|

|

Notes: See excerpt of book at bahai-library.com/shipton_groovin_high_gillespie. Mirrored with permission from www.onecountry.org/e112/e11216as.htm |

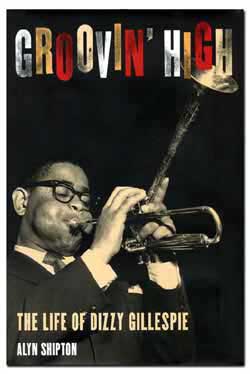

Groovin' High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie, by Alyn Shipton:

Review

by Brad Pokorny

published in One Country, 11:2New York: Bahá'í International Community, 1999-07

Groovin' High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie

Author: Alyn Shipton

Publisher: Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999

Review by: Brad Pokorny

Over the last century and a half, jazz has evolved from the folk songs

of Africans living enslaved in America to a major world musical form,

played and appreciated in nearly every nation on the planet.

One of the major figures in this evolution was John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie,

whose harmonic and rhythmic innovations in the 1940s helped transform

the musical language of jazz into a modernistic expression that captivated

audiences worldwide.

Over the last century and a half, jazz has evolved from the folk songs

of Africans living enslaved in America to a major world musical form,

played and appreciated in nearly every nation on the planet.

One of the major figures in this evolution was John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie,

whose harmonic and rhythmic innovations in the 1940s helped transform

the musical language of jazz into a modernistic expression that captivated

audiences worldwide.

With Groovin' High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie, British jazz reviewer Alyn Shipton has written the first major biography of Mr. Gillespie since his death in 1993. Carefully researched, the book peels back much of the mythology and considerable misinformation that has shrouded important elements of Mr. Gillespie's story - while at the same time reemphasizing and confirming his contributions to the development of jazz and its recognition as a major art form.

Among other things, Mr. Shipton shows that Mr. Gillespie's position in the creation of "bebop" - an original form of jazz that featured fast, complex and asymmetrical melody lines coupled with offbeat rhythms - in many respects outstrips that of saxophonist Charlie Parker, who many jazz historians have previously credited as the major force in that innovation.

Mr. Shipton also outlines Mr. Gillespie's role as the jazz world's ambassador to the world at large. Spreading the message through numerous world-girdling tours, Mr. Gillespie's joyful but hip demeanor, easy-going humor, and style-setting black beret, horn-rimmed spectacles and goatee came to personify the modern jazz musician.

On another level, Groovin' High charts the changes in Mr. Gillespie's personal life, as he transformed from a knife-carrying roughneck in his youth to a genuine world citizen whose support for social causes like racial integration ultimately became synonymous with his identity. That transformation, according to Mr. Shipton, was in part effected by Mr. Gillespie's mid-life conversion to and strong practice of the Bahá'í Faith.

Mr. Shipton writes that after Dizzy became a Bahá'í in the late 1960s, "even though his mean streak would still surface from time to time, those who knew him through the latter part of his life noticed changes. Author Nat Hentoff, for example, wrote: 'I knew Dizzy for some forty years, and he did evolve into a spiritual person. That's a phrase I almost never use, because many of the people who call themselves spiritual would kill for their faith. But Dizzy reached an inner strength and discipline that total pacifists call "soul force." He always had a vivid presence…. He made people feel good, and he was the sound of surprise, even when his horn was in its case.' "

Mr. Gillespie's origins certainly did not presage a life of peace. Born in Cheraw, South Carolina, on 21 October 1917, Mr. Gillespie had a rough childhood. His strict father - a bricklayer and Saturday night musician - often whipped him, and the young Mr. Gillespie was correspondingly pugnacious. "I used to fight anybody, big, small, white or colored," Mr. Gillespie once said. "I was just a devil, a strong devil."

Music was in his blood and he taught himself the trumpet. In the mid-1930s he moved north to Philadelphia and later to New York, where he quickly established himself as a competent young player with a distinctive style. He worked with a number of well-known black bands, including the famed big band of Cab Calloway. Mr. Gillespie's tenure with Mr. Calloway ended when he pulled a knife on the leader and stabbed him in the leg. According to Mr. Shipton, Mr. Calloway had falsely accused Mr. Gillespie of lobbing a spitball at him during a performance - something that was not entirely out of character, inasmuch as Mr. Gillespie was well-known for his high jinks and practical jokes, which was part of the reason for his nickname "Dizzy."

In the 1940s, during late-night jam sessions with Mr. Parker, Mr. Gillespie worked out the new musical ideas that were to become known as bebop and which revolutionized the whole sound of jazz. Mr. Shipton believes that Mr. Gillespie's contributions to bebop have been underestimated.

"By being the one who organized the principal ideas of the beboppers into an intellectual framework, Dizzy was the key figure who allowed the music to progress beyond a small and restricted circle of after-hours enthusiasts," Mr. Shipton writes. "This was a major element in his life, and virtually everyone to whom I spoke stressed Dizzy's exceptional generosity with his time in explaining and exploring musical ideas. Modern jazz might have happened without Dizzy, but it would not have had so clearly articulated a set of harmonic and rhythmic precepts, nor so dramatic a set of recorded examples of these being put into practice."

Throughout the book, Mr. Shipton offers up a careful analysis of Mr. Gillespie's recordings and considerable history and detail about the other musicians who worked with Mr. Gillespie. Inasmuch as Mr. Gillespie played with virtually all of the jazz "greats" of the 1940s through the 1990s, the book thus does double duty as a basic introduction to the history, life-styles and personalities of jazz during its formative years.

As he aged, Mr. Gillespie's contributions to jazz turned more to the social and political realm. In the 1950s, he was sent on a series of world tours by the US State Department, part of a project to showcase American culture. He proved himself an able ambassador, speaking up not only for jazz and America, but for humanity in general.

At an "invitation-only" concert in a swank club in Turkey, Mr. Gillespie noticed a "gang of ragamuffins outside the wall, peering in," writes Mr. Shipton. Before he started playing, Mr. Gillespie asked that the young people be allowed in. "Man, we're here to play for all the people," said Mr. Gillespie.

In the late 1980s, when Mr. Gillespie was in his seventies, he established his "United Nation Orchestra." It featured a roster of musicians from all over the Americas, proving that jazz had truly become an international musical style.

Concludes Mr. Shipton: "By far Dizzy's greatest achievement in his final years was to bury forever the image of the hothead, quick to draw his knife and stand his corner, and to suppress his childhood mean streak once and for all. From the ideal platform of his United Nation Orchestra, with its pathbreaking fusion of musical styles from North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean, he had demonstrated his commitment to the principles of unity, peace, and brotherhood of which he spoke so often. He ended his autobiography with the wish that he would be remembered as a humanitarian. It is the greatest tribute to him to say that his wish came true."

Author: Alyn Shipton

Publisher: Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999

Review by: Brad Pokorny

Over the last century and a half, jazz has evolved from the folk songs

of Africans living enslaved in America to a major world musical form,

played and appreciated in nearly every nation on the planet.

One of the major figures in this evolution was John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie,

whose harmonic and rhythmic innovations in the 1940s helped transform

the musical language of jazz into a modernistic expression that captivated

audiences worldwide.

Over the last century and a half, jazz has evolved from the folk songs

of Africans living enslaved in America to a major world musical form,

played and appreciated in nearly every nation on the planet.

One of the major figures in this evolution was John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie,

whose harmonic and rhythmic innovations in the 1940s helped transform

the musical language of jazz into a modernistic expression that captivated

audiences worldwide.

With Groovin' High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie, British jazz reviewer Alyn Shipton has written the first major biography of Mr. Gillespie since his death in 1993. Carefully researched, the book peels back much of the mythology and considerable misinformation that has shrouded important elements of Mr. Gillespie's story - while at the same time reemphasizing and confirming his contributions to the development of jazz and its recognition as a major art form.

Among other things, Mr. Shipton shows that Mr. Gillespie's position in the creation of "bebop" - an original form of jazz that featured fast, complex and asymmetrical melody lines coupled with offbeat rhythms - in many respects outstrips that of saxophonist Charlie Parker, who many jazz historians have previously credited as the major force in that innovation.

Mr. Shipton also outlines Mr. Gillespie's role as the jazz world's ambassador to the world at large. Spreading the message through numerous world-girdling tours, Mr. Gillespie's joyful but hip demeanor, easy-going humor, and style-setting black beret, horn-rimmed spectacles and goatee came to personify the modern jazz musician.

On another level, Groovin' High charts the changes in Mr. Gillespie's personal life, as he transformed from a knife-carrying roughneck in his youth to a genuine world citizen whose support for social causes like racial integration ultimately became synonymous with his identity. That transformation, according to Mr. Shipton, was in part effected by Mr. Gillespie's mid-life conversion to and strong practice of the Bahá'í Faith.

Mr. Shipton writes that after Dizzy became a Bahá'í in the late 1960s, "even though his mean streak would still surface from time to time, those who knew him through the latter part of his life noticed changes. Author Nat Hentoff, for example, wrote: 'I knew Dizzy for some forty years, and he did evolve into a spiritual person. That's a phrase I almost never use, because many of the people who call themselves spiritual would kill for their faith. But Dizzy reached an inner strength and discipline that total pacifists call "soul force." He always had a vivid presence…. He made people feel good, and he was the sound of surprise, even when his horn was in its case.' "

Mr. Gillespie's origins certainly did not presage a life of peace. Born in Cheraw, South Carolina, on 21 October 1917, Mr. Gillespie had a rough childhood. His strict father - a bricklayer and Saturday night musician - often whipped him, and the young Mr. Gillespie was correspondingly pugnacious. "I used to fight anybody, big, small, white or colored," Mr. Gillespie once said. "I was just a devil, a strong devil."

Music was in his blood and he taught himself the trumpet. In the mid-1930s he moved north to Philadelphia and later to New York, where he quickly established himself as a competent young player with a distinctive style. He worked with a number of well-known black bands, including the famed big band of Cab Calloway. Mr. Gillespie's tenure with Mr. Calloway ended when he pulled a knife on the leader and stabbed him in the leg. According to Mr. Shipton, Mr. Calloway had falsely accused Mr. Gillespie of lobbing a spitball at him during a performance - something that was not entirely out of character, inasmuch as Mr. Gillespie was well-known for his high jinks and practical jokes, which was part of the reason for his nickname "Dizzy."

In the 1940s, during late-night jam sessions with Mr. Parker, Mr. Gillespie worked out the new musical ideas that were to become known as bebop and which revolutionized the whole sound of jazz. Mr. Shipton believes that Mr. Gillespie's contributions to bebop have been underestimated.

"By being the one who organized the principal ideas of the beboppers into an intellectual framework, Dizzy was the key figure who allowed the music to progress beyond a small and restricted circle of after-hours enthusiasts," Mr. Shipton writes. "This was a major element in his life, and virtually everyone to whom I spoke stressed Dizzy's exceptional generosity with his time in explaining and exploring musical ideas. Modern jazz might have happened without Dizzy, but it would not have had so clearly articulated a set of harmonic and rhythmic precepts, nor so dramatic a set of recorded examples of these being put into practice."

Throughout the book, Mr. Shipton offers up a careful analysis of Mr. Gillespie's recordings and considerable history and detail about the other musicians who worked with Mr. Gillespie. Inasmuch as Mr. Gillespie played with virtually all of the jazz "greats" of the 1940s through the 1990s, the book thus does double duty as a basic introduction to the history, life-styles and personalities of jazz during its formative years.

As he aged, Mr. Gillespie's contributions to jazz turned more to the social and political realm. In the 1950s, he was sent on a series of world tours by the US State Department, part of a project to showcase American culture. He proved himself an able ambassador, speaking up not only for jazz and America, but for humanity in general.

At an "invitation-only" concert in a swank club in Turkey, Mr. Gillespie noticed a "gang of ragamuffins outside the wall, peering in," writes Mr. Shipton. Before he started playing, Mr. Gillespie asked that the young people be allowed in. "Man, we're here to play for all the people," said Mr. Gillespie.

In the late 1980s, when Mr. Gillespie was in his seventies, he established his "United Nation Orchestra." It featured a roster of musicians from all over the Americas, proving that jazz had truly become an international musical style.

Concludes Mr. Shipton: "By far Dizzy's greatest achievement in his final years was to bury forever the image of the hothead, quick to draw his knife and stand his corner, and to suppress his childhood mean streak once and for all. From the ideal platform of his United Nation Orchestra, with its pathbreaking fusion of musical styles from North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean, he had demonstrated his commitment to the principles of unity, peace, and brotherhood of which he spoke so often. He ended his autobiography with the wish that he would be remembered as a humanitarian. It is the greatest tribute to him to say that his wish came true."

|

|