath Tagore, and the dancer Shankar. He formed a close friendship with the South African painter, Reginald Turvey and the English potter, Bernard Leach. On parting in the mid thirties, the three made a pact to meet up again at the 1963 International Bahá´í conference, which they kept.

With war imminent, he moved back to Seattle in 1938, where he taught and painted and gradually become better known. "Most of the characteristic 'white writing' works were painted in the 1940s, when he was in his fifties, or later. The works with Bahá´í themes and titles were mostly done in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Sumi paintings, very different from his other works, but in Tobey's judgement among his most significant contributions, were created in 1957, when he was 66. The experimentation with monotypes, which went on for more than a decade, began just before the Louvre exhibition in 1961." (Arthur L. Dahl, 'Mark Tobey 1890 - 1976', in Mark Tobey / Art and Belief by Arthur L. Dahl and others, p. 6.) |

Untitled monotype, 1969, by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon.

Untitled monotype, 1969, by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon.

|

In 1948 he represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale and was awarded the Venice Biennale International painting prize in 1958. The last American painter to receive this had been Whistler, in 1895. In 1960 he bought a 500 year old house in Basel, Switzerland and moved there with his close friend, Pehr Hallsten and his secretary Mark Ritter. |

In 1961 the Paris Museum of Decorative Art, in the modern wing of the Louvre, exhibited 285 pieces of his work. Tobey was the first living non-French artist to receive such an honour. Numerous exhibitions followed in major European and American cities, climaxing in the 1974 "Tribute to Mark Tobey" exhibition in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC. Over half of the 70 works had been painted from the age of 67. So although plagued by illness in his later years, he continued to work productively until about three years before his death.

|

"Tobey had a strong and memorable personality, and made a legion of devoted friends… His humanity was particularly apparent in his close personal relationships, such as with his Swedish friend Pehr Hallsten. They were devoted to each other for more than twenty years, |  Animal Sketches, Ink Collage, 1949 by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl.

Animal Sketches, Ink Collage, 1949 by Mark Tobey. Collection of Arthur Lyon Dahl.

|

but it was not always easy for Mark. Since Pehr suffered from diabetes and often needed special attention and was often difficult to deal with… But Mark needed this outlet for his urge to nurture, and took wonderful care of Pehr." "Tobey's creativity extended to the other arts. He wrote a considerable amount of poetry..." (ibid p. 12)

It is the works themselves will stand the test of time, rather than the theories of abstract expressionism. So perhaps the work of some artists of those years, such as Tobey, Pollack and Rothko, could be re-interpreted as a modernist rediscovery of the spiritual, as mysticism in paint? |

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands email: bafa@bahai-library.com |