|

|

Abstract: Overview of the Bahá'ís and Azalis, and mentions of their history in Akka. Includes two excerpts of interest because they refer to "Báb" which in this context refers to a place, not the Prophet. Notes: Author's name is here written as "Harry Charles Lukach," but in other publications the surname is given as "Luke." This book is online in a variety of formats at archive.org, where the image scans below are available in larger zoom. See also a PDF of the entire book with high-resolution images, prepared by Mike Thomas (2022). |

The Fringe of the East:

A journey through past and present provinces of Turkey

by Harry Charles Luke

pages 212, 264-267London: Macmillan and Company, 1913

1. Text

(see images below, and see also a PDF of the complete book [23 MB])

[page 212]... known to Englishmen, and perhaps the most successful, was the Mahdi Mohammed Ahmed of Dongola, under whose tyranny and that of his successor the Sudan was for so long the scene of bloodshed and desolation. Of another, Bahá'u'lláh, and of the remarkable influence exercised by his teachings, something will be said later. The Shiah heresies, however, do not recognize all of the twelve Imams; and their most powerful sect, that of the Isma'iliyeh, breaks away from the orthodox after the death of Ja'far as-Sadiq, the sixth. Ja'far had disinherited his eldest son Isma'il in favour of the next son Musa for being seen in a state of drunkenness; and while the Imamiyeh accepted Musa as seventh Imam, a number of dissidents, mystics, and others, adhered to Isma'il, arguing that his intoxication showed that he attached greater weight to the hidden precepts of Islam than to the observance of its outward formalities!

[page 238]

[The following excerpt including the word Báb refers to a place, not the person.]

... In many parts of Syria and Asia Minor are colonies of Algerians, Cretan Moslems, and Circassians who voluntarily left their countries when they ceased to be governed by Mohammedans. At Bab, for example, where we camped on the first night after leaving Aleppo, we found a number of Circassians; and Manbij, the ancient Bambyke and Hierapolis, where we camped on the following day, is almost wholly a Circassian town.

[page 246]

The following excerpt including the word Báb refers to a place, not the person.]

... It had been our intention to continue eastward to Urfa, and, if possible, to Mardin. Unexpectedly, however, circumstances now arose which made our return to Aleppo imperative. We therefore recrossed the Euphrates a little above Tell Ahmar, and rode north-ward along its right bank, past cliffs honeycombed with caves which once, perhaps, were inhabited, to where it is entered by the river Sajur. For a few miles we rode beside the Sajur, and then returned by Manbij and Bàb to Aleppo.

[page 263]

... Before bringing the tale of this journey to a close, I think it right to pause for a moment at the little port of Acre; for with Acre is connected one of the few

[page 264]

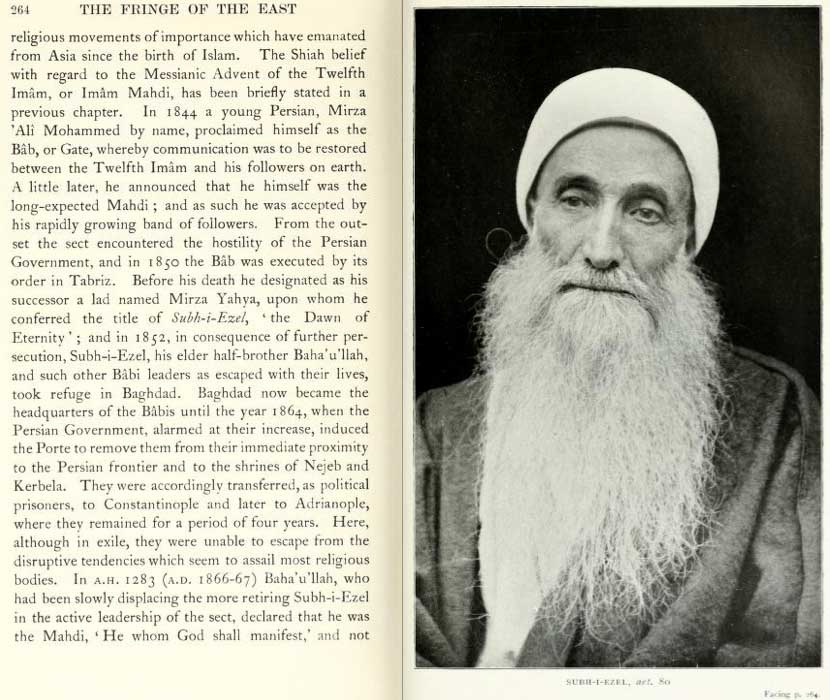

religious movements of importance which have emanated from Asia since the birth of Islam. The Shiah belief with regard to the Messianic Advent of the Twelfth Imam, or Imam Mahdi, has been briefly stated in a previous chapter. In 1844 a young Persian, Mirza 'Ali Mohammed by name, proclaimed himself as the Bab, or Gate, whereby communication was to be restored between the Twelfth Imam and his followers on earth. A little later, he announced that he himself was the long-expected Mahdi; and as such he was accepted by his rapidly growing band of followers. From the outset the sect encountered the hostility of the Persian Government, and in 1850 the Bab was executed by its order in Tabriz. Before his death he designated as his successor a lad named Mirza Yahya, upon whom he conferred the title of Subh-i-Ezel, 'the Dawn of Eternity'; and in 1852, in consequence of further persecution, Subh-i-Ezel [Mirza Yahya, Subh-i-Azal], his elder half-brother Bahá'u'lláh, and such other Babi leaders as escaped with their lives, took refuge in Baghdad. Baghdad now became the headquarters of the Babis until the year 1864, when the Persian Government, alarmed at their increase, induced the Porte to remove them from their immediate proximity to the Persian frontier and to the shrines of Nejeb and Kerbela. They were accordingly transferred, as political prisoners, to Constantinople and later to Adrianople, where they remained for a period of four years. Here, although in exile, they were unable to escape from the disruptive tendencies which seem to assail most religious bodies. In A.H. 1283 (A.D. 1866-67) Bahá'u'lláh, who had been slowly displacing the more retiring Subh-i-Ezel in the active leadership of the sect, declared that he was the Mahdi, 'He whom God shall manifest,' and not

[page 265]

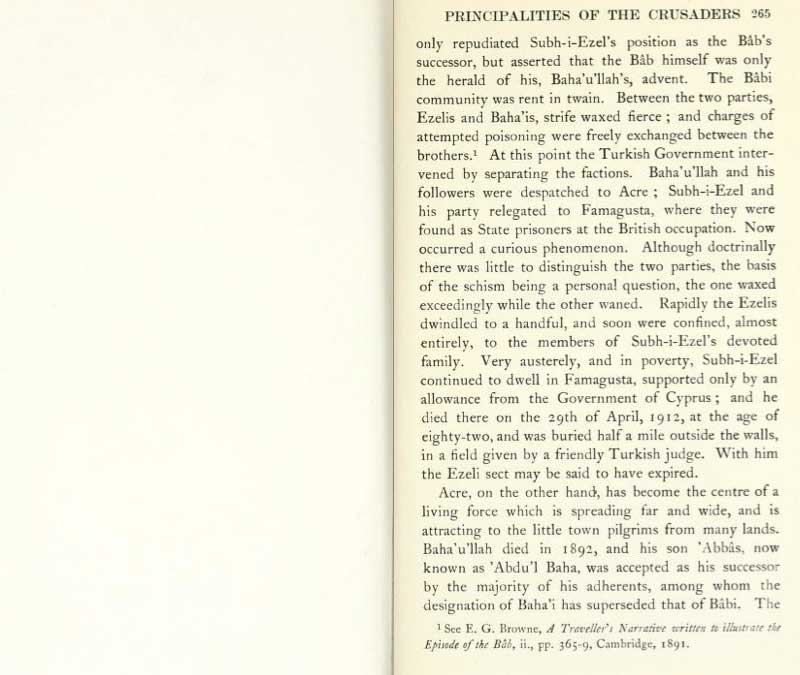

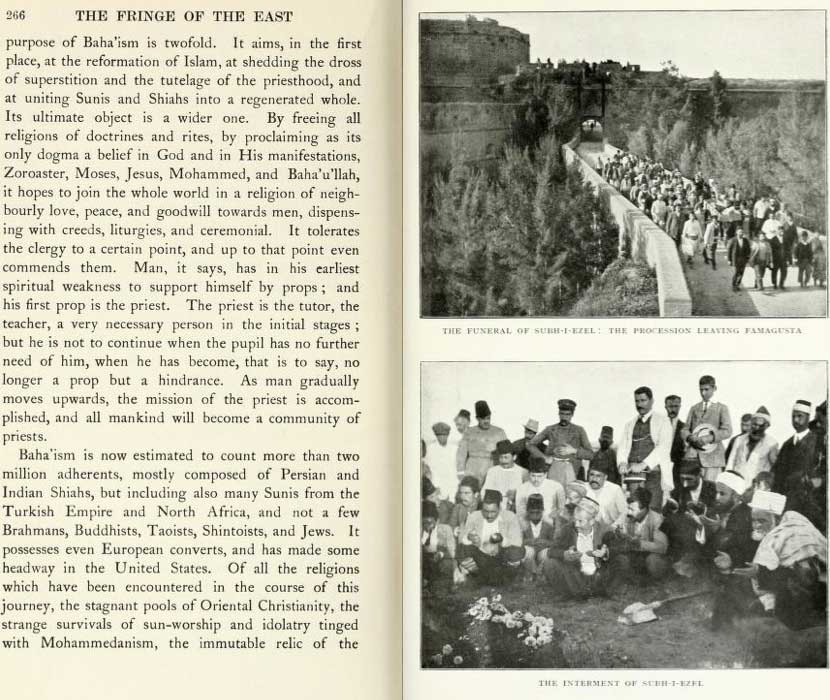

only repudiated Subh-i-Ezel's position as the Bab's successor, but asserted that the Bab himself was only the herald of his, Bahá'u'lláh's, advent. The Babi community was rent in twain. Between the two parties, Ezelis and Bahá'ís, strife waxed fierce; and charges of attempted poisoning were freely exchanged between the brothers.1 At this point the Turkish Government intervened by separating the factions. Bahá'u'lláh and his followers were despatched to Acre; Subh-i-Ezel and his party relegated to Famagusta, where they were found as State prisoners at the British occupation. Now occurred a curious phenomenon. Although doctrinally there was little to distinguish the two parties, the basis of the schism being a personal question, the one waxed exceedingly while the other waned. Rapidly the Ezelis dwindled to a handful, and soon were confined, almost entirely, to the members of Subh-i-Ezel's devoted family. Very austerely, and in poverty, Subh-i-Ezel continued to dwell in Famagusta, supported only by an allowance from the Government of Cyprus; and he died there on the 29th of April, 1912, at the age of eighty-two, and was buried half a mile outside the walls, in a field given by a friendly Turkish judge. With him the Ezeli sect may be said to have expired.

Acre, on the other hand, has become the centre of a living force which is spreading far and wide, and is attracting to the little town pilgrims from many lands. Bahá'u'lláh died in 1892, and his son 'Abbas, now known as 'Abdu'l Baha, was accepted as his successor by the majority of his adherents, among whom the designation of Bahá'í has superseded that of Babi. The

- 1 See E, G. Browne, A Traveller s 'Narrative Written to illustrate the

Episode of the Bab, ii., pp. 365-9, Cambridge, 1891.

[page 266]

purpose of Bahá'ísm is twofold. It aims, in the first place, at the reformation of Islam, at shedding the dross of superstition and the tutelage of the priesthood, and at uniting Sunis and Shiahs into a regenerated whole. Its ultimate object is a wider one. By freeing all religions of doctrines and rites, by proclaiming as its only dogma a belief in God and in His manifestations, Zoroaster, Moses, Jesus, Mohammed, and Bahá'u'lláh, it hopes to join the whole world in a religion of neighbourly love, peace, and goodwill towards men, dispensing with creeds, liturgies, and ceremonial. It tolerates the clergy to a certain point, and up to that point even commends them. Man, it says, has in his earliest spiritual weakness to support himself by props; and his first prop is the priest. The priest is the tutor, the teacher, a very necessary person in the initial stages; but he is not to continue when the pupil has no further need of him, when he has become, that is to say, no longer a prop but a hindrance. As man gradually moves upwards, the mission of the priest is accomplished, and all mankind will become a community of priests.

Bahá'ísm is now estimated to count more than two million adherents, mostly composed of Persian and Indian Shiahs, but including also many Sunis from the Turkish Empire and North Africa, and not a few Brahmans, Buddhists, Taoists, Shintoists, and Jews. It possesses even European converts, and has made some headway in the United States. Of all the religions which have been encountered in the course of this journey, the stagnant pools of Oriental Christianity, the strange survivals of sun-worship and idolatry tinged with Mohammedanism, the immutable relic of the

[page 267]

Samaritans, it is the only one which is alive, which is aggressive, which is extending its frontiers instead of secluding itself within its ancient haunts. It is a thing which may revivify Islam, and make great changes on the face of the Asiatic world. ...

2. Image scans

|

|