|

|

Abstract: Includes passing references to Abdu'l-Bahá and Akka, a description of life in Haifa at the time, and some history of Laurence Oliphant. Notes: This book is online in a variety of formats at archive.org. |

The Call of Mt. Carmel

by Maude M. Holbach

published in Bible Ways in Bible Lands: An Impression of Palestine, pages 5, 6, 8, 9, 16London: Kegan Paul, 1912

1. Text

[page 1]

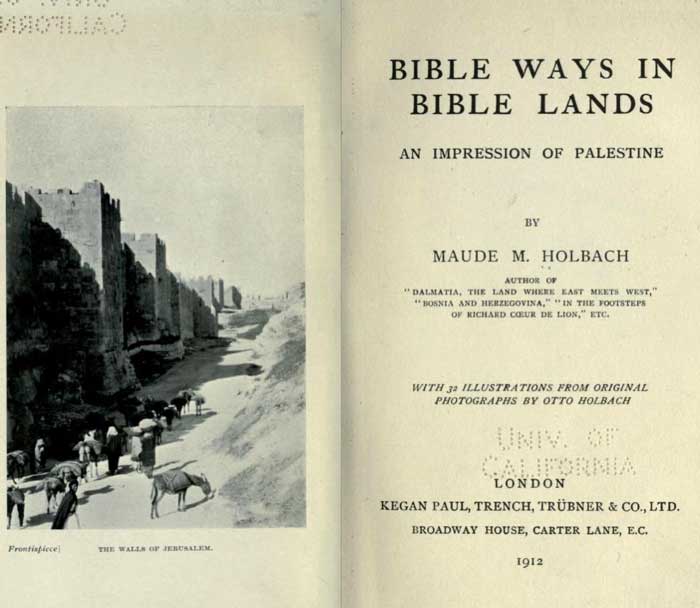

I FIRST saw "Holy Land" from the deck of the Dunottar Castle at anchor in the Bay of Haifa. It was a cloudless spring morning, and in the clear air of Syria the houses on the shore, though really a mile distant, seemed close by. I have an impression of white houses with flat roofs backed by green hills — a description which would fit many a town in the East — yet Haifa does not look wholly Eastern; it lacks the many minarets of Oriental towns where Islam is paramount. I felt before I landed that this was indeed "the Holy Land!" I knew that though we

[page 2]

have no record that our Master [i.e., Jesus. -J.W.] ever walked upon the seashore that lay between me and the little town, or trod the streets of "Khof," or "Khafah" (referred to in the Book of Judges as the "haven by the sea"), He certainly wandered over the hills, then dotted with prosperous towns and villages that lie between here and the Lake of Galilee; for His lowly home at Nazareth was only fifteen miles away.

If I were going to live anywhere in Palestine I should certainly choose Haifa, as the cleanest town and the one most beautifully situated in the whole country! It lies between the mountains and the sea at the foot of Mount Carmel, which is not, as I always imagined before visiting it, a single mountain but an extensive range, triangular in form.1

Some happy day when I revisit Palestine I hope to pitch my camp upon the sacred mountain, to explore its hills and valleys,

- The eastern side from the apex of the triangle is thirteen miles in length, the western twelve, and the base, which runs parallel with the sea, nine.

[page 3]

wooded glens and wild gorges, and penetrate into the hidden caves which were such secure hiding-places in Bible days, that they are mentioned in the Book of Amos as an illustration of the secrecy that God alone could lay bare.

In those far-off times the mountain was covered with a dense forest, now it is covered in spring with flowers, and when I visited it the slopes nearest to Haifa, which are crowned by the world famous Carmelite monastery, were aflame with the scarlet anemone which is the "lily of the field" of our authorised version, and to which Solomon's royal robes were likened.

There is a charming legend about the flower which may have been known to our Lord, according to which Hiram King of Tyre sent, with the cedar wood for the building of the temple, a present to King Solomon of a splendid scarlet robe, dyed with the famous Tyrian dyes (which, by the way, were made from a little shell-fish that may still be picked up by hundreds on the

[page 4]

beach). The gorgeous colour delighted Solomon's heart, till one day a child brought him a bunch of the blossoms of the scarlet anemone, and he saw that his treasured garment looked but dull beside the shining blossoms, and pointed out to his courtiers how the work of men's hands paled before God's handiwork.

Alas! I did but touch the fringe of Carmel! It is still almost an unexplored country, and wild life abounds — leopards, hyenas, wild boar, and gazelle roam over its hills and valleys — tourists who sleep at Haifa are generally content to walk or drive to the monastery and hasten on to the famous sites of New Testament history at Nazareth and Galilee — so the animals have the mountain solitude to themselves.

Is it only coincidence that another school of the "Sons of the Prophets" has established itself upon Mount Carmel — that young men are coming there from all over the Eastern world to sit at the feet of the teacher who believes it his divine mission to reform not

[page 5]

Islam alone, but the religions of the world? I believe that portion of the western world that has heard of the Persian teacher "Abbas Effendi" (and it is an ever-increasing portion, for his recent brief visit to England drew the attention of our Press), with a few exceptions of advanced thinkers who have taken the trouble to study his doctrines, looks upon him as the founder of a "new religion." As such he was described to us by an Englishman living in Palestine and knowing him personally, but investigation since has shown me the description was misleading.

If the author of "Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi,"1 who spent a month at Acre to investigate the teaching of Bahaism at the fountain head in December 1902, did not view this remarkable religious movement in too favourable a light it must inevitably increase the spirituality of all who come within its influence, whether Christian or Moslem, for he tells us in his introductory chapter: "It recognises every other religion

- Myron H. Phelps of the New York Bar.

[page 6]

as equally divine in origin with itself. It professes only to renew the message formerly given by the Divine Messengers who founded those religions ... no man is asked to desert his own faith: but only to look back to its fountain-head and discern, through the mists and accumulations of time, the true spirit of its founders." Is not this the crying need of the world to-day, that we all act up to the faith we profess? What a wide step towards universal brotherhood to "recognise every other religion as equally divine!"

Abbas Effendi once said in answer to an enquirer, "The Spirit is the same everywhere! Under whatsoever name men address Him, He will respond to their call." In other words, his mission is "not to destroy but to fulfil," not to tell men that they have prayed amiss, but to urge them to live "more nearly as they pray." Abbas Effendi is in line with the great spiritual movement which has arisen in the West, and found expression in Christian Science

[page 7]

and New Thought in the importance he attaches to the power of thought. "Every deed of life," he says, "is a thought expressing itself in action; it is the actual mirror of the man within."

He is in line with our most advanced thinkers, philosophers, and students of human nature in the importance he attaches to character building. "Therefore," he says, "we must be active — we must be up and doing. Our deeds build up our characters, and the building of our characters is our task. Life in this world is for this purpose. . . . If heredity has not given us the qualities of character necessary for our high moral and spiritual advancement, we must labour to build up a new structure within ourselves which will be adequate to that aim. Each man must look to himself and within himself to find his errors and weaknesses."

This is not the dreamy mysticism we are apt to associate with an Eastern sage — it is a philosophy of life calculated to

[page 8]

"strengthen the feeble knees," and make us ashamed of pleading our environment or ancestry as an excuse for our laziness — it will not permit us to "put our ain burdens on the Lord's back!"

And the teacher lives the life he preaches, taking but four hours' rest in the twenty-four, and but one meal a day after his cup of tea that follows his prayers at sunrise. He labours incessantly — teaching, distributing alms to the poor, and carrying on a vast correspondence. An interesting comparison may be drawn between Abbas Effendi's life of rigid self-denial and work, and that of the leader of a great religious movement in the Western world. General Booth, who likewise is, as all the world knows, able to reduce his bodily needs to a minimum, and yet has a capacity for work far exceeding that of the average man of far younger years.

Self-denying, however, as is Abbas Effendi's life, he does not believe in the rigid asceticism that cuts itself off from

[page 9]

mankind. He has left for a time his home on the slopes of Carmel to come to the Western world. When I was at Acre, he was at Alexandria — that battle-ground of the Church and the Philosophic Schools in the first centuries of Christianity — now he has come to the throbbing heart of our own London, which needs his message hardly less than his native Persia.

I must beg my readers pardon if I have digressed too much from the beaten path to dwell on the Sage of Haifa who in God's Providence was so wonderfully brought as a prisoner to Acre, and led to make his home and teach his followers so near to the Galilean Lake, which was the scene of our Lord's earthly ministry.

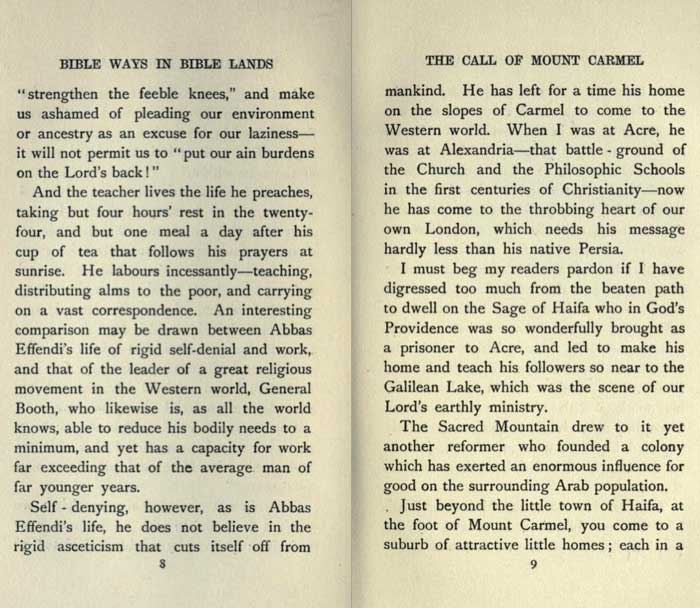

The Sacred Mountain drew to it yet another reformer who founded a colony which has exerted an enormous influence for good on the surrounding Arab population. Just beyond the little town of Haifa, at the foot of Mount Carmel, you come to a suburb of attractive little homes; each in a

[page 10]

well-kept garden, surrounded by highly cultivated cornfields and vineyards that are an object lesson in the fertility of the soil of Palestine when properly cultivated.

This is the German colony founded late in the sixties by Professor Hoffman of Wurtemberg, a University professor and minister of the Lutheran Church. Professor Hoffman was a reformer, and the fate of most reformers was his; indeed, there is a certain likeness in his story and that of the founder of the Bahá'ís, Ali Mohammed. Both aimed to reform the state religion of their country, and both came into collision with the ecclesiastical authorities. The Persian reformer, in a semi-barbarous land, paid for his opinions with his life; the German, belonging to a civilised nation, was merely expelled by the Lutheran Church, just as its founder Luther had been from that of Rome.

That Dr Hoffman, like Mohammed Ali, had a large following, is proved by the petition signed with twelve thousand names

[page 11]

he presented at the Diet of Frankfurt praying for church reform. Perhaps if the crown of martyrdom had been his, they would have increased like the Bahá'ís; as it is they are represented only by three colonies in Palestine, originally composed of those who followed their revered leader into exile, but though small in numbers, the influence of the three hundred German colonists at Haifa on the surrounding Arab population has been very great.

By the simplicity and sincerity of their religion, the scrupulous honesty in their dealings, and the industry and harmony of their lives, this little band of men and women have held high the standard of Christianity, and commended their faith to the world.

Nor is the moral benefit of a business and industrial community setting a living example of practical Christianity all the advantage that Haifa has denied from the German colonists. Their industry has been the corner stone on which the trade of the port has been built up, till it has

[page 12]

become one of the most prosperous towns on the coast. The Arabs have imitated the improved methods of agriculture of the German farmers, and land has increased in value enormously. Before their coming carts were unknown, and all inland transport had to be carried on by means of beasts of burden laden with pack saddles, as it is in Morocco to-day.

The road from Haifa to Nazareth, one of the first in Northern Palestine, was made by the colonists at their own expense, and did much to reconcile the local government to the new comers, whom they at first treated with marked hostility. Life was far from a bed of roses for the Germans in the early days of the colony, for though none of them possessed much means, they were taxed three and four times as much as the natives by the unscrupulous Turkish officials.

The faith that the second advent of the Messiah (which their leader's Bible studies had brought him to the conclusion was approaching) would occur in Palestine, sustained the

[page 13]

colonists in their struggle, and now, firmly established with "their lamps burning," they wait the coming of their Lord.

Strange and sad it is that even in religion there should be rivalry; that all good men working for the spiritual progress of the world cannot join hands as brothers. The monks of the Carmelite monastery (which claims direct succession from the School of Sons of the Prophets) overlook from the lofty site of their beautiful monastery the modest homes and smiling fields of the German farmers, whose lands join their own. Many good and noble men there have been among the fathers, notably that brave friar who, sustained by faith in God, begged throughout Europe to raise the money to rebuild the convent after its destruction by the French, but local report says they held aloof from, if they were not "covertly hostile" to, the Protestant Germans in their early struggles; and there is a painful episode related by a modern writer of something like a battle royal over

[page 14]

the boundaries, when the townspeople, aided by the Germans, tried to pull down the wall by which, they claimed, the monastery had enclosed town lands, and the monks, "armed only with spiritual weapons," held aloft a cross and evoked a curse in German and Arabic on those who intruded on their "sacred" ground!

The point at issue was, of course, whether the documents by which the monks claimed the land were legal, but that did not lessen the pity of the quarrel between two "religious communities," though such strife is, alas, too common in Palestine.

Travellers are always warmly welcomed at the monastery, in conformity with the old time traditions of hospitality, and it is a delightful place to stay a few days, being perched 500 feet above the sea on a spur of the mountains. No bill will be given to you when you go, but universal custom sanctions an offering in accordance with your means.

Among the mystics who have been drawn from their own land to Mount Carmel, the

[page 15]

brilliant gifted writer Laurence Oliphant, and his high-born, delicately-nurtured, lovely wife, who was content to labour at lowly household work varied with kindly ministrations to her humble neighbours for five long years, will never be forgotten.

The story of the Oliphants' life at Haifa is sympathetically told in the "Memoirs" written by Margaret Oliphant. After his strange meteoric career (in which place and power as a statesman and leader of all that was best in social life were sacrificed to a religious principle which bade him go and work as the meanest labourer in an obscure community in America and consent to years of separation from his devoted mother, Lady Oliphant, and his adored wife), the happiest years of Laurence Oliphant's life were spent at Haifa in a house in the German colony which is still pointed out. When you see it, reflect that "the whole soul of the two to whom the house belonged was bent upon leavening the world with a knowledge of the love of God . . . their

[page 16]

main object was to live a life like that of Christ in the world!" By birth, petted children of fortune, by early association, accustomed to the intellectual life of London and Paris, they were content with the society of the homely, kindly Germans and the love of "a little floating circle of friends and disciples who circled around them." Not a few travellers with names famous in Europe, made a détour to visit that idyllic home where the Oliphants lived the life that they believed was the manifestation of the highest truth, loving each other and all the world, and "going about doing good." Laurence Oliphant's first visit to Palestine was to report on sites for the Jewish Colonies, then about to be founded. During his residence there, he was ever ready to hold out the hand of friendship to the poor wandering Jews who landed forlorn strangers in the land of their fathers; but his biographer says it was "more what we call chance than any deliberate choice that directed them towards Haifa, a small

[page 17]

bright Syrian town lying on the western edge of the Bay of Acre, with a beautiful view across the bay of that historic fortress and the noble background of the hills of Galilee." Was it chance? Was it not rather the Divine Leader the Oliphants followed so unswervingly that not even the disillusion of finding the earthly leader they had half deified had feet of clay, could shake their faith, that led them to Mount Carmel?

All that was earthly of Alice Oliphant rests in the German cemetery at the foot of the sacred mountain, and men and women of diverse tongues and creeds have shed tears beside her grave.

Her death followed a trip to Tiberias, which she describes in the letters as "the happiest fortnight in my life," and was put down to the fever-laden air of the low ground by the lake where they camped. Almost it seems as if that sweet spirit had attained as near perfection as mortals can in this world and so passed on.

She breathed her last on the heights

[page 18]

of Mount Carmel, which had been her summer home, and the grief of the people of the adjacent Druse villages was intense. "If five of our best sheiks die village not so sorry!" they said, and when bearers were wanted to carry the corpse down the mountains to the road where carriages could meet the funeral cortege, fifty men vied for the honour, where only eight were needed. Two miles from the colony, all the principal men of the German colony, and all the foreign consuls and their dragoman and cavasses met the bier with many Arabs and a Moslem guard of honour sent by the Governor. "Had she been a queen," her sister wrote, "she could not have been received with more respectful homage — and it was all a spontaneous expression of love — personal love for her."

Does it not link modern life most wonderfully with Bible times, that the Mount of Elijah has ever been, and still is in these latter days, the home of saints and mystics who count the world well lost for God.

2. Image scans

|

|