|

Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia:

With Notes on Russia, Koords, Toorkomans, Nestorians, Khiva, and Persia

by Lady Mary (Leonora Woulfe) Sheil

|

chapter 13 | start page | single page | chapter 15 |  |

Chapter 14

Toorkoman hostages – The banks of the Goorgan – Toorkoman horses – Easter – Chaldæan bishop – Mistaken ideas of seclusion among Persian women – Dosing of Persian doctors – Ashoorada – Successful foray of Toorkomans against the Russians – Journey to Ispahan – Dreadful heat – Kouderood – Persian beggar – The unlawful lamb – Persian pigs.

February. – Among the curiosities of Tehran, to me at least, were the Toorkoman women whose husbands were living in the town as hostages from the tribe of Goklan. This branch of Toorkomans resides in the vicinity of Asterabad, in the south-east angle of the Caspian. Unlike the other Toorkomans who roam in freedom between the Caspian and the Oxus, the Goklans are, from the above circumstance of their close vicinity to Persia, more or less subject to the Shah. They are, on this account, compelled to furnish hostages, to the number of forty or fifty families; but this does not prevent them from carrying their foraging excursions into Persia whenever commotion in the latter country affords a likelihood of impunity. Did we not know the Toorkomans to be one of the most detestable races among mankind, we should be disposed to commiserate their transfer from the beautiful scenery near the banks of the Goorgan, and the freedom of their alaïchigs, or felt and wicker tents, to the shocking atmosphere of their habitations in Tehran, where they are never allowed to pass the gates. However, there are periodical

Page 208

reliefs, which enable them to return to their obas or encampments. Men and women are extremely disagreeable in appearance, and the women particularly so. Their faces are flat and broad, with high cheek-bones, the nose short, wide, and flat, the eyes small, deep-set, and jet-black, the complexion a tawny yellow. As they belong to the genuine Turkish race, one is astonished in comparing them with the well-looking Osmanlis of Constantinople, whose forefathers no doubt resembled these marauders. But a little reflection soon explains the change. Intermarriage with Georgians and Circassians, Koords, Arabs, Albanians, Sclavonians, Greeks, and Armenians, has no doubt modified the frightful Mongolian features of the genuine Turk. These Toorkoman women wander through the streets with the utmost unconcern, wholly unveiled. Their dress is equally remarkable and unbecoming; it consists of red narrow trousers, and a coarse red cloth coat or vest reaching below the knee, surmounted with yellow handkerchiefs on the head and neck. The character of the Toorkomans admits of as little praise as their persons. That they should be avaricious, greedy of plunder, and ferocious, is the natural result of their mode of life. But they are also reputed to be full of treachery, and ready to sell their guest at the moment of showing him hospitality in their tents. These vicious traits are not relieved by courage. A Toorkoman is a marauder, and nothing more; always ready to pillage, and always avoiding fighting as much as possible. They do, however, sometimes make a headlong charge. One of their chiefs said that on such occasions they couch their lances, bend their heads below the horse's

Page 209

neck, shut their eyes, and then – Ya Allāh! forward! These ādamferoosh, men-sellers, are the bane and the bliss of Persian pilgrims to Meshed. On the one hand, they seize and carry them off for sale in Khiva and Bokhara; on the other, they help them to Paradise by the merit of the dangers encountered in visiting the shrine of Imām Reza at Meshed. Can anything more dreadful be conceived than a body of these ferocious Toorkomans dashing down at the dawn of day on a helpless village, or still more helpless caravan of pilgrims, – men, women, and children? The old and feeble are killed, the others are bound, and hastily carried off to the desert. They call themselves Soonnee Mahommedans, and on that pretext make it lawful to carry off Persian Sheeahs. Should any of their captives happen to be Soonnees, like men of conscience, unwilling to break the law, the Toorkomans beat them until they proclaim themselves Sheeahs. The goodness of their horses enables them to make forays of immense length. Formerly, when Persia was disturbed and divided, they used to make chepāwuls, or forays, of several hundred miles; but in these days they do not venture on such distant excursions, where retreat might be difficult. It is said that, after being trained, these horses can travel a hundred miles a-day for several consecutive days. Their pace is described to be a long straddling walk, approaching to a trot, which they maintain almost day and night. The rider's powers of bearing fatigue must be not far short of those of the animal. Captives in good circumstances can always ransom themselves. The sister of a gentleman of Afghanistan, a pensioner of the British Government, coming from Meshed

Page 210

with her family, was carried off by the Yamoot Toorkomans, midway between that city and Tehran. Her release cost 500 tomans, about 250l. Had she not been ransomed she would certainly have been sold in Khiva. I have frequently seen at the gate of the Mission very poor-looking men with long chains suspended from their necks. This was a signal that sons or daughters had been carried off by the Toorkomans, whose release they were endeavouring to purchase by collecting alms. The Goklans are a comparatively small tribe, of about ten thousand tents or families, and live surrounded by enemies. On the north are the Yamoot Toorkomans, dwelling on the rivers Atrek and Goorgan; on the east are the Tekkeh Toorkomans; and on the south is Persia. The two former tribes are very powerful, and both wage constant feuds with the Goklans; but the Toorkomans never sell one another. The Goklans are, however, a compact, united tribe, dwelling in a strong country, and maintain their ground well. These marauders sometimes carry their boldness to such a length as to seize people close to the ramparts of Asterabad – nay, even occasionally within the walls – and carry them off to the desert.

March. – Nowrooz and the other festivals passed exactly as the year before, and were therefore deprived of any interest, from the absence of novelty. Our own religious festival of Easter was approaching, and it was time to think of that solemnity. One of the inconveniences of Tehran to a Catholic family was the want of a clergyman of that church, whom we consequently were obliged to send for from a distance. On one occasion, a French gentleman of the order of Lazarists had travelled

Page 211

five hundred miles to Tehran at our earnest desire, and after some time returned the same long journey to Salmas, in Azerbijan. At another time, a Catholic Armenian clergyman, who had been educated at Rome, came from Ispahan to oblige us; and on a third occasion we were indebted to a bishop of the Chaldean Catholics in Azerbijan, who came from Tabreez, four hundred miles, to render us spiritual assistance. The bishop was a man of strikingly imposing and dignified appearance; he had formerly been Patriarch to the Chaldean Catholics in Moosul, from which place he had been transferred to Azerbijan. He too had been educated in Rome, and spoke Italian perfectly. To us, who had been always accustomed to bear Mass said in the Latin language, it was strange to listen to the service in old Armenian, which not even the Armenian congregation who attended at our chapel understood, and in ancient Kaldanee, or Chaldæan. It will surprise some English people to hear that Latin is not the universal language of Roman Catholics in their religious ceremonies; but any one who on Twelfth Day has been in the Church of the Propaganda in Rome will have seen Mass celebrated in Coptic, ancient Greek, Syriac, Armenian, Chaldaic, and other old tongues, which, like Latin, have now ceased to be the colloquial language of the people. This Chaldean Bishop did not seem to be filled with charitable sentiments towards his brethren of the Nestorian faith, particularly towards the clergy of that community. Being himself a man of education, he was at no loss for opportunities of ridiculing their ignorance, forgetful of their seclusion in the mountains of Koordistan, and of what he himself would have

Page 212

been had not his good fortune sent him to Rome. In worldly wealth this successor of the Apostles was very primitive; one of his flock acted both as servant and clerk, and a small remuneration was a sufficient inducement for undertaking the long and fatiguing journey from Tabreez to Tehran. His revenue was entirely derived from the voluntary contributions of his flock; and even this scanty source of subsistence had recently, owing to some disagreements, ceased. The "voluntary system" is certainly not a thriving one in the East, whether for Armenians or Chaldæans, Catholic or otherwise. I have never seen a clergyman of these communities who did not seem to be in extreme poverty excepting at Tabreez, where the presence of wealthy Armenian merchants secures for their priesthood a comfortable subsistence. There are very few Catholics in Tehran, and the greater part of these were Europeans. Our congregation seldom exceeded from ten to fifteen people. (Note E.)

April. – My residence here has thoroughly dissipated my English ideas of the seclusion and servitude in which Persian women are supposed to live. Bondage, to a certain extent, there may be, but seclusion has no existence. Daily experience strengthens an opinion I had formed of the extent of the freedom in which they spend their lives, particularly whenever I pass the door of the physician to the Mission. Jealousy, at all events, does not seem to disturb Persian life in the anderoon, or to form a part of the character of Persians. The doctor's door and house are crowded with women, of all ages and of all ranks, from princesses downwards, who come to him to recount their ailments. It seems their applications for

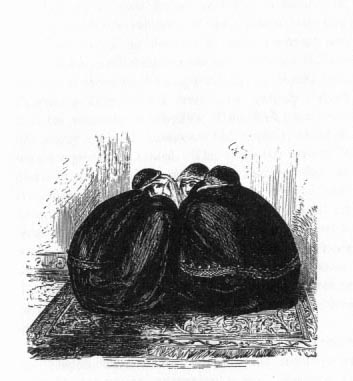

Facing Page 213

Persian Women seated on a carpet gossiping outside the Doctor's door. Page 213.

Page 213

succour are often founded on most frivolous motives; gossip rather than physic being frequently their object. Sometimes, on the other hand, they seem to think all the diseases of Pandora's box are concentrated in their persons, when in reality they are perfectly well, but still insist on being "treated." A princess in the streets of Tehran is as little distinguishable as a peasant, which enables her to consult her medical adviser without any recognition of her rank. The dreadful practice of the Persian doctors is quite enough to drive the fair dames of Tehran to an English physician. I am told they give the most nauseating draughts, in immense quantities, to their patients two or three quarts at a time. Then they divide all maladies into cold and hot, which are to be attacked by corresponding opposite medicines. Thus a hot disease is to be combated by a cold remedy. The classifications of these last are somewhat fanciful. Pepper, I know, is cold, and ice, I think, is "hot." It can hardly be otherwise than hot, for it is applied to the stomach in large pieces during cholera. It must be admitted, in extenuation of the freedom allowed to themselves by Persian ladies in their medical visits, that a physician is a privileged person in Persia. The anderoon seems open to him. Husbands and brothers, in company with their wives and sisters, used to sit in their anderoon with our "hakeem sahib," gossiping and chatting as gaily and freely as they would do in Europe. It is a pity that these cheerful Iranees are so far off; they would otherwise soon become Feringhees. With all their alacrity to endure a life of roughness, or even hardship, they have a vast aptitude for luxury and enjoyment; which may be

Page 214

regarded as the high road to civilization. Their wants are increasing daily, and these wants must be supplied from Europe.

May 1st. – To the great dismay of all the courtiers the Shah has resolved to undertake a journey to Ispahan. The unpopularity of the movement is general and reasonable. The courtiers are expected to accompany his Majesty without receiving any compensation for the heavy expense they must inevitably undergo. The camp of a king of Persia on a journey resembles that of a large army. There are cavalry, infantry, artillery, bazars, and camp-followers innumerable. Each of the courtiers has a large retinue of servants, mules, led-horses, tents, &c.; and he lays in a store of tea, sugar, tobacco, spices, and other edibles, as if he were undertaking a voyage of discovery in some unknown region. This arises from the nomadic habits so prevalent throughout the nation. A tent feels to them like a house and a home; and in a sauntering journey, like that of the Shah of Persia, they love to travel luxuriously.

We, too, prepared with regret to swell the pomp of the royal camp. The daily increasing heat, and other circumstances, made me heartily desire to remain in Tehran; but the Russian Mission having resolved to accompany the Shah, the English Mission could not show his Majesty less respect; and I thought it preferable to brave all the discomfort of the journey rather than remain in the solitude of Tehran.

The Shah, intending to reach his destination by a circuitous route, had already taken his departure from Tehran, when intelligence arrived from Asterabad which

Page 215

excited alarm, amazement, and ridicule. In the island of Ashoorada, at the south-east angle of the Caspian, the Russians have a naval establishment for their ships-of-war, when cruising in the above portion of that sea. They seldom have at this station less than two or three vessels of their military navy, whose occupation is ostensibly confined to the coercion of the neighbouring Toorkomans. This coercion, it may be presumed, is exercised with no light hand over these marauders. These Toorkoman Vikingrs [sic] belong to the tribe of Yemoot, and, by means of their boats, commit depredations on the Persian coast, carrying off men, women, and children, with every other description of booty. Not being permitted to maintain a navy on their own sea, the helpless Persians are forced to have recourse to Russia for protection. The Toorkomans, smarting under a control so foreign to their habits, and annoyed by the deprivation of their usual pillaging excursions, determined to have revenge. It was a bold thing of these half-armed barbarians to think even of contending in their open boats with the steamers and soldiers of Russia; nevertheless they ventured, and in the execution of their plan they showed a keen appreciation of the character and habits of the Russians. On Easter eve, or Easter night, when every Muscovite is supposed to be engaged in libations of thanksgiving for release from his rigorous fast, they landed in a creek of the small island, and immediately made their onslaught on the Russians living on shore. No resistance was made – perhaps the advanced stage to which their festivities had been carried admitted of none – so, at least, it was currently said at Tehran. Some Russians were killed and

Page 216

wounded, and ten or fifteen persons, men and women, were carried into slavery by the Toorkomans, who returned without delay to the mainland. But the amazing and amusing part of the affair was the conduct of the war-steamer lying in the harbour. Not the least attempt was made to succour the beleaguered party on shore. She got up her steam and rushed about the harbour, firing her guns at everything and nothing. The Persians said that she, too, was evidently as drunk as the crew. This humiliating blow from a few half-armed barbarians has made the Russian Mission look very grave, dignified, and menacing. The occurrence is alarming, too; for no one thinks it will remain long without a sequel, as these Yemoot Toorkomans are nominally Persian subjects, or at least claimed as such. In their lively, bantering manner, the Persians protest that the whole transaction – attack, slaughter, and capture – was got up and instigated by the Russians themselves, as a prelude to further encroachments. But we must commence our journey to Ispahan, and leave Prince — to decide the matter with his "auguste maître."

Kouderood, May 21st. – We quitted Tehran on the 11th, and have got over only half our most fatiguing journey. On leaving the city the thermometer was at the very endurable temperature of 75°; but the moment we entered the tents it rose to 95°, and daily increased. This sudden change was overwhelming. I never suffered so much; and every one seemed equally depressed. Our mode of travelling, too, augmented greatly the discomfort and fatigue, but was absolutely necessary with reference to the servants and horses. We started every morning at

Page 217

three o'clock, and halted at about seven or eight, when the sun was overpowering, then recommenced our journey at about four o'clock in the afternoon. It was impossible to sleep during the great heat of the day; and often the nights were so hot that the only moment one could repose was the cool hour when we were forced to rise.

The person most to be pitied, however, was our unfortunate French cook. After mounting his horse at three in the morning, and reaching the tents at seven or eight, he began his operations for breakfast. Whether he ever rested at all I do not know; but the first object I used to see on arriving at our encampment for the night was poor Dunkel, cooking dinner in the open air, with a few unburnt bricks for a kitchen-range. It certainly was "désolant," as he himself used to say. An Englishman would have gone distracted under such circumstances; but the Frenchman was a philosopher.

Our road lay through the district of Savah, by a constant but imperceptible descent. The city of Savah is situated in a burning plain where the soil is impregnated with salt, and, like nearly everything in Persia, is in complete decay. We were now advancing into the centre of the great province of Irak. No part of Persia seems to be without clans and septs; for here, too, and in the adjoining districts, several Toork tribes are resident. A wonderful race of conquerors were certainly the Turks. Half the world at one time or another seems to have fallen under their dominion; and not only did they achieve, but, more difficult still, they often contrived to preserve their conquests. Good sense and courage seem to have been

Page 218

the special qualities of the race. Even at this day it is possible to distinguish between the Toork and Lek, or genuine Persian tribes, by the countenance. The former is almost invariably marked by gravity, and often by uncouthness. The Lek is wild, and frequently ferocious in countenance. He has a keen and hungry look about him that reminds one of a tiger-cat.

The heat at last became so excessive, and I and others felt so exhausted in consequence, that we took refuge in this village, or rather encamped near it, to recruit our strength in its more elevated position. This is the great advantage possessed by Persia over other hot countries. In few places is it out of one's power to ascend from a hot, burning plain to a delightful yeilāk, where one is revived by comparatively cool breezes. We have now been here nearly a week, and are, I am sorry to say, to leave it in a day or two. Our tents are pitched close to a clear stream, near a grove of olives, and there are a few large trees overshadowing us. On a hill near us are the ruins of some old castle, which looks very picturesque. The ground is covered with wild flowers and aromatic herbs; and our olive grove is filled with nightingales. Frances and Crab spend their day paddling in the stream; and, altogether, I feel sure any change we make will be for the worse.

Sultanabad, May 25th. – We have left pleasant Kouderood, and have again descended to the same scorching atmosphere as before. This town is placed as usual in a plain bounded by hills; but in this instance the plain was fertile, covered with cornfields nearly ready for the sickle. The town looks more thriving than customary,

Page 219

owing, perhaps, to its containing several manufactories, or rather looms, for making silk.

I was a good deal struck by the conduct of a beggar, very old and decrepit, who approached our camp, loudly demanding charity. I sent him some pence, which he sent back with an indignant message, that "Pool e seeāh nemee-geerem" (I am not in the habit of accepting black (copper) money). This was the more curious, as a silk-weaver, passing by the tents, in answer to our inquiry, said that his wages were threepence a-day. This sum appears surprisingly small, particularly as almost every Persian is married; but the price of food is on a corresponding scale. I question if the extreme cheapness of Persia be owing to a great redundancy of food, and suspect it may rather be attributable to a scarcity of money. Still food is abundant: bread is generally twopence for 6 1/2 lbs.; mutton a shilling for 6 1/2 lbs.; beef fivepence for 6 1/2 lbs.; but such beef, invariably an old cow, fit for nothing but to die! This brings to my mind a circumstance which gives an idea of the kind of animal considered fit for food by Persians. Our butler, Mahommed Agha, came to me in great haste, and said, with much solemnity, "Khanum, your fattest lamb wants to make himself unlawful, therefore I propose to kill him at once." It appeared the poor lamb was very ill, and about to die, and that to make him lawful food his throat should be cut. Persian phraseology is sometimes curious. One day Agha Hassan, our head groom, came to me and said that my horse had become my sacrifice. He had been ill, and this was his mode of announcing the catastrophe of his death; the meaning being that my misfortunes had descended

Page 220

on the head of my poor steed. The groom had kept a pig in the stable with the horse, for the purpose of rendering the same service to the latter, but he could not avert fate. This is a common practice in Persia; and it is interesting to watch the friendship which springs up between the pig and the horse.

These domesticated wild pigs are peculiar in their attachments. There was an English consul at Samsoon who kept one of these animals, which used to accompany him out shooting, and, I believe, did all the duty of a pointer. He was miserable apart from his master. Whenever the latter paid a visit to the Pasha or the Cazee, he naturally declined to allow his pig to accompany him. The pig, however, was certain to ferret him out, and present himself, equally regardless of the feelings of the true believers and of the confusion of the Consul. These inconvenient demonstrations of affection cost the poor pig his life. The ungrateful Consul put him to death. Before finishing with pigs, I must mention another anecdote relative to their wonderful power of scent. A member of the Mission was once chased two or three miles openmouthed by an immense half-starved pig over hedges and ditches, walls and canals, and barely escaped with his life. He had a piece of ham in his pocket, which the pig's potent olfactories had discovered. Every one knows that the flesh of this animal is forbidden to Mahommedans, and that, in general, it even excites their disgust. Yet they sometimes overcome their antipathy. An English gentleman happening to receive a present of a wild boar, a prince of the blood royal insisted on dining with him, with the proviso that the dinner was to consist solely of

Page 221

pig. Accordingly pig in all possible shapes appeared at table. There was roast pig and boiled pig, fried pig and grilled pig, and pig's head and pig's feet, of each of which his royal highness and one of his brothers freely partook.8

These dissertations upon pigs have drawn us away from the fertile plain of Sultānabād. With all its salt and sand a large portion of the soil of Persia is clayey and good, and requires water only and population to fertilise the plains. The want of good government has dispersed the population; the want of population has dissipated the water, that is, ruined the kanāts; and the want of water has converted three-fourths of the country into barrenness. I begin to conceive that ancient Persia may have been peopled in a high degree.

8 There is no reason for concealing that the giver of this eccentric feast was the former most excellent physician of the Mission, Dr. Charles Bell. Few men have enjoyed so distinguished a reputation for medical knowledge in Persia as this gentleman, to which his abilities well entitled him. – J. S.

Page 222

|

chapter 13 | start page | single page | chapter 15 |  |

|

|