|

|

Abstract: Co-authored/painted paper by Aboriginal and 'Western' authors primarily focusing on spiritual issues in law. Notes: Originally presented at Washington University, International Conference, April 2003, "Biodiversity and Biotechnology and the Protection of Traditional Knowledge". Mirrored at Wash. Uni. Law School: law.wustl.edu/centeris/Confpapers/ |

Bioprospecting and Indigenous Knowledge in Australia:

Implications of Valuing Indigenous Spiritual Knowledge

by John Hunter and Chris Jones

2006-07Introduction:

This chapter discusses issues associated with

the capacity of western law in understanding and protecting indigenous

knowledge related to the bioprospecting of indigenous medical knowledge in an

Australian context. More specifically the focus is upon indigenous spiritual

knowledge. It is suggested that central to this project is the right of

indigenous peoples in self-determination, self-identification and the right of

verifying the authenticity of representations about such knowledge.

The Julayinbul Statement on Indigenous

Intellectual Property Rights (1993), originating from an Australian

Indigenous conference in Jingarra states:

Indigenous Peoples and Nations share a

unique spiritual and cultural relationship with Mother Earth which recognises

the inter-dependence of the total environment and is governed by the natural

laws which determine our perceptions of intellectual property.

Inherent in these laws and integral to

that relationship is the right of Indigenous Peoples and Nations to continue to

live within and protect, care for, and control the use of that environment and

of their knowledge.

Within the context of this Statement

Indigenous Peoples and Nations reaffirm their right to define for themselves

their own intellectual property, acknowledging their own self-determination and

the uniqueness of their particular heritage.

Within the context of this Statement

Indigenous Peoples and Nations also declare that we are capable of managing our

intellectual property ourselves, but are willing to share it with all humanity

provided that our fundamental rights to define and control this property are

recognised by the international community.

These concerns require a genuine consultation

between cultures. This is not only reflected in the subject matter of this chapter,

but also in that the chapter is co-authored in a research relationship between

an indigenous author and an author of Western cultural background. The

indigenous author (Hunter) also created and presented a painting in the

conference co-presentation prior to the reading of this chapter. The

sophistication and multiple levels of knowledge represented in the painting

represent a comprehensive system of indigenous knowledge that would take a

number of years of education to appreciate. Although it will not be immediately

obvious to western viewers of the painting, it actually represents a more

comprehensive expression of knowledge than this chapter itself.

Such a context is also symbolic of discussions

in the chapter about the capacity of law in general and Intellectual Property

Rights (IP) specifically to understand and protect indigenous spiritual

knowledge.

It is valuable for persons from western contexts

of law to become concerned with the building of bridges between cultures that

is required in such a process. Enduring bridges appropriate to such a

relationship require the infusion of a number of spiritual virtues including

humility, integrity, patience, transparency, respect, and trustworthiness.

These spiritual principles must be applied in a framework honouring the sacred

obligations associated with becoming a custodian of particular forms of

knowledge.

On a material level, those concerned with

building economic bridges through which valuable transfers of knowledge can

occur should be ultimately concerned with ensuring such spiritual concerns of

indigenous people are considered and applied. The degree to which this is

authentically engaged will determine the degree to which indigenous communities

feel confident in sharing their valuable knowledge across that bridge.

Alternately, many indigenous peoples feel a sacred obligation to respect the

sources of that knowledge to the degree that they would prefer letting it ‘return to the earth and the spirit world’,

rather than be misused and denigrated. For indigenous people the apparent

physical loss of such knowledge does not mean it is gone forever. Such

knowledge will continue to exist in the invisible world, hidden from the eyes

of all, until people of respect and wisdom are found worthy enough to be given

its gift again.

The ultimate benefit of a genuine engagement

with indigenous peoples and their knowledge represents a great gift to

humanity. It is argued that this represents the greatest opportunity for the

creation of a legal and social culture that manifests a true ethic of

ecologically sustainable development, and is essential for the survival of the

human species.

History of Bioprospecting and the Genocide of

Indigenous Culture

“That [people] do not learn very much from the

lessons of history is the most important of all lessons that history has to

teach.”

-Aldus Huxley

In our attempts to formulate appropriate

intellectual property laws for the protection of indigenous knowledge it is

easy to be distracted by the apparent technological novelty of modern

biotechnology industries and “sudden” awareness of the enormous economic value

of bioprospecting in our modern context. Often one gets the impression in

current literature that bioprospecting is made possible by recent increased

capacities in the biotechnology industry and often the focus is upon the nearly

exponential growth rates in patenting activities (Reid 1994) and economic

growth.

The reminder that history repeats itself (and

that we often forget such repetition and thus fail to learn from it) is

valuable for our discussion in our focus upon the “new” industry of bioprospecting

and the appropriation of indigenous knowledge. The collective memories of

indigenous peoples are often long and tell a different story.

Bioprospecting is one of the oldest industries

in the history of civilisation. Every civilisation has been dependent upon the

extent to which they developed knowledge of their biological resources and to

what degree they sustainably used that knowledge in supporting their needs of

agriculture, medicines, and other industries. Equally so, unsustainable bioprospecting

practices and the manner in which those resources were unsustainably exploited

played no small part in the demise of a number of great civilisations and is a

watershed moment upon which our own civilisation now faces.

The appropriation of such resources from

indigenous peoples by the dominant cultures has also been an ancient part of

this industry. It has been said that Christopher Colombus was, among other

things, an archetypal bioprospector in search of the East Asian “Island of

Spices” who instead found a Caribbean island and began a familiar process of

transferring the countless genetic resources from indigenous peoples to the

developed nation states of Europe (Auer 1998). Accompanying this “transfer” of

intellectual property is something far more sinister than mere issues of

ownership and theft.

Within decades

after the ‘discovery’ of America, whole nations which had thrived there for

centuries had been reduced to nothing. Millions of men, women and children were

massacred. Those who survived suffered untold misery and deprivation. The

conquerors, while eliminating the indigenous people, also introduced African

slavery on the continent. History

can be re-written. It cannot be undone...five centuries after Colombus,

[indigenous peoples] cause [is] still not being taking seriously. (ICIHI 1987)

This is not an appeal to historical injustice to

garner moral appeal for more comprehensive intellectual property rights as a

manner of restitution for past injustices. The value of acknowledging this in

current IP discussions is for a number of reasons. First it is to remind us of

the accompanying contexts of indigenous genocide that inevitably become

associated with such “transfer” processes. While such appropriation may not in

itself cause the cultural genocide, it is symptomatic of the overall

objectification and devaluation of the subordinate indigenous cultures by the

dominant cultures which is the primary cause of such cultural genocide. Such

historical patterns of genocide are not footnotes in an elementary school-book

but are very real present-day realities. UNESCO reports that 4,000 to 5,000 of

the 6,000 languages in the world are spoken by indigenous peoples (UNESCO

2003). 2500 of those indigenous languages are under immediate threat of

extinction in the present generation, and it is also estimated that 90% those

indigenous languages that make up the majority of the worlds cultural diversity

will become extinct in the next 100 years (Skutnabb-Kangas 2000).

Acknowledgment of the interdependence of the

link between cultural appropriation and cultural genocide is important to IP

because ultimately it reminds us of the true gravity and importance of our

discussion in that the implications of a wise focus include not just the

protection of unique knowledge, but the very protection of human lives and

communities. This naturally leads to the second value for IP discussions in the

recognition of integrated indigenous needs. Such recognition supports the

movement towards integrated legal regimes of IP, Human Rights, and

Environmental Law, that don’t just protect the knowledge of indigenous peoples,

but protect the indigenous communities themselves and allow the capacity for

self-determination that ultimately facilitates the preservation of such

knowledge.

The undisclosed global value of Indigenous

medical knowledge

A commonly accepted estimate in the literature

indicates that a full 77% of all plant related pharmaceutical products

(Farnsworth et al., 1985), or roughly 25% of the entire pharmaceutical market

(Duke, 1993) contains significant elements of direct contribution from the

appropriation of indigenous knowledge. The figure of 77% becomes even more

significant when one considers that the World Bank recently estimated that

plant related medicinal products would reach a global value of US $5 Trillion

dollars by 2050 (Gupta 2004). Apart from modern pharmaceutical usage,

traditional systems of medicine and alternative and complementary medicine

represent up to 50% of use in many industrialised countries and up to 80% in

many developing nations (Bodeker G. and Kronenberg F, 2002). Combining the

indigenous contribution to pharmaceutical medicine with its traditional use

world wide indicates that indigenous knowledge may be responsible for over 60%

of medical treatment in developed nations and 85% in developing nations.

Bioprospecting in Australia: The unregulated

gold rush

Against this global context it is important to

note that Australia possesses greater potential for productive bioprospecting

than any other developed nation in the world. This is due to its high levels of

endemic biodiversity that place it 1st among developed nations and 6th globally

on the National Biodiversity Index, (UNEP, 2001) while this biodiversity is 90%

endemic. (Beattie 1995) Combine this with its equally high level of Indigenous

cultural diversity, and the potential for the exploitation of Traditional

Knowledge in facilitating the bioprospecting industry becomes apparent.

The appropriation of medical products and

knowledge of indigenous people in Australia has a long history that predates

British colonisation. One of the earliest examples that we have goes back to at

least the early 1600s, with the trade in trepang (also known as Sea Cucumber).

Macassan fishing boats from Indonesia brought fishermen to the northern

coastline of Australia searching for trepang.

This was traded and sometimes fought over with

Indonesian merchants who would then sell this delicacy to the Chinese market.

Among other uses, it was dried and used for its numerous medical properties,

including reduction of athralgia, atrophy of the kidneys, impotence, and many

other medical uses (Dharmananda S). Most recently Japan

has patented a compound from the Sea Cucumber, chondroitin sulfate for HIV

therapy (Kariya et al., 1990). Modern research is also focusing on its

anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties.

One

of the first examples of post-colonial bioprospecting activity is recorded from

the 1870s when

Dr Bancroft, a Brisbane surgeon, used the

knowledge of the Aboriginal peoples to substitute extracts from the Dubosia plant as a

substitute for atropine in opthalmic cases. The plant was also found to contain

hyoscine, used as a sedative, in the Second World War, a local Dubosia industry was

developed, as imports of these drugs were unavailable. By the 1970s there were

some 250 farmers growing Dubosia in northern New South

Wales and southeast Queensland, with an export industry worth more than Aus$1

million annually. Other than in employment, the traditional users of these

plants have received no tangible benefits. (Blakeney M, 1997)

More recently, in the 1980s the United States

National Cancer Institute was granted a license to collect plants for screening

purposes by the Western Australian Government. A healing plant traditionally

used by the Nyoongah people, the Smokebush (Genus Conosperum), was found to

contain the bioactive compound of Conocurovone, which is capable of destroying

the HIV virus in low concentrations.

The

NCI sought further samples and a licence to collect more samples in Western

Australia. The Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) attempted

unsuccessfully to negotiate a contract with the NCI (Janke & Quiggan 2005).

When

after four months or so had gone by and there was no contract agreed between

Western Australia and the NCI, the collector attempted to leave the country

with the samples. He was found at Tullamarine airport with two of his three

cases full of smokebush and other plants” ((N Marchant, C Bailey and J Cannon

reported these events in M Parke and C Kendall, ‘Bioprospecting of Traditional

Medical Knowledge’ (unpublished paper, Murdoch University School of Law, Perth,

1997, Cited in Janke and Quiggan (2005).

The license to develop the patent on this

"discovery" was awarded by the US National Cancer Institute to Amrad

who paid $1.5 million to the Western Australian Government in order to obtain

access to the Smokebush and related species. It has been estimated successfully

commercial exploitation of this plant may represent over $100 million per year

in royalties to the WA Government (Blakeney 1997). "Indigenous people are

concerned that they have not received any acknowledgement, financial or

otherwise, for their role in having first discovered the healing properties of

Smokebush." (Janke 1998)

It is interesting to note that while subsequent

information in 2005 appears to indicate that this particular medicine was

‘shelved’ under the claim that clinical trials found it to be neurologically

toxic in the oral method of treatment developed by AMRAD.

Dr Gregg

Smith, an

Australian biotech scientist at AMRAD, who after expensive phase one testing

and scientific dead-ends, was forced to shelve research with Smokebush’s

synthetic compound concoverone. Known as a clunky compound, Smokebush’s

concoverone is apparently too robust and cannot be broken down or ingested

safely by humans infected with HIV (Williams).

It is reported that an executive in AMRAD has

admitted that at no time did they consult with the original community to

discuss Nyoongah preparation methods or drug application and did not want to

listen to any information related to demonstrating the indigenous source of the

medicine when offered a description by the interviewer (Williams). In this case

one could surmise it may have not only assisted in appropriate benefit sharing

protocols, but possibly made a significant difference to the success of the HIV

medicine as the Nyoongah people utilized the plant through different

preparation processes and a final inhaling application rather than ingesting it

orally which AMRAD developed separately. This highlights the lack of

consultation processes between the bioprospectors, government institutions,

pharmaceutical representatives and the indigenous community members and the

possible loss to society this may have caused. It seems from initial interviews

that the local community members are completely unaware there were even major

research and development projects involving their original plant knowledge

(Williams).

Another case is the Muntries plant which is like

a miniature apple:

Muntries is a native

plant that’s well-known to local Aboriginal people; they ate the fruits and

dried them to trade with other tribes. In 1996 provisional plant breeders’

rights for muntries were granted to a company called Australian Native Produce

Industries. By taking this native plant and breeding it, the company obtained

the exclusive right to use this cultivated species of the plant in commercial

products. Muntries chutney is now sold at Coles supermarkets, part of the range

of indigenous food products that has generated over half a million dollars in

sales in its first year on the market (Watson I, 2002).

Some suggest the company never actually

undertook genuine plant breeding but simply submitted an ‘original’ version of

the plant (HSCA 1998). It is interesting to note that according to IP

Australia’s database the application for Plant Breeders Right of the Muntries

was withdrawn in September 2004.

In

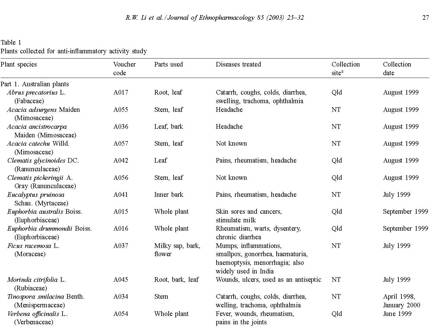

Australia there are a number of books which have been compiled to record the

ethnobotanical medical knowledge of Aboriginal peoples. The sample table below

lists a range of plant material collected for analysis and the traditional

Aboriginal medicinal uses associated with the plants.

Table

1.2 (Li 2003)

click for larger image

There are many other examples of Australian

Indigenous medical knowledge reflected in scientific research that cannot be

necessarily linked as specific examples of bioprospecting. Sometimes there is a

genuine parallel and separate research 'discovery' that coincidentally was

already known to Indigenous people. For example there are patents pending on

powerful anti-biotic compounds secreted by the metapleural gland of the

Australian Bull Ant. This was a recent discovery by Australian scientists.

However, Aboriginal Australians have known about the anti-biotic property of

this Bull Ant secretion for generations (Beattie 2001). Professor Andrew

Beattie related to the author how an Aboriginal woman in Central Australia

heard an interview of his on the radio about the anti-biotic properties of the

Bull-Ant and phoned him with excitement to confirm her mother used to treat her

and her siblings. She described a process where they would stir up a Bull Ant

nest, wrap a cloth around a stick, push the cloth into the nest until it was

covered with ants, pull it out and shake off the ants, and then bind a wound so

that it would not become infected in the hot desert sun. She was excited

because the radio interview confirmed the knowledge of her mother and ancestors

about the antibiotic properties of the ant secretions used for generations by

her community.

The background of regulation related to bioprospecting

in Australia

Indigenous medical knowledge (IMK) requires

protection within a number of legal regimes for such protection to be

effective. These include environmental law, intellectual property law, human

rights law and an increased capacity for self-determination through a more

comprehensive recognition of native title and accompanying land rights.

Nationally uniform legislation that positively

and directly protects IMK in Australia does not exist. There are a number of

inhibiting factors to overcome for this to change, while equally there are

positive signs that such a capacity is developing.

In

1996 a policy document was released, the National Strategy for

the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity (DEH 1996). Of significant

note is that section 7.1.1.b of the document outlines the goals for the

implementation of the strategy and indicates a commitment within four years to

developing ethnobiological programs that not only ensure cultural continuity

but results in benefits of social and economic development to Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples:

Actions

7.1.1 Priorities and time frames

By the year 2000 Australia will have:

- completed the identification of its biogeographical

regions;

- implemented cooperative ethnobiological programs, where

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples see them to be appropriate,

to record and ensure the continuity of ethnobiological knowledge and to

ensure that the use of such knowledge within Australia’s jurisdiction

results in social and economic benefits to Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples;

In

May 1994 Australia established a Commonwealth State Working Group on Access to

Biological Resources to investigate options for a national approach to access

to biological resources in Australia. The goal of the Working Group was to

identify the benefits of a national approach for the Australian community, to

develop principles to be applied in the assessment of mechanisms and in

negotiations concerning the grant of access, and to develop mechanisms that may

be employed to govern the access to and the collection, processing, development

and export of Australia’s biological resources. The Working Group then produced

a draft discussion paper which considers arrangements for managing access to

Australia’s biological resources, and proposes a nationally consistent approach

(Hassemer 2004).

In 2002 the Federal government’s released

its most recent policy paper in the area, ‘Nationally Consistent Approach For

Access to and the Utilisation of Australia's Native Genetic and Biochemical

Resources’ (DEH 2002). It indicates its commitment to fulfil its obligations to

the CBD and includes reference to principles of particular relevance to Australian

Indigenous peoples:

-

enable the fair and equitable sharing of benefits derived from the use of

Australia's genetic and biochemical resources;

- recognise the need to ensure the use of

traditional knowledge is undertaken with the cooperation and approval of the

holders of that knowledge and on mutually agreed terms;

- be developed in consultation with

stakeholders, indigenous peoples and local communities;

This national policy is the clearest commitment in Australia

to principles of the CBD, including equitable access and benefit sharing,

mutually agreed to terms and prerequisite consultation processes with

indigenous communities. However such positive

policy shifts have yet to demonstrate effectiveness in influencing relevant

legislation or related Native Title issues.

Commenting on the Nationally Consistent Approaches in

general, a government officer working for 25 years in the areas of indigenous

affairs and the environment advised in personal correspondence in early 2006:

An NCA that is "positive" means everything to

everyone, like motherhood and apple pie.

I regret to say that some aspects of the current NCA discussions are actually

retrograde rather than positive. Anything that forces a Western cultural norm

on indigenous people against their will, requires careful examination. Forcing

a "One-size-fits-all" Western cultural norm is now the policy norm,

supported by a societal mood that is less tolerant of differences than 20 years

ago. Policy directions also favour immediate individual benefits rather than

stored/reserved communal benefits.

Even lumping all indigenous people across this continent together is a

potentially false premise. It is like saying the requirements of the Saami of

Finland are the same as for the Turks in Edirne (a comparable range of cultures

in a comparable sized continent).

Another classic fallacy is to equate the situation of tribal indigenous people

with those that have suffered "de-tribalisation" (similar to

confusing Afro-americans with other black Africans, leading to the current

situation in Liberia). The former tend to prefer collective benefits while the

latter are now calling for personal returns on royalties, with the associated

arguments about distribution between individuals, families and tribal groups.

I am also wary of highly educated, vocal individuals representing the silent

and even confused majority. The former are all influenced by their personal,

often regional, experience and quite often biased (either for or against

certain issues) by their Western education.

To me the degree of "lumpability" (aggregation of indigenous

concerns) is proportional to the level of abstraction up the hierarchy of

issues - the higher the abstraction the more relevant an NCA is, e.g.

principles of equity and access to resource benefits can be agreed as an NCA

but how it is applied in Central NSW and Arhemland may be entirely different.

The only sure principles [are] where every individual

matters (with their own specific requirements), ever community matters (with

its own local, environmental requirements) and people matters (with their

culturally-specific requirements).

The Convention on Biological Diversity has established a

national reporting process to monitor nation states implementation of the CBD

principles. In late 2005, the Australian Government released its third report

to the Convention on Biological Diversity (DEH 2005). While in that report

there is a series of mandatory questions.

What is of particular note here is that the NCA is offered

in this report of compliance to the CBD as an example of policy that has

created an environment where

Individual Australian jurisdictions are progressively

rolling out legislative and administrative measures to implement this

Agreement. For example, the Australian State of Queensland introduced the Biodiscovery

Act 2004 (QLD)

As is more fully explored below, the Biodiscovery Act 2004

(QLD) is perhaps the most notoriously cited example of ignoring indigenous

rights or obligations to international agreements such as the CBD, particularly

regarding such issues as equitable benefit sharing. The drafters of the bill

originally included reference to a questionable level of benefit sharing with

Australian Indigenous peoples, but withdrew any reference at all prior to it

being accepted as legislation. In that context, for it to be offered as an

example of Australia fulfilling its CBD obligations, particularly in the

context of ‘prior informed consent’ and ‘mutually agreed to terms’ with

indigenous peoples brings into question the actual effectiveness of the NCA in

effecting positive change in actual legislation.

The two primary IP regimes

associated with the protection of IMK are Patents and Plant Breeders Rights. In

2002 in Australia the Plant Breeders Rights Act (PBRA) was amended partly in

response to international obligations arising from the 1991 revised International Convention for

the Protection of the New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) which is related to TRIPS

issues of regulation. There was significant debate in the parliament about

including amendments that would acknowledge indigenous rights and reflect

obligations arising from the CBD, in particular article 8j. There were detailed

proposed amendments drafted by Senator Cherry which were discussed, for

instance issues of Prior Informed Consent, but most of which were not adopted. s64 (1)(f) was the only

significant amendment adopted, other than a definition of ‘indigenous’ inserted

in s3. s64 (1)(f) allows for a member on the National PBRA Committee who represents

indigenous interests. They may or may not be indigenous. The current member,

Professor Roger Leakey is not indigenous, nor have any indigenous people been

consulted in his appointment. The committee can only advise the Minister upon

his request. Originally Professor Leakey writes that

[I] applied to join PBRAC as an individual interested in

helping indigenous communities to domesticate Bush Tucker and to protect their

cultivars. I was then appointed as the member representing indigenous interests.

As I did not have the support of indigenous communities or any official mandate

to do this, I was somewhat concerned about this and insisted on an amendment of

the minutes of the first committee meeting that I attended, to clarify my

position. (Personal communication between Roger Leakey and Natalia D'Morias,

October 2005, cited with his permission and on file with author).

As of 27 March, 2006, IP Australia’s website still lists

Professor Leakey as the ‘Member Representing Indigenous Interests’.

Intellectual Property Law as it stands now

within Australia has generally not developed out of consultative frameworks of

policy or principles that rely upon the positive resources of international

conventions. (Such as the CBD, ILO 169, Human Rights Conventions, the UNESCO

Convention of Cultural Property, Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, CITES and the

Convention to Combat Desertification.) The standard of policy development has

been an ad hoc basis that has resulted in a less than satisfactory context,

particularly in regards to the protection of Indigenous Knowledge and the

potential implementation of appropriate national standards.

While Australia is a signatory to both

conventions [Berne & Paris], our intellectual property laws do not accord

protection to all the subject-matter referred to in these definitions. Nor do

they extend protection on the basis of some wider general principle that may be

readily and immediately applied to new kinds of subject-matter as they come

into existence. Our approach has been piecemeal, giving protection on an ad hoc

basis as new claimants have been successful in pressing their cases before the

courts or legislature. (Ricketson 1994)

There is a clear danger of developing IP for the

protection of indigenous knowledge upon such an ad hoc basis, rather than upon

a consultation process that results in commonly agreed principals that should

form the basis and guide the goals of such IP development. The danger is that

such a context correspondingly results in an uncoordinated application of

protocols of access to indigenous knowledge that will vary in their level of

ethical standards. More specific limitations of IP in protection IMK will be

discussed later in the chapter.

Lastly it has been argued that the most

comprehensive remedy for the protection of IMK are the positive development for

Indigenous land rights. The first recognition of native title in common law was

established in 1832 in the United States case Johnson v McIntosh. The

foundation of this recognition of native title was based on a 1537 Papal Bull:

[T]he said Indians and all other people who may later be

discovered by Christians, are by

no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property.

The 1832 decision of Johnson formed the

foundation of jurisprudence in New Zealand and Canada, while the Privy Council

has long acknowledged its authority.

Only since the 1992 High Court decision of Mabo (Mabo v

Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1) has the Common law principle

of Native Title been recognised. Yet the form that Native Title has taken thus

far is very limited in its scope in comparison with other common law countries.

Since 1996, further exacerbating such minimal recognition of indigenous land

rights, is the abandonment of Federal commitment to self-determination of

indigenous peoples. This former official policy of self-determination has been

replaced by a policy of 'self-management' in consultation with government

agencies. Equally the policy of reconciliation that had gained such momentum

until 1996 was abandoned and replaced with a policy of 'practical

reconciliation'. This effectively focuses on equality and unity (which some

have criticised as guises for assimilationism) but effectively ignores or

minimilizes historical contexts of unique discrimination. Thus the creation of

positive discrimination instruments for indigenous peoples through the creation

of any special rights is no longer an option in such a policy.

Due to this, the current political culture is

not conducive to using current capacities within Australian law to create any

special recognition of IMK.

It is this context in which Australia “won” the

highly uncoveted “Captain Hook” award from the NGO RAFI in 2000, for the

country engaged in the greatest levels of biopiracy in the world. This was

awarded "for over 118 dubious claims and possible piracies and for

refusing to address its intellectual 'meltdown'" (RAFI 2000). An

independent investigation into these claims by the President of the Heritage

Seed Curators Australia, confirmed that

In fact I quickly found that the

situation was far worse. Over the course of 5 months investigation we

discovered over 100 illegitimate PBR grants. In addition to plant varieties

from poorer overseas countries, there are many Aboriginal plant varieties that

have been appropriated via the PBR grant process. (Hankin 2002)

Generally, this context of ‘biopiracy’ is not

symptomatic of an institutionally organised attempt at such appropriation nor

any particularly conscious malicious intent. Rather it is primarily

representative of a largely unregulated industry that has resulted in a number

of parties seeking genetic resources from indigenous communities, whether

directly or through accessing public knowledge, without reference to a much

needed set of nationally standardised ethical guidelines that ensure

appropriate IP protocol.

While one is hopeful about the potential for the

CBD and other positive international forms of soft law to offset the conditions

that led to the endemic condition of biopiracy recognised in 2000, one can

anticipate a time lag in the implementation of the development of such national

policies on the local practical level where such appropriation continues to

occur. This positive potential is also mitigated by the commercial interests of

the nation in developing the bioprospecting industry, as seen in the recent

parliamentary inquiry: Bioprospecting: Discoveries Changing the Future,

(Inquiry into development of high technology industries in regional Australia

based on bioprospecting), August 2001. This document offsets CBD concerns by

emphasising the need to attract investment by reducing any appearance of

restrictive protocol or benefit sharing ‘barriers’. Section 3.49 acknowledges

that no provisions exist for benefit sharing arising from use of resources.

Current government interest is primarily upon

the facilitation of the biotechnology sector in order to potentially achieve

rapid economic growth. This is accompanied by both a national campaign to

develop biotechnology infrastructure, as well as aggressive international

marketing campaigns designed to attract multi-national interest in investment.

Protection of the environment is seen as necessary to the degree that it

facilitates this commercial activity. Ensuring correct protocol with indigenous

communities is seen as necessary to the degree that it facilitates the flow of

commercially valuable knowledge from indigenous communities to the

bioprospecting sector. Yet even this minimalist economic instrumental approach

is undervalued when legislation such as the Biodiscovery Act 2004 (QLD) is brought to

the table with no mention of appropriate indigenous protocols or benefit

sharing.

However, even from a

purely economic instrumental approach, there are good regulatory arguments for

reform that have not seen much discussion in Australia. For example on the

purely economic side of intellectual property and incentive theory, there are

at least two incentives to having special (sui generis) protection

for Indigenous intellectual property.

1) The incentive effect

to reveal the knowledge, (Because the Indigenous communities feel assured by

the special protection afforded their knowledge) thereby reducing the cost of

acquiring it, and

2) the incentive effect

to keep the knowledge pool in its entirety (Sempath 2005).

A full and frank consultation about these

regulatory principles would possibly be fruitful, however anything less than a

wide ranging and public consultation process can prove to not only be

ineffective but possibly harmful. For example, John Henry Vogel examines the Queensland

Biodiscovery Policy Discussion Paper (Queensland Government

2002), [where] the word “biopropsecting” has been replaced with the seemingly

less odious term “biodiscovery.” (Vogel 2005) Among various criticisms of this

discussion paper Vogel examines is the effective benefit sharing equation 0.003

or 0.3% on offer. While this is considered unreasonably inequitable in light of

the CBD, it also only applies to landowners upon whose land a 'biodiscovery' is

made, which removes indigenous people from such considerations of benefit

sharing even further. Of great significance is that the disclosure by Vogel of

this ‘backfired’ and the Queensland Government ended up removing altogether any

reference to benefit sharing with indigenous peoples rather than reform the

policy to meet the growing international standards (Vogel 2006).

There has been an explosion of biotech companies

formed in Australia in the past five years. In 2002 there were only about 180

biotech companies while by 2004 there were over 400. An increasing share of

them are dedicated to human therapeutics, the biotech field that includes the

bioprospecting industry, with a growth from 43% of the biotech sector to 46% in

February 2005 (DITR 2005). Nearly all of them are small to medium sized

companies. Those companies specialised in bioprospecting are focused on the

screening of flora and fauna for bioactive compounds. However they generally do

not continue to the final commercial stages of product development, marketing

and sales to the public. Once the isolation of the bioactive compounds has been

completed, the rights are sold to multi-national pharmaceutical companies,

usually based in the U.S.. Thus, although there is a national intention to

facilitate the biotechnology sector for its development as a significant

economic resource base of the country, in reality the current state of affairs

is enhancing the flow of genetic resources from the “South to the North”,

making fulfilment of the nations concern for truly long-term sustainable

development practices on a national level very problematic. Due to the current

awareness of economic loss associated with benefit sharing and the potential

undesired complexities associated with indigenous protocol issues,

bioprospecting companies in general prefer to develop and rely upon existing ex

situ

databases that do not impose such requirements. As indigenous knowledge that

has already been appropriated by such pre CBD ex situ collections

is not protected, this also makes it expedient as a valuable resource.

80% of all companies that use

ethnobotanical knowledge...rely solely on literature and databases as their

primary source for this information. This fact has significant implications for

benefit-sharing, and suggests that academic publication and transmission of

knowledge into databases - rather than filed collections on behalf of companies

- are the most common route by which traditional knowledge travels from a

community to the commercial laboratory. Companies therefore have access to

knowledge in ways that do not trigger benefit-sharing (ten Kate 1999).

It is also suggested that a significant amount

of undisclosed direct in situ appropriation of indigenous knowledge is

occurring in Australia. This assumption is justified for a number of reasons.

The first reason has already been mentioned, that of the year 2000 RAFI

“Captain Hook” award for the greatest level of biopiracy of any country. This

assumption is also due to the awareness of the cost savings associated with

bypassing much of the pre-screening processes associated with more random

methods. Currently there is little recourse for indigenous communities and

without well-designed pre-screening contracts, no penalties for unethical appropriation

are imposed upon corporate appropriation. The assumption of continued ‘black

market’ bioprospecting is further reinforced by the examination of the

statements of randomly selected bioprospecting company policies, quarterly

shareholder reports and annual reports which usually fail to mention any

indigenous participation whatsoever. Given that previous analyses has shown

that 77% of the bioprospecting of plant-related pharmaceuticals finds its

origin in indigenous communities, it is contrary to common sense to assume that

such a pattern has altogether ceased.

There is a growing consensus among indigenous

communities that IP as it currently exists in Australia does not sufficiently

provide effective protection for indigenous knowledge. As such one can anticipate

that in situ bioprospecting activities involving indigenous communities

will slow in coming years until indigenous confidence in the effective capacity

of IP is restored.

The next section of the chapter addresses some

of the background concerns of indigenous people, the nature of indigenous

knowledge, and suggests ways forward in the long term process of determining

how it can be protected in order for relationships of trust to be justifiably

developed.

2. Indigenous concerns related to the protection

of Indigenous Knowledge

It should be first stated that this by no means

represents a comprehensive overview of indigenous concerns. Rather it is an

attempt to take a step back, allow a wider vision of context, and then discuss

select concerns that are considered under-represented in the IP debate. This is

offered as resource for addressing more fundamental long-term issues of IP, but

are considered no less important than many of the necessary and immediate

attempts of remedy involving more specific technical discussions.

Avoiding objectification

First it is important to recognise something

that seems like common sense but that occurs remarkably frequently in our

history. It is that we should avoid objectifying the thousands of unique

indigenous communities or their knowledge systems as monolithic singularities

whose nature can be simply categorised into neat definitions. Due to the great

diversity of contexts that indigenous peoples experience, the qualities that

comprise their community identity will vary widely. As well, their knowledge

systems are equally diverse and are highly complex metaphysical networks of

concepts that manifest themselves in a great variety of methodological

applications suitable to the particular ecological contexts in which they

dwell. In order to avoid such errors of simplification, misrepresentation and

distortion of diverse identities and knowledge systems, it is suggested that

development of appropriate IP laws is entirely dependent upon wide ranging

consultation with such communities. This also implies the need for recognising

the importance of indigenous self-determination in that it is they who are the

experts in advising what is indigenous knowledge. All to often our laws have

sought to inappropriately define what is indigenous identity and devalue and

objectify their knowledge as superstitious and subjective tokens of a Neolithic

age that merely represent “in situ” museums of a past age of human evolution.

The centrality of

considering self-determination in the formulation of appropriate IP to protect

indigenous knowledge.

If one is truly concerned with protecting

Indigenous Knowledge, a successful resolution of intellectual property rights

for Indigenous Peoples requires a shift of vision in the standard patterns of

legal principals used in interpreting the relationships between Indigenous

Knowledge and Bioprospecting. For the vast majority of Indigenous Peoples

involved in this emerging discussion of TK and IP such a vision begins and ends

with the rights of self-determination manifested in specific political contexts

of struggle. An essential reason for recognising the basic right of self

determination has already been discussed. Focusing on self-determination helps

avoid the objectification process that often impairs the characteristics of

legal regimes designed to ‘help’ them. The history in all countries in this

regard is similar and no less so in Australia. At each historical step in the

‘evolution’ of legal regimes designed to help indigenous peoples, they have inevitably

appeared barbarous and antithetical to ‘modern’ people. Even the legislation

that forcibly removed indigenous children from their families for assimilation

purposes was designed by those who thought they had the best interests of those

children in mind. We should not sit back and confidently judge such epochs as

representative of contexts we have moved beyond. We may have apparently moved

beyond them due to certain types of maturation in community consciousness.

However the methodology of objectification that is still employed will ensure

that future generations will judge current legal regimes designed to help

indigenous people, no matter how laudable the present generation believes them

to be, as equally inappropriate in nature as previous ‘barbaric’ regimes.

Focusing on self-determination and genuine consultation processes discourages

the repetition of such a history.

There are a growing number of western legal

scholars who do acknowledge the centrality of self-determination in such a

discussion. However the inclusion, much less the centrality of such a concept

in standard IP papers focusing on TK is less than common. It is safe to say

that if it is acknowledged it is because of ethical considerations that compel

a considered response to indigenous concerns, rather than representing a

natural emanation of apriori inner orientation among western legal scholars.

The key to transforming the currently relegated status of self-determination in

IP is to convey its importance in standard legal education programs which

facilitates a more natural and sincere consideration by future legal scholars.

One of the hallmarks of ignoring

self-determination is that the typical focus in protecting TK is really upon

protecting the valuable commercial products that result from such knowledge,

rather than upon the unique value of the process of TK itself and the

indigenous communities that represent the foundation of such knowledge. The

first focus is upon economic commodities, the second is upon the relationships

that result in such economic value. On an environmental parallel, it is as if

the discussion is upon protecting the rights of individuals to the resources of

the earth as opposed to protecting the ecological relationships that produce

such resources in the first place. A serious commitment to ecologically

sustainable development requires a shift of vision to the latter, which in the

context of TK and IP requires acknowledging the centrality of

self-determination.

Dealing with the limitations of IP law in

protecting indigenous knowledge: Is a paradigm shift in IP law impending?

Some have commented that it may be impossible to

make a genuine distinction between real and intellectual property in indigenous

customary law (Githaiga 1998, Puri 1995). They are so intimately related that ‘as

the anthropological discussion demonstrates, Aboriginal art is clearly a

'nature or incident' of land ownership: the two in fact are quite inseparable

if not actually the same’ (Gray 1993), they are ‘two sides of the same coin’

(Morphy 1991:49); “knowledge is indistinguishable from land and culture”

(Barsh 1999:40). The interwoven nature of the spiritual, physical and artistic

has also been acknowledged in legal scholarship reflecting on IP and

ethnobiology:

[Spiritual knowledge] is probably the

least protected and explored by the Western legal regimes, although its

significance and interrelatedness with the other two categories [physical and

artistic] is striking.

...the development towards a satisfying protection of

indigenous interests in ethnobiological knowledge heavily builds upon the

outcome of the evaluation of the nature and intrinsic value of ethnobiological

knowledge.

...extensive research on ethnobiological

knowledge will have an important task in the preparatory phase for the adoption

of sui generis legislative protection (Koning 1999).

This interdependence is a reflection of a

spiritual understanding of property in indigenous customary law. Real

‘property’ is a spiritual geography, a ‘sentient landscape’ (Bradley 2001) a

kinship of ancestors, land and creatures that is founded in the ‘Dreaming’

which is

that timeless epoch of creativity that

gave form to the diversity of life, set in motion nature’s cycles, and left its

enduring imprint on the earth’s crust – all species including kindred

humans, were subtly entwined within a transcendent web of meaning that renders

eternally sacred, the process, places, and personages of the natural world.

(Knudtson & Suzuki 1992:39)

Additionally, although there may be indigenous

appreciations of proprietary interests in property, it is fundamentally seen as

a spiritual bequest from the ancestors (Langton 2005). Intellectual property is

therefore primarily a spiritual gift from the spiritual realm and carries with

it obligations of respecting and recognising the ancestors who gave it to us[1].

Taking seriously that IP

has an integrated material and spiritual reality has significant implications

for the jurisprudence of IP law. Thomas Aquinas made the enlightened comment:

'Things known are in the knower according to the mode of the knower.' (Summa

Theologiae, II/II, 1). In other words, the nature of the

object prescribes the method of knowing[2].

This means then that we should be more conscious of IP law as a science that

should be ‘developing

its distinctive modes of inquiry and its essential forms of thought under the

determination of its given subject-matter.’ (Torrance 1969:281) The

relevance for this case is that a reductionist and materialistic framework of

IP law is not a sufficient instrument to perceive or relate to more complex

relational ‘objects’. Materially and spiritually integrated objects require

materially and spiritually integrated methods of knowing to be known. In this

case it is suggested that IP law, and indeed most forms of law, have lagged

behind the other sciences in appreciating that the objects with which it is

concerned are also ‘spiritual’ in the sense of having a more sophisticated

relational nature. (Graham 2003)

On the level of the system of global IP

regulation there are also significant structural limitations. Adam Smith is

credited with contributing the influential ‘invisible hand mechanism’ theory[3]

associated with enlightened self-interest which provides important reasons for

relying on property rights and markets. Basically he suggests that pursuit of

the individual good in markets will benefit the public good. Drahos, however,

suggests that once ‘property rights take the form of privileges in abstract

objects the invisible hand mechanism may cease to be a reliable guide to the

collective good’ (Drahos 1996:139)’ This is partly because of the increasing

ability of powerful factions to manipulate the regulation of IP out of

opportunistic self-interests. So the very system itself is altered to serve

their individual interests. This power increases as the scope and strength of

IP laws increase. Because of the more abstract nature of this property the full

dimensions of this manipulation and cost to society is not yet fully realized.

It is important to again emphasize that property

law is primarily about the rights between people. This is because an important

implication arising is that as there are strengthening of the rights of

exclusion and control, one is arguably allowing one person/company a type of

increased domination and sovereignty over others. This is compellingly argued

by Morris Cohen by illustrating that the dominant feature of property is the

right to exclude others. “But we must not overlook the actual fact that

dominion over things is also imperium over our fellow human beings (Cohen

1927:13).” [4]

In the contemporary Western culture of IP usage

there is arguably a dominance of proprietarianism in which property rights are

given a fundamental and entrenched status over other kinds of rights and

interests (such as various human rights), an assumption of the ‘first

connection thesis’, and a belief in a ‘negative commons’. The first connection

thesis is basically the assumption that the individual who is first able to

economically benefit from a form of property has the right of ownership. The

negative commons idea is the assumption that no one owns the commons of

knowledge and therefore it is open to appropriation by individuals. This is in

alternative to the concept of ‘positive commons’, the idea of knowledge being

owned by everyone. There are other models of the relationship between knowledge

and communities. ‘There are as many kinds of community as there are moral

traditions, shared understandings and ways of life’ (Drahos 1997:185). For

example, it is interesting to note that Imperial China, arguably one of the

most innovative and creative civilizations on earth, arguably did not possess

an intellectual property rights system of any similarity to contemporary

western IP law (Alford 1995). Additionally, similar to types of indigenous

customary law, the imperial Chinese linked their intellectual knowledge and

innovations to an ancient and active relationship with their ancestors. ‘The

Master [Confucius] said: I transmit rather than create; I believe in and love the

Ancients’. (The Analects of Confucius Book VII, Chapter 1). Alford

writes:

Lying at the core of traditional Chinese

society's treatment of intellectual property was the dominant Confucian vision

of the nature of civilization and of the constitutive role played therein by a

shared and still vital past. (Alford 1993:20-21)

While speaking on contemporary China Alford

writes:

The experience of China in recent years

suggests that massive growth is possible without a deep commitment to IP

protection. (Personal correspondence with author June 2006)

Returning to the contemporary western model of

IP law, the proprietary model of rights based focus arguably present a number

of weaknesses. These include but are not limited to various forms of

individualism, anthropocentrism and an instrumentally materialistic rather than

intrinsic or spiritually relational approach of ownership. The capacity for

greed to influence legal development of IP is an extremely significant

deficiency. Drahos commenting on Hegel indicates, “Civil society, once it comes

to realize the pecuniary advantages of intellectual property rights, presses

the state to build ever more elaborate intellectual property systems, systems

which ultimately become a global system” (Drahos 1996:91). This described

process is clearly present in the relationship between the strengthening and

extension of IP through Free Trade Agreements which has been heavily influenced

by the lobbying of political representatives with personal interests and

powerful transnational companies in Washington (Drahos & Braithwaite 2000,

2002). The international instrument which has the greatest influence on

regulating IP relationships is TRIPS, yet an incredibly small group of

influential people devised its creation.

Fewer than 50 individuals had managed to

globalize a set of regulatory norms for the conduct of all those doing business

or aspiring to do business in the information age. (Drahos & Braithewaite

2002: 73)

When combined with increasingly comprehensive

sets of intellectual property rights in regards to abstract objects in a global

system this produces relations of separation, fragmentation of community,

restricts freedom and locks up knowledge previously held as the commons

(Akerlof 2002). In the current framework, the diversity of indigenous customary

legal frameworks are increasingly being rendered powerless to apply the legal

principles they consider important in protecting their own traditional medical

knowledge.

The capacity of all communities to

determine a regulatory structure for the intellectual commons is in the process

of being taken away from them. It is being taken away because the regulation of

abstract objects is progressively shifting from the territorial and the

international to the global. (Drahos 1997: 180)

Additionally, in such a global regulatory

context the current climate of increasing the strength of intellectual property

and the range of subject matter that can be considered property (e.g. recently

expanded to include human genetic information and living organisms) encourages

opportunism in the appropriation of the commons by individuals and corporations

as well as diminishing the remaining sense of the sacredness of life as we

begin the path of even commercializing ourselves.

Another

important criticism of both real and intellectual property is the abstraction,

externalization and alienation of people divorced from the various forms of

property including land and the mental and spiritual creativity of the

individual and community. One aspect of this divorce is seen in the false

dichotomy of the protection of the expression of ideas rather than the ideas

themselves. Only when they are reproduced in a material form in a particular

manner are ideas protected in copyright for example. The individualistic and

dichotomous aspects of intellectual property also diminish the recognition of

creativity as a form of relationship between the individual, community and

inherited common traditions, a concept sometimes referred to as holistic

individualism (Pettit 1996). Marx offers a strong criticism that the ism

of commodities in a framework of capitalistic economics separates intellectual

property from the reality of social relations upon which it is actually based

(Marx 1992). This allows for the peril of ignoring the negative effects of an

overly materialistic/capitalistic system of intellectual property in the social

fragmentation of humanity. This fragmentation largely occurs through the

fostering of extremes of wealth and poverty through the increasing appropriation

of the commons by those in power. This is reflected in a significant pattern of

economic disparities mirrored in the standard feminist and indigenous critiques

of socially unjust objectification of a hierarchy of relationships. These

increasing extremes of wealth and poverty find their greatest contrasts between

developed and developing countries, sometimes generalized as the ‘north-south’

divide enhanced by the location of multinationals in the ‘North’[5].

Even more telling, for the purposes of this chapter, these extremes of wealth

and poverty can be seen between white and black, male and female or more

specifically the dominant Western culture and Indigenous cultures. This does

not necessarily prove that intellectual property law is sexist or racist itself,

although there are those who argue that it is (Warren M. 1992, Mgbeoji 2006).

One can see statements by indigenous peoples that IP represents “a new form of colonization" and "a tactic by the

industrialized countries of the North to confuse and to divert the struggle of

indigenous peoples from their rights to land and resources on, above, and under

it.” (Cited in Posey & Dutfield 1996:211-212) At the very least however

this context of the disparities of wealth and poverty, and the manner in which

IP regulation contributes to this, indicates that the current legal cultural

framework allows for an instrumental use of intellectual property that permits

its use as a tool that can support racist, sexist and nationalist ideologies to

reinforce these disparities of economic injustice from the local to the global

level.

A way forward?

Drahos and others suggest that we must ask what

is the moral theory and set of values associated with intellectual property

usage. IP law should be linked with a strongly articulated conception of public

purpose and role of IP. ‘Legislative experiments with these rights would be

driven by information about their real-world costs and abuses’ (Drahos

1996:224). This reinforces the need for a framework which enables the diversity

of cultural and spiritual traditions a voice in consulting about the set of

values considered appropriate for their local contexts as well enriching the

global framework. This should be combined with empirical economic, social and

scientific measurement mechanisms that confirm projected and actual social

effects of the implementation of such moral theories in IP.

Returning to the paradigm shift:

The majority of social and physical sciences

have to greater or lesser degrees experienced significant paradigm shifts (Kuhn

1965) in previous decades. Although this is a highly complex evolutionary

process, one might make generalizations of the nature of these shifts as moving

from reductionism to holistic diversity. These are conceptual movements towards

recognizing the importance of emergent value in the interface between systems

diversity and interdependent unity. In a recent major scientific work the

summaries of the paradigm shifts in a particular field of science are listed:

Since

the sixties a scientific paradigm shift has been underway towards a Theory of

Evolutionary Systems. During the last two decades an increasing body of

scientific literature on topics of self-organisation has emerged that taken

together represents a huge shift of focus in science:

•

from structures and states to processes and functions

•

from self-correcting to self-organising systems

•

from hierarchical steering to participation

•

from conditions of equilibrium to dynamic balances of non equilibrium

•

from single trajectories to bundles of trajectories

•

from linear causality to circular causality

•

from predictability to relative chance

•

from order and stability to instability, chaos and dynamics

•

from certainty and determination to a larger degree of risk, ambiguity and

uncertainty

•

from reductionism to emergentism

•

from being to becoming

(Arshinov & Fuchs 2003)

Additionally they have commented on how these

shifts also reflect inherently spiritual or increasingly relational ways of

knowing (Polkinghorne 1986). The

ability to perceive a universe that has an integrated spiritual and physical

nature is being enhanced through the process of this paradigm shift. (Laszlo

1989, 2004, 2006)

This chapter suggests there are clear signs of

an impending paradigm shift in intellectual property law as well. The

incredible growth of discussions on the (in)capacity of intellectual property

law to protect indigenous knowledge has resulted in thousands of books and

articles in recent decades being written discussing this context. Many of those

works suggest a need for a ‘sui generis’ or alternate legal

regime to be developed to adequately protect such knowledge. The international

discourse in this area has served to

expose the shortcomings and inadequacies

of existing regimes of intellectual property, contributing to a crisis of

legitimacy in the world intellectual property system. (Coombe 2001)

Rosemary Coombe suggests some of the qualities

of this paradigm shift in accommodating cultural diversity in a united world:

Our challenge, therefore, is to pursue a more

inclusive and culturally pluralist public domain when considering the

privileges to be accorded to intellectual property. Doing so recognizes that

the objectives of sustainable development, the promotion of social cohesion,

and the support for democracy all require respect for the full range

of cultural rights provided by international law. (Coombe 2005)

Some of the corresponding

limitations in IP are reflected in its inability to accommodate the true

sophistication of the dynamics of the interface and synergy between biocultural[6]

diversity and globalization. This represents the greatest challenge to a

largely homogenous IP system that plays a significant destructive role for both

cultural and biological diversity (Mgbeoji 2006). This chapter suggests that

beginning a more conscious engagement with the spiritual dimensions of

indigenous customary law offers powerful catalysts for empowering the paradigm

shift required. Thus IP regulation that involves a focus on consultation

processes with local communities (not just the international representative

level) is considered essential.

Requirement to acknowledge three levels of

value in the protection of indigenous knowledge

Reference is made again to the considerations

related to avoiding the simplification, caricature or objectification of the

nature of indigenous knowledge. The imperative for recognising diversity and

sophistication in indigenous knowledge systems imposes the already mentioned

responsibilities of establishing the primacy of consultative frameworks with

indigenous peoples and the essential recognition of self-determination.

Additionally such consideration imposes the responsibility to adopt flexible

measures of protection capable of responding to the varying values such diverse

and sophisticated knowledge systems represent.

It is suggested that there are three levels of

value that need to be addressed if a long-term solution to IP that adequately

addresses the needs and concerns of indigenous people is to occur. The first

level of value is the instrumental economic value of indigenous “products” that

are appropriated in the bioprospecting process. That is the level at which most

IP discussions take place. The next level is the value of the unique indigenous

knowledge methodologies, metaphysical frameworks and epistemic foundations that

are responsible for the ‘production’ of these commercially valuable products in

the first place. The third level of value is the intrinsic value of the

indigenous people themselves and the web of spiritual, social and ecological

relationships which their identity is intimately associated with.

Due to these differing levels of required

protection, a variety of short, medium and long-term strategies for

transforming IP are necessary to adequately protect TK. Some that have been

suggested are

1. Short term to medium term- e.g. adoption of

Prior Informed Consent frameworks such as WIPO’s formulation of “The

Requirement” (Carvalho 2000), access-restricted indigenous owned databases

(Dutfield 1999), ‘multi-first-nation’ indigenous owned pharmaceutical companies

(Jones 2006).

2. Medium term- e.g. sui generis integration

of human rights (Posey & Dutfield 1996), linguistic human rights

(Skutnabb-Kangas 2000, Maffi 2001), international environmental law and

intellectual property.

3. Long term - ongoing consultation process on

reviving capacity of law to value variety of spiritual consideration of

indigenous peoples based on the development of tools of historical and

metaphysical empowerment. This ultimately translates into a capacity of law to

facilitate indigenous self-determination through being able to involve and

acknowledge the validity of the diversity of intellectual property found in

indigenous customary legal systems.

It is suggested that this last issue of understanding

and protecting spiritual knowledge is the key integrative principle for

understanding many of the problematic IP issues mentioned earlier. It is also

unfortunately, the least discussed and understood issue in the IP debate.

The next section explores the issues associated

with developing the fundamental resource for IP of understanding indigenous

spiritual knowledge in western legal traditions.

Understanding Indigenous Spiritual Knowledge

Traditional knowledge is

diversely represented, but from an Australian Aboriginal perspective there are

some common themes:

1) Spiritual and religious relationships

From a traditional

Aboriginal perspective, traditional knowledge was and is given to the people

from the Dreamtime or spiritual world. Knowledge connects humans and all other

living things through its source. The source of all traditional knowledge is

derived from our spiritual interaction with each other, the Great Creator,

creator beings and the spirits known as the ‘Dreamtime’ (Willis, 1950).

2) Roles and responsibilities

The establishment of

human roles and responsibilities is derived from kinship. Kinship is a

term that relates to the way Aboriginal people traditionally interact with one

another. From a traditional perspective, all living things are related through

the Dreaming and the totem system. People were classed through a totem system

that connected community into extended family relationships. Even people that

were not necessarily related by blood ties could be related through the

traditional kinship system. The expectations and obligations instilled by the

Aboriginal kinship systems still influence contemporary Aboriginal

relationships. It is these relationships that bring together extended families

in communities (Sim, 2003). Traditional kinship

systems were believed to be given to the people through the Dreamtime and

enforced by traditional law. Reciprocal obligations and expectations are

connected to spiritual and religious relationship to spirits, the spirit world,

humans and other living things. Today, roles and reciprocal responsibilities

are being continuously eroded by the imposition of western society,

assimilation and integration. However, those people who are custodians of

traditional knowledge predominately follow the ‘rules’ set out by religious

tradition to pass on and retain traditional knowledge. Breaches of those

‘rules’ degrade and erode the framework in which traditional knowledge is

passed on, resulting in a loss of knowledge to those in the physical world.

Elders are expected to pass on knowledge in the same manner as it was taught,

the role of an ‘elder’ or ‘teacher’ is governed by religious expectations or

‘rules’(Willis 1950).

3) Belonging to knowledge

The establishment and affirmation of a sense of

community is established through kinship and country. Different tribes are

geographically related to different parts of Australia. The understanding of a

specific community will dictate who is included within any specific tribal

group. Knowledge is connected to ‘country’ in a spiritual way. A person’s

connection to ‘country’ and ‘community’, as well as their kinship relationships

through totems, gives them the ability to access, use and pass on traditional

knowledge. Country is understood to be someone’s homeland. A homeland is a place

or area in which a person or group of people have a spiritual connection and a

genealogical history (Bird Rose, 1984). When the people of a community use

traditional knowledge in a culturally accepted manner, they do it for the

benefit of the community and the country. If the community is ‘sick’

(physically or spiritually), the country becomes ‘sick’ (ecologically). If the

country becomes ‘sick’ the people become ‘sick’ (physically or spiritually).

So, there is a special relationship or balance that is kept in check by the

‘good’ use of traditional knowledge and the interaction of spiritual and the

physical forces.

4) Men’s and Women’s Business

The use and understanding of traditional

knowledge is influenced by gender. Knowledge is passed on and used in gender

specific ways that relate equally to the roles of men and women. The division

of knowledge into gender related categories is influenced by religious rules

from the Dreamtime. These formal ‘rules’ or customary laws specifically relate

to how men and woman have the right to access and carry certain knowledge,

visit certain places and participate in ceremonies (Berndt and Berndt,1992).

5) The passage of

knowledge

There are protocols that are derived from the Dreamtime that

influence people in all facets of their lives. The maintenance and passage of

knowledge throughout the community and the forthcoming generations is

influenced by these protocols. The loss and erosion of these protocols hinder

the maintenance of knowledge. These protocols are underpinned by respect for

the natural world, the spiritual world and for human kind as a part of the

‘living’ world (spiritual and physical).

6) Knowledge is animate

From a traditional

Aboriginal worldview there is a notion that knowledge has an animate nature,

due to the characteristic way it is carried and passed on from the spirit world

into the physical realm and back again. ‘What comes from the earth can return

to the earth, what is given can be taken back, what is lost can be found’ (Skuthorpe,

1995).

This last point emphasizes the nature of traditional knowledge being something

that is carried not owned, being a gift given for the benefit of the ‘whole’

community (human and non human) to be used in a very specific way dictated by

the definition of respect forged by the framework established by Aboriginal

religious knowledge (Dreamtime) and spirituality passed on via the spirit

world. If traditional knowledge is not respected it will be returned to the