|

|

Abstract: Some history of Sayessan, a Bahá'í village near Tabriz; of Mullá Asad’u’lláh, who prophesied the coming of the Bab; of Bahá'u'lláh's gift of seed potatoes; and Sayessani pilgrims travelling to Akka to meet Abdu'l-Bahá. Includes pictures. See also a scan of the article at Bahai.works. |

In Írán there are villages where many of the people embraced the Bahá’í Faith in the early hours of the dawn of the Age of Bahá’u’lláh. It is amazing how these illiterate and incredibly impoverished people, ignorant of the outside world, could ever comprehend the significance of this great Cause with its world-embracing power, and its many new principles fitted for an age they could scarcely imagine. However, when one visits these villages to meet these radiant souls, the secret of their early attachment to the Faith is uncovered. In these remote places were a few divinely inspired men, luminous stars who, in the last hours of the night prior to this glorious dawn, prepared their fellows by telling them about the impending advent of the Promised One, and by warning them against heedlessness. Each one of these villages has had its own hero and its own unique history.

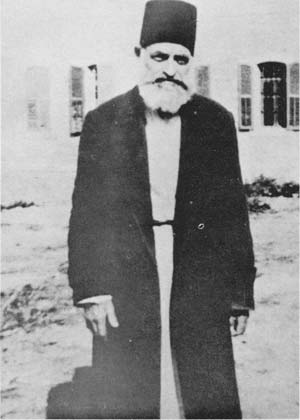

Isma'il Agha of Sayessan the trusty gardener of the Master who also served the Guardian for many years. |

Mullá Asad’u’lláh was the sage who trained and readied his fellow Sayessanis by constantly reminding them of the Great Day, the Day of Judgment, that Day when sons would run away from their fathers, and when mothers would choose to abandon their own children. In his exhortations he emphasized that each one must purge his heart of all else save the love of the Promised One, so that his penetrating effulgence would accept their mirror hearts as its abode.

One day when Mullá Asad’u’lláh, followed by a group of his students from Sayessan, was walking through a narrow lane in Tabriz, a well-known mujtahid of that city passed by. He was Mullá Muhammad-i-Mamaqáni, one-eyed, energetic, a vehement controversialist and traditionalist, a man accorded great respect by the people, who always gave way before his passage. But Mullá Asad’u’lláh covered his face with his cloak, refusing to look upon the countenance of this man of high priestly estate. The companions were astounded, for their mentor was a model of humility and temperate good-conduct.

Returning to the village, the young disciples enroute asked Mullá Asad’u’lláh to explain this apparently grave breach of etiquette, this seeming almost-insult to a highly placed leader of religion of great prestige in the city and region. To their even greater astonishment he replied, with deep feelings of sorrow and anger, that "This man will sign the death warrant of the Promised One, and I did not desire to see his face. Beware! When you hear the news of His advent, and of His martyrdom in Tabriz, you must all respond to His call!"

Villagers Accept The Báb

This saintly soul, his seer's vision having readied his followers, died before the Advent. But those he had trained and sensitized, his faithful disciples, remained vigilant, listening for reports of a Great One who would be done to death by the order of the same one-eyed mujtahid and some of his colleagues. Thus expectant, they heard in 1850 of the execution in Tabriz barracks square of a certain Siyyid ‘Alí Muhammad of Shíráz, one who called Himself the Báb and who asserted that He was the Qá’im. The Sayessanis gathered all news of this young man who threatened the authority of the priests and the governor so gravely that these men of power felt He must be killed. And it was true. The Promised One of their prophecies and of Asad’u’lláh's vision had come. In a wave of excitement and conviction 2700 of the almost 3000 inhabitants of the Sayessan area became Bábís, embracing the new Faith of God. Isolated from the central pressures of government, they continued bold and fearlessly outspoken in their new Faith, and so became the target of frequent persecutions. Many times daring souls among them were taken prisoners to Tabriz, and even to Tihrán. But they never wavered in their constancy and fortitude. And when there came the news to Írán of the Declaration of Husayn-'AH of Nur, that greatest Bábi known as Jináb'i Bahá, or Bahá’u’lláh, in Baghdad, all rapidly accepted the new Teacher who was the fulfillment of the Báb's own Book.

Bahá’í youth of Sayessan advancing in two rows to receive their guests. |

Travel to 'Akká

During the days when Bahá’u’lláh was under house arrest, imprisoned in the city of 'Akká, the first small group of Bahá’ís from Sayessan set out on foot, circa 1878. After crossing more than.700 miles of desert and mountains and enduring many hardships they at last attained to the presence of their Beloved One. Radiating such love and simple sincerity, and uttering such innocently provincial remarks, by their zeal and enthusiasm they brought great happiness to the heart of the Blessed Perfection, saddened by the burdens of His incarceration.

They wore their Sayessani clothing, suited of course to the far more rigorous climate of the northwest mountains of Írán. Their large fur hats became the particular target of the street children in 'Akká; these wild and untrained children found them so strange and amusing that they followed the pilgrims about, jeering, taunting, making fun of them ceaselessly. When they told ‘Abdu’l-Bahá of this ridicule He simply advised them to wear the ordinary fezzes of the men of 'Akká. On the very next day they came into the Master's presence each wearing a newly-acquired red fez. He smiled infectiously, and with appreciation called them "the red-hatted soldiers of the Blessed Beauty."

Soon the believers from Sayessan became familiar with the prevailing bitter conditions of confinement within the fortress of 'Akká. Their hearts brimmed with sorrow for the Holy Ones, for they were surprised that such inadequate food was given the exiles, with no fresh vegetables. The bad-tasting water, the poor diet, the prevalence of epidemics of every kind, the barren city with scarcely a blade of grass inside its forbidding double walls, all evoked sadness and a deep rage. Worst of all, the Blessed Beauty with His great love of the open spaces, of the mountains and the gardens, of flowers and trees and all the beauty of the natural world had not been able to walk abroad for about nine long years. Therefore, one day when in His presence the pilgrims opened their hearts and entreated Him:

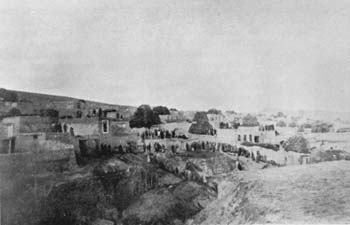

The Bahá'ís of Sayessan gather at the entrance of their village to receive their guests. |

"We cannot," replied the Beloved.

"We promise that the weather will be more agreeable, and we will do everything we can to make you more comfortable."

"We cannot. We are imprisoned here."

"Imprisoned?" they replied, with tears in their eyes. "Imprisoned! Who could ever do that to you? You are the King of this world."

But the Blessed Beauty could not be released from bondage even by these boldest and most resolute of His followers, for God's destiny had ordained His lifetime stay in the Holy Land, that place of fulfillment of prophecies for all mankind.

Bahá’u’lláh's Gift to Sayessan

One day they knew that they must return, full of sorrow that they could not rescue Him as they desired. But before their departure Bahá’u’lláh gave them some of the simple food of the prison, calling their particular attention to the potatoes in the meal. "Plant this in your village," He ordered. "It is good." Since they were farmers by occupation, they learned eagerly from the local growers of potatoes about this strange vegetable. And on their departure they carried back a stock of seed potatoes for planting in their fields. There in Ádhirbáyján soil the potatoes flourished, as the Sayessani Bahá’ís adopted the "new" crop advised by Bahá’u’lláh. As time passed, the potatoes were adopted by the farmers of the area, and became so staple and vital a food, so much a supplement for the grains upon which they had perennially depended from time immemorial, that several times the whole province was relieved by potatoes of Sayessan of the threat of famine which so often afflicted it.

The sorrows that all had felt in 'Akká, that grim city, continued throughout the long journey homeward across desert and mountains. It continued during their days of recounting to their fellows what they had heard and learned and confirmed during those priceless hours of spiritual bounty. So touched were they by the deprivations of the Blessed Beauty that they resolved to do what they could about it.

Among the villagers who had travelled on that pilgrimage were two who bore the same name, Muhammad. As there were no family surnames to distinguish them one from the other, the friends called them Muhammad the first and Muhammad the second. Together they suggested to their fellow Bahá’ís that nothing could be more befitting than flowers for such a Beloved. And what flower better than the fragrant narcissus, in Persia a symbol of purity and love, a symbol too of the coming of the spring and the joyful passing of life out from the darkness and cold of winter!

One of the oldest photos of the friends of Sayessan. Third from the left is one of the two who carried the flowers to 'Akká. |

‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the arrival of the bearers of the narcissi to the first group of pilgrims who visited Him at the end of World War I, in 1919. "When the end of their wearisome journey drew nigh, and the city of Akká was unfolded to their expectant eyes, and when their gaze fell upon the majestic mansion which marked the limit of their destination, they forgot in a glance all their sufferings and cares, attained the gate with sore feet, swollen and blistered, and falling prostrate on the ground laid at the feet of the Blessed Beauty the token of their undying devotion, which they carried with such zeal and love. O, what a shower of blessings and of bounty and of favor were poured upon them! Their gift of living beauty was not only accepted, but was considered to be the most precious gem that could ever be presented, the richest and finest gift in the world. To His bestowals and expressions of acceptance and appreciation these pilgrims muttered repeatedly and wholeheartedly their sincere wish of 'Janem sanah ghorbanela! "Make me the sacrifice; redeem and save my soul!"

Notes: So proud were the families of these two valiant Bahá’ís that they adopted the names "The First" and "The Second" as their surnames when this was legally required in recent times. Hence these Sayessani families are now identifiable throughout the Bahá’í world by their last names: Awwal and Thani.

In the winter of 1935, in company with dearly loved Davood Toeg, then Chairman of the National Spiritual Assembly of 'Iráq, and with Rahmat Ala'i of Tihrán, the author visited Sayessan, thus following in the footsteps of Martha Root and Keith Ransom-Kehler. Hundreds of young boys and girls, knowing of our coming, walked miles to meet us and, with their colorful dress and high spirits, formed two most attractive and picturesque guide groups taking us to their famous village.

Some Bahá’í women in Sayessan in their colorful dress. |

Startled by the question, Rahmat answered: "Yes, I am; but how did you know me whom you have never seen before?"

A very beautiful smile appeared on the old man's face, and he said: "When some of us were prisoners because of our Faith, your father as the court physician used to come to the prison to see the sick prisoners. We Bahá’ís were in a single room. He used to come and embrace every one of us. I can't see you, but when you embraced me, I smelled his perfume.

There are those who recognize every perfume: the perfume of good men, the fragrance of the narcissus, but particularly the perfume of the spirit of God in the world.

So remarkable these Bahá’í are in their love to the friends and hospitality towards them that in their intense longing to remember the blissful occasion of their visits they name children after their guests. There is no wonder if you see a little charming girl passing by and the people call, her "Miss Martharoot" or "Mrs. Kehler Khánum."

|

|