|

|

Abstract: A study of the structure, development, space, and historic preservation of a portion of Akka, including discussion of its place in Bahá'í history. Notes: Thesis for the University of Pennsylvania Master of Science degree. This document is available in a variety of formats at archive.org. |

The Historical Development of Genoa Square in Acre Israel from the Seventh Century to the Present Day

by Amy Suzanne Hollander

pages 30, 40-43, 46, 54, 120, 124, 125, 1501995

[page 30]

DRUSE CONSTRUCTION

The city underwent its first reconstruction in 1595 when the Druse leader, Fahr ed-Din came to power. The first ruler since the Crusades to improve the state of the city, he added a customs house, a palace, a mosque, and began the reconstruction of the Hospitallers fortress. It was also during this time, according to 17th century travellers, that "Emir Fahr ed-Din restored the Church of St. Nicholas for the use of Europeans...with a choir and three naves of reasonable size. It is divided for the use of the Maronites and the Greeks, each one pressing a part."45 He restored this structure for the Christians he encouraged to settle in Acre. The Greek Orthodox Church of St. George in Genoa Square today corresponds in plan with the 17th century traveller's account of the Church of St. Nicholas, and it is believed to be on the same site of the Crusader Church of St. Lawrence. "It can hardly have escaped damage in the bombardments of 1831 and 1840 and must have been renewed in part, however, it contains portions of a carved and painted wooden sanctuary screen of Cypriote style of the 17th and 18th century, which was dismantled to make way for the present stone screen."46

The stylistic elements of this structure have almost no similarity to that of the rest of the square. Although the only religious structure, this does not account for the radical difference of its stylistic elements. There is a Byzantine angularity to the woodwork in the doors found only in two other doors in the square; that of the Bahai, and in one of the doors on the south facade of the square. ...

[page 40]

... In 1868 Bahá'u'lláh, father of the Bahai religion, was brought to the City of Acre as a prisoner for his religious activities. He describes Acre at this time as having:

Sunk, under the Turks, to the level of a penal colony to which murderers, highway robbers, and political agitators were consigned from ail parts of the Turkish Empire. It was girt about by a double system of ramparts; was inhabited by a people who Bahá'u'lláh stigmatized as the 'generation of vipers'; was devoid of any source of water within its gates; was flea infested, damp and honey-combed with gloomy filthy and tortureous lanes. According to what they say...it is the most desolate of the cities of the world, the most unsightly of them in appearance, the most detestable in climate, and the foulest in water. It is as though it were the metropolis of the owl. So putrid was its air that, according to proverb, a bird when flying over it would drop dead."63By 1870, due to overcrowding in the prison, the Bahá'u'lláh was released to house arrest in the city of Acre. Here he resided in Genoa Square until 1896 when he moved to a larger complex in the city.

THE BAHAI IN GENOA SQUARE

When released to house arrest the Holy Bahai family moved into a small town house in the Christian community in Genoa Square around the Church of St. George. The house had previously been owned by a wealthy Christian Merchant, Udi Khammar, who had just moved to a restored mansion two kilometer northeast of the city. This house was the smaller eastern part of a double house which faced Genoa Square, then Abbud

-

63. David Ruhe, Door of Hope: A Century of the Bahai Faith in the Holy Land (Oxford: G. Ronald, 1983), 24.

[page 41]

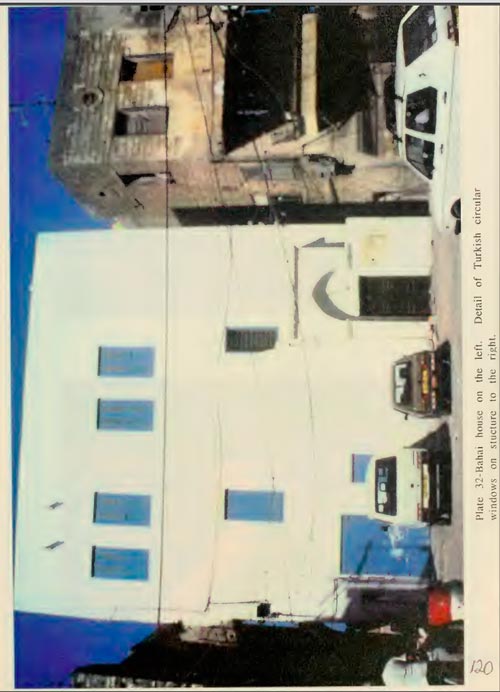

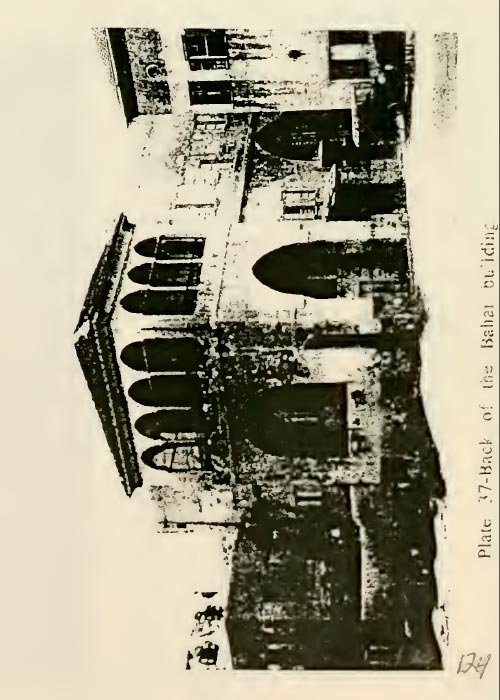

Square. (Plate 32 [see below]) The larger half of the house stood to the west, facing the sea, and belonged to Illyas (Elias) Abbud. (Plate 37 [see below]) These two houses were divided by, "a common wall...with the ground floor of both houses used as business premises. The holy family moved into the small house,...so insufficient to their needs that in one of its rooms no less than 13 persons of both sexes had to accommodate themselves."64

The Bahai were not immediately accepted into the Christian community. As political agitators they were viewed with suspicion and distrust. The slightest incident,

fired [the Christians] with uncontrollable animosity for all those who bore the name of the faith which those exiles professed...Abbud who lived next door to Bahá'u'lláh, reinforced the partition that separated his house from the dwelling of his now much feared and suspected neighbor. Even the children of the imprisoned exiles, whenever they ventured to show themselves in the streets during these days, would be pursued vilified and pelted with stones.65However, things settled down and in 1872, when the son of Bahá'u'lláh was to be married, Abbud "offered to provide a room from his own house for the master, furnished one which adjoined the little house on the top floor, opened a doorway into it through the dividing wall, and then presented the room to Bahá'u'lláh for the master's use."66 A greater freedom of movement was allowed to Bahá'u'lláh over the years allowing him to pass the word of his faith.

When Abbud decided to leave the city, he finally relieved the cramped space of the holy family, by renting them his half of the house. At this time, "a door way was broken

-

64. Ruhe, 189.

65. Ruhe, 43.

66. Ruhe, 45.

[page 42]

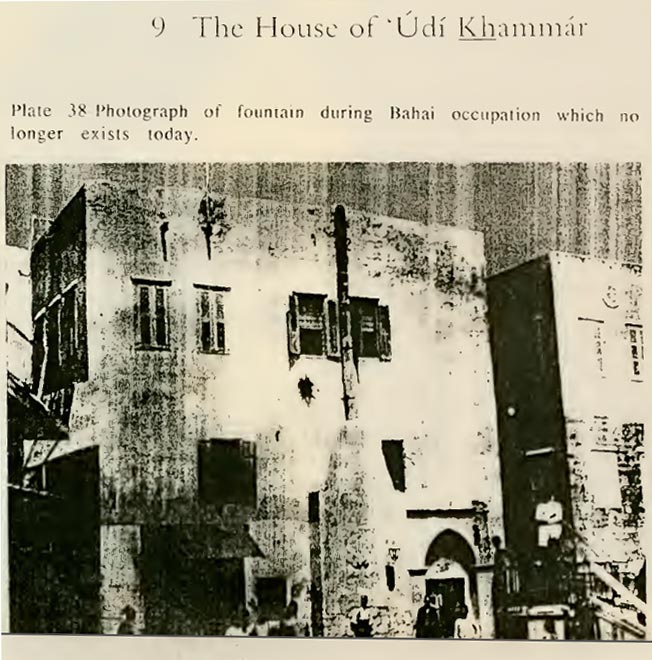

through the common wall, on the topmost floor, fusing the two upper courts, and on the ground floor a doorway was also cut for access between houses."67 Bahá'u'lláh, at this time, also began to rent a room across Genoa Square in the house of Tannus Farrah. His house fronts Genoa Square diagonally opposite to the House of Bahá'u'lláh. Even after his death, the House of Bahá'u'lláh was a place of pilgrimage for the followers of Bahai. A photograph shows the existence of fountain time as well which lay next to the house of Udi Khammar.68 (Plate 38 [see below])

Although no maps of Acre from the Bahai perspective were available for this study, a series of maps dating to the mid 19th century show that a monumental change in the geography of the square occured in this time. Pre-dating the Bahai period, both Lieutenant Col. Alderson's plan of Acre drawn in the 1830's (Map 6), and J. Kelly's map drawn for the Quarter Master General's Department in 1850 (Map 7) show two distinct squares at the study site. However, F.G. Lowick's plan of the city drawn between 1923-1925, shows a new layout for Genoa Square in which the two distinct squares have been combined. (Map 8)

The maps indicate that at this time a change had been made in the buildings to the west of the Church of St. George. What was once two buildings, facing so close to each other that only a small passage separated them, now was open, and two new structures replaced the originals. The consequence of this change is that the space to the west lost its rectangular shape and that, to the east, a square has been created in front of the church. The structure removed was, at least at its foundations, the original Genoa Gate of the Crusader period.

-

67. Ruhe, 46.

68. Ruhe, 39.

[page 43]

The disposition of the foundation walls generated the narrow passage between the two halves of the original structure. Its removal marked an age that no longer looked to fortification as a necessary criteria for building. New weapons and a new government made such structures and divisions of space obsolete in the Old City of Acre. Although we have not yet pinpointed the exact year of destruction or construction of these structures, we can reduce the span in question, by taking note of a comment mentioned in the Door of Hope about the residence of the Bahá'u'lláh who had rented a room in the structure in question before it was destroyed.69

The stylistic elements of the new structure built in its place are distinctly different than those of the other structures in the square. Instead of the horseshoe windows of the early Turkish period, the new construction uses three squared windows. (Plate 39) There are none of the circular windows found on other structures in the square. It makes use of a scraffito facade which can be described as a cement plaster which is decoratively scored. (Plate 40) However, unlike the complicated, all-over, abstract designs found scored in the stucco of other structures in Acre, the scoring here is very sparse and European, outlining the structural elements only. The feature of a clock is scored in the center of the facade, further drawing on European practice. (Plate 41) The central entrance of the building employs the Greek doric columns and entablature also prevalent in English architecture of this period. (Plate 42) These European stylistic preferences suggest that the structure was built after the British came to Acre (see below).

-

69. Ruhe, 223.

[page 44]

BRITISH OCCUPATION

In 1918, Acre was captured by the British. During the British Mandate, Acre continued to expand beyond the walls of the old city toward the north and east, serving primarily as a penal colony. It also began to flourish as an agricultural center for the growing population around Haifa during this time. Suburbs rose outside the walls, and the British provided better health, education, and administrative services. The British Mandate began to establish public services in Acre at this time as well. As the Arab National movement grew in this region, both the British and the Jews became increasingly unwelcome in the city. By World War II, few if any Jews or British were left remaining in the city. In his text, The Walls of Acre, Morton Rubin tells us that,

Modernization came slowly to Acre during the period of the British Mandate. Old Structures and institutions sometimes found new uses. For example, the camel caravan stops were converted into truck repair stations, metal workshops, and processing plants for tobacco and olive oil. Almost no trading vessels called at the port, but fishing continued and found a ready market in the district and among tourists. The mosques and churches remained centers for religious and communal life. The British continued the tradition of assigning family affairs to the jurisdiction of religious courts. The walls of Acre were breached in two places to permit motor roads between the Old City and the New City, which was expanding due to the growth of population and the effect of prosperity. From a 1922 official census record low of 6420 residents, the population had to risen to more than 15,000 during the period of World War II.70In 1945, Percy H. Winter developed a redevelopment plan based on city survey report for the Public Works Department of the Government of Palestine. (Map 9) In his survey of the Old City, Winter "counted 8500 residents with an average of 3.2 persons per room.

-

70. Morton Rubin, The Walls of Acre: Intergroup Relations and Urban Development. (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1974), 13.

[page 45]

Households averaged six or more persons, with several generations living under one roof. There was almost no town sewage, garbage disposal, or street repair service."71

MODERN HISTORY

In 1948 with the development of the Jewish State of Israel, the Jews took control of Acre, and at that time they adopted Winter's redevelopment plan as a part of their public policy. As thousands of Jews were relocated, the need became apparent for the establishment of new zones and the transformation of swamp and beaches into useable land.

In 1962 another survey was undertaken for the restoration of the Old City of Acre. Organized by city planner, Kesten, it emphasized the restoration and rehabilitation of the historic structures of the Old City which were falling into neglect. (Map 10) His survey analyzed population density and diversity, as well as the use, construction, and condition of the built structures. He devoted two maps to marking the archaeological remains of the Crusader city. He also noted the lack of modem utilities, and showed that sanitary facilities were almost completely lacking at this late date. Where bathrooms did exist there was rarely running water.

Today the Genoa Square shows a conglomeration of all its stylistic building periods. The streets in the square are not paved in the traditional sense. They are made up of large, flat stones of different shapes and sizes which have been used much like our cobblestone streets. (Plate 43) There are five entrances to the Genoa Square, only two of which are large enough for vehicles to pass through. (Plates 44-48) Trucks cannot pass through at all,

-

71. Ruhe, 13.

[page 46]

and large loads of supplies are still brought through on horse and cart. All the passageways which enter the square are roofed by arches and in the northwest and southeast corners have been completely covered by vaulted passages. The buildings overlap each other, and often entrance to one can only be gained by crossing through another structure. The discrete squares known from Crusader times have been opened onto each other with a wide road between the north and south faces of the square. (Plate 49) The open spaces of the square serve mostly for parking, and children's play. Two general stores are found in the Genoa Square. The church is still in use as is the Bahai house of worship. The rest of the structures are used for residential purposes. A pita bakery lies just off the square. Those original first floor shops and stores are used today mostly as people's homes. The interior courtyards of the structures are intact, and it is in these spaces that the Muslim women interact. The Christian women are seen far more often in public out in the square.

[page 54]

TURKISH. In 1862, The Bahá'u'lláh notes that a structure of some sort still stood on this spot, while maps from the second decade of the twentieth century show that it had since been destroyed and replaced with a modern structure. Many elements of the new structure have been realtered in more recent times, however, on the facade, four examples of the original wooden windows and frames can be found on the second floor western half of the structure. The arched windows which are found on the second and third floors of the building also date to its original construction. It is most likely that the cement plaster on this structure is original to its construction. It is interesting to note a European influence on the architectural details of this structure. The columns framing the front entrance are not found elsewhere in the square. Neither is the scored plaster. Typical scoring of plaster in Acre follows the Omayyad tradition of overall ornamental design. Here we see a subtle outlining of architectural features which resembles a more European technique of plaster scoring. The wooden door on the western face of this structure is also an original feature. ...

[page 120]

click for larger image

[page 124]

[page 125]

[page 150]

32. Color Xerox of Bahai House. Turkish Circular Windows on Structure to the Right.

...

37. David Ruhe. Photograph of Back of the Bahai Building. Door of Hope: A Century of the Bahai Faith in the Holy Land. (Oxford: G. Ronald, 1983).

38. Ruhe. Photograph of Fountain during Bahai Occupation which no longer exists today.

Image scans

For other maps and photographs, see the document online at archive.org.

|

|