|

|

Abstract: The American Bahá’í community’s historical efforts to address racial injustice which has afflicted the United States since its founding. Notes: Mirrored from bahaiworld.bahai.org (part of the collection History). |

The Bahá'í Response to Racial Injustice and Pursuit of Racial Unity:

Part 1 (1912-1996)

by Richard Thomas

published in Bahá'í World2021-01

This is the first of two articles focusing on the American Bahá'í community's efforts to bring about racial unity. This first article is a historical survey of nine decades of earnest striving and struggle in the cause of justice. A second article, to be published in the future, will focus on the profound developments in the Bahá'í world over the past twenty-five years, beginning with 1996, and explore their implications for addressing racial injustice today and in the years to come.

| Contemporary images of the above, by Rebecca Passa, July 2020 [not part of original article]: | |||

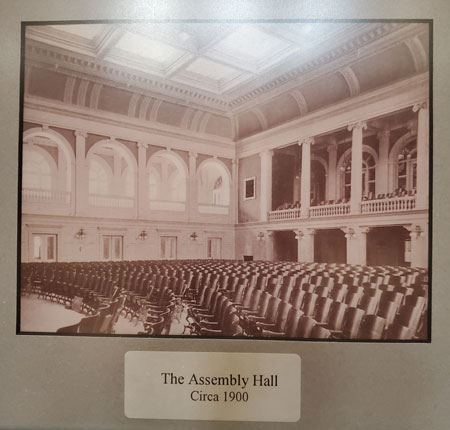

click for larger image Photograph on the wall of the building. |

click for larger image Contemporary improvements of the building. |

click for larger image Contemporary improvements of the building. |

|

| |||

During some of America's worst racial crises, the Bahá'í community has joined the gallant struggle not only to hold back the tide of racism but also to build a multiracial community based on the recognition of the organic unity of the human race. Inspired by this spiritual and moral principle, the Bahá'í community, though relatively small in number and resources, has, for well over a century, sought ways to contribute to the nation's efforts to achieve racial justice and racial unity. This has been a work in progress, humbly shared with others. It is an ongoing endeavor, one the Bahá'í community recognizes as "a long and thorny path beset with pitfalls." (3. Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice.)

As the Bahá'í community learns how best to build and sustain a multiracial community committed to racial justice and racial unity, it aspires to contribute to the broader struggle in society and to learn from the insights being generated by thoughtful individuals and groups working for a more just and united society.

This article provides a historical perspective on the Bahá'í community's contribution to racial unity in the United States between 1912 and 1996. The period of 1996 to the present—a "turning point" that the Universal House of Justice characterized as setting "the Bahá'í world on a new course" (4. Universal House of Justice, from a letter dated 10 April 2011 in Extracts from Letters Written on Behalf of the Universal House of Justice to Individual Believers in the United States on the Topic of Achieving Racial Unity (Updated Compilation 1996-2020), [7],5. Available at greenlakebahaischool.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/compilation-uhj-on-race-unity-1996-2020.pdf. One aim of this extraordinary period from 1996 to the present has been to empower distinct populations and, indeed, the masses of humanity to take ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and social development. A future article will look at the impact of this latter period on the approach to the racial crisis in the United States. Recent articles on community building and approaches to building racial unity in smaller geographic spaces provide valuable insights about developments during this period.) and increasing its capacity to contribute to social progress—is still underway. During the past twenty-five years, the Bahá'í community's capacity to contribute to humanity's efforts to overcome deep-rooted social and spiritual ills has advanced significantly, and a subsequent article will focus on the implications of this distinctive period on the community's ability to foster racial justice and unity.

'Abdu'l-Bahá's Visit: Laying the Foundation for Racial Unity, 1912-1921

The Bahá'í community's first major contribution to racial unity began in 1912 when 'Abdul'-Bahá, the son of the Founder of the Bahá'í Faith, Bahá'u'lláh (1817-1892), visited the United States. His historic visit occurred during one of the worst periods of racial terrorism in the United States against African Americans. According to historians John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, "In the first year of the new century more than 100 Negroes were lynched and before the outbreak of World War 1 the number for the century was 1, 100." (5. Franklin and Moss, 282.) In 1906, riots broke out in Atlanta, Georgia, where "whites began to attack every Negro they saw." (6. ibid.) That same year, race riots also occurred in Brownsville, Texas. (7. ibid.) Two years later, in 1908, there were race riots in Springfield, Illinois. (8. ibid.) And in 1910, nation-wide race riots erupted in the wake of the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson (Black) and Jim Jeffries (White) in Reno, Nevada, in July of that year. (9. Matt Reimann, "When a black fighter won 'the fight of the century,' race riots erupted across America." May 25, 2017.)

Racial turmoil prevailed before and after 'Abdu'l-Bahá's visit. Yet, in this raging period of racial terrorism and conflict, He proclaimed a spiritual message of racial unity and love, and infused this message into the heart and soul of the fledgling Bahá'í community—a community still struggling to discover its role in promoting racial amity. Before His visit to the United States, 'Abdu'l-Bahá sent a message to the 1911 Universal Race Conference in London in which He compared humankind to a flower garden adorned with different colors and shapes that "enhance the loveliness of each other." (10. G. Spiller, ed., Papers on Inter-Racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress Held at the University of London, July 26-29, 1911. Rev. ed. (Citadel Press, 1970), 208.)

The next year, in April, 1912, He gave a talk at Howard University, the premier African-American university in Washington D.C. A companion who kept diaries of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's Western tours and lectures wrote that whenever 'Abdu'l-Bahá witnessed racial diversity, He was compelled to call attention to it. For example, His companion reported that, during His talk at Howard University, "here, as elsewhere, when both white and colored people were present, 'Abdu'l-Bahá seemed happiest." Looking over the racially mixed audience, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had remarked: "Today I am most happy, for I see a gathering of the servants of God. I see white and black sitting together." (11. 'Abdu'l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/098175321)

After two talks the next day, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was visibly tired as He prepared for the third talk. He was not planning to talk long; but, here again, when he saw Blacks and Whites in the audience, He became inspired. "A meeting such as this seems like a beautiful cluster of precious jewels—pearls, rubies, diamonds, sapphires. It is a source of joy and delight. Whatever is conducive to the unity of the world of mankind is most acceptable and praiseworthy." (12. ibid.) 'Abdu'l-Bahá then went on to elaborate on the theme of racial unity to an audience of Blacks and Whites who had rarely, if ever, heard such high praise for an interracial gathering. He said to those gathered that "in the world of humanity it is wise and seemly that all the individual members should manifest unity and affinity." (13. ibid.)

In the midst of a period saturated with toxic racist and anti-Black language, 'Abdu'l-Bahá offered positive racial images woven into a new language of racial unity and fellowship. He painted a picture for his interracial audience: "As I stand here tonight and look upon this assembly, I am reminded curiously of a beautiful bouquet of violets gathered together in varying colors, dark and light." (14. ibid.) To still another racially mixed audience, 'Abdu'l-Bahá commented: "In the clustered jewels of the races may the blacks be as sapphires and rubies and the whites as diamonds and pearls. The composite beauty of humanity will be witness in their unity and blending." (15. ibid.)

Through His words and actions, 'Abdu'l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá'í teachings on racial unity. Several examples stand out. Two Bahá'ís, Ali-Kuli Khan, the Persian charge d'affaires, and Florence Breed Khan, his wife, arranged a luncheon in 'Abdu'l-Bahá's honor in Washington D.C. The guests were members of Washington's social and political elite. Before the luncheon, 'Abdu'l-Bahá sent for Louis Gregory, a lawyer and well-known African American Bahá'í. They chatted for a while, and when lunch was ready and the guests were seated, 'Abdu'l-Bahá invited Gregory to join the luncheon. The assembled guests were no doubt surprised by 'Abdu'l-Bahá's inviting an African American to a White, upper-class social affair, but perhaps even more so by the affection and love 'Abdu'l-Bahá showed for Gregory when He gave him the seat of honor on His right. A biographer of Louis Gregory pointed out the profound significance of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's action: "Gently but yet unmistakably, 'Abdul-Bahá has assaulted the customs of a city that had been scandalized a decade earlier by President's Roosevelt's dinner invitation to Booker T. Washington." (16. Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1982), 53.)

The promotion of interracial marriage was yet another example of how 'Abdu'l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá'í teachings on racial unity. Many states outlawed interracial marriage or did not recognize such unions; yet, 'Abdu'l-Bahá never wavered in his insistence that Black and White Bahá'ís should not only be unified but should also intermarry. Before his visit to the United States, He had first broached the subject in Palestine with several Western Bahá'ís and explored the sexual myths and fears at the core of American racism. His solution was to encourage interracial marriage. Once in the U.S., He demonstrated the lengths to which the American Bahá'í community should go to show its dedication to racial unity when He encouraged the marriage of Louis Gregory and an English Bahá'í, Louisa Mathew. Their marriage was the first Black-White interracial marriage that was personally encouraged by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. This demonstration of Bahá'í teachings proved difficult for some Bahá'ís who doubted that such a union could last in a racially segregated society, but the marriage lasted until the end of the couple's lives, nearly four decades later. Throughout this period, Louis and Louisa became a shining example of racial unity. (17. Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1982), 63-72, 309-10.)

Race Amity Activities: The Bahá'í Community's Responses to Racial Crises, 1921-1937

Although working endlessly to promote racial unity through inspiring talks and actions, 'Abdu'l-Bahá understood the persistent reality of racism in the U.S. In a letter to a Chicago Bahá'í, He predicted what would happen if racial attitudes did not change: "Enmity will be increased day by day and the final result will be hardship and may end in bloodshed." (18. ibid., 59.) Several years later, 'Abdu'l-Bahá repeated this warning to an African American Bahá'í that "if not checked, 'the antagonism between the Colored and the White, in America, will give rise to great calamities.'" (19. ibid., 59.)

Tragically, 'Abdu'l-Bahá's predictions came true. Five years after His visit to the U.S. where He laid the foundation for the American Bahá'í community's future contributions to racial unity, race riots broke out in 1917 in East St. Louis, Illinois, and other cities. Two years later, in 1919, "the greatest period of interracial strife the nation had ever witnessed" (20. John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 313.) rocked the country. From June to the end of the year, there were approximately twenty-five race riots. (21. ibid, 313.) With the country still in the throes of racial upheaval, 'Abdul-Bahá, frail and worn, gathered the strength to rally the American Bahá'í community for what would become one of its signature contributions to racial amity in the U.S. In 1920, He mentioned the tragic state of race relations in the U.S. to a Persian Bahá'í residing in that country: "Now is the time for the Americans to take up this matter and unite both the white and colored races. Otherwise, hasten ye towards destruction! Hasten ye to devastation!" (22. Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1982), 59.)

That same year, 'Abdu'l-Bahá initiated a plan to address the racial crisis in America. As Louis Gregory wrote in his report on the First Race Amity Convention held in Washington, D.C., May 19 to 21, 1921: " It was following His return to the Holy Land…after the World War that 'Abdu'l-Bahá set in motion a plan that was to bring the races together, attract the attention of the country, enlist the aid of famous and influential people and have a far-reaching effect upon the destiny of the nation itself." (23.>Louis Gregory, "Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review," in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 180. Originally published in The Bahá'í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá'í Publishing Committee).) In His message to this first Race Amity Convention, 'Abdu'l-Bahá wrote: "Say to this convention that never since the beginning of time has one more important been held. This convention stands for the oneness of humanity; it will become the cause of the enlightenment of America. It will, if wisely managed and continued, check the deadly struggle between these races which otherwise will inevitably break out." (24. ibid.)

This first race amity convention could not have come at a better time. Ten days later, on May 31 and June 1, a race riot, also known as "the Tulsa race massacre," occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma. "It has been characterized as 'the single worst incident of racial violence in American history'" when "mobs of white residents, many of them deputized and given weapons by city officials, attacked black residents and businesses." (25. Wikipedia, "Tulsa Race Massacre". Available at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre) They not only attacked Blacks on the ground but also used private aircrafts to attack them from the air. The attacks resulted in the destruction of the Black business district known as Black Wall Street, "at the time the wealthiest black community in the United States." (26. ibid.)

One can only imagine what went through the minds of participants in the interracial gathering at that historic first race amity convention in Washington D.C. as the news of the Tulsa race riot swept the nation. Perhaps their minds raced back to a similar but less destructive race riot that had ravaged their own city during the "red summer" (27. John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 314) two years earlier. Some were probably thankful that they were part of a budding interracial movement dedicated to racial amity.

Louis Gregory reflected this optimism after the first race amity convention when he reported: "Under the leadership and through the sacrifices of the Bahá'ís of Washington three other amity conventions…were held….Christians, Jews, Bahá'ís, and people of various races mingled in joyous and serviceable array and the reality of religion shone forth." (28. Louis Gregory, "Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review," in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 182. Originally published in The Bahá'í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá'í Publishing Committee).) He related that "the Washington friends continued their race amity work in another form by organizing an interracial discussion group which continued for many years and did a very distinctive service, both by its activities and its fame as the incarnation as a bright ray of hope amid scenes where racial antagonism was traditionally rife." (29. ibid.)

From the year of the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1921 to 1937, the Bahá'í-inspired race amity movement— a lighthouse of racial hope—cast a sometimes small but powerful beam of light through a thick fog of racism. Notwithstanding setbacks, it made a mighty effort to steady that beam of light. In city after city across the country, brave and courageous peoples of all races and religions joined the movement. In December of 1921, Springfield, Massachusetts, followed Washington D.C. Three years later, New York joined the ranks of race amity workers. That same year Philadelphia—"the City of Brotherly Love" — held its first Race Amity Convention and followed it up six years later (1930) with another one. (30. ibid.)

In 1927, a year Louis Gregory called "that memorable year for amity conferences," (31. Louis Gregory, "Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review," in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 185) a race amity conference was held in Dayton, Ohio. The Dayton community hosted a second race amity conference in 1929. (32.ibid., 186.) According to Gregory, "Race amity conferences at Green Acre, the summer colony of the Bahá'ís in Maine, cover[ed] the decade beginning in 1927," (33. ibid., 186) a decade which he referred to as "this fruitful period," (34. ibid., 187) when Geneva, New York, Rochester, New York, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Boston all contributed their share to the race amity movement. (35. ibid., 192-93) "The friends in Detroit, under the rallying cry, 'New Views on an Old, Unsolved Human Problem,' raised the standard of unity in a conference March 14, 1929." (36. ibid., 193) In Atlantic, City, with only one "active Bahá'í worker in the field," not even the opposition of "the orthodox among the clergy…which unfavorably affected the press" (37. ibid., 193-94) could stem the tide of the race amity movement. On April 19, 1931, assisted by the Bahá'ís of Philadelphia, The Society of Friends, and other organizations, close to four hundred people attended a gathering. (38. ibid., 194) Five months later, in October, the Pittsburgh Bahá'ís arranged a conference. (39. ibid., 195)

Bahá'ís and their friends and associates in Denver, Portland, Seattle, and Los Angeles all joined hands as they expanded the circle of unity beyond Black and White to include Native Americans, Chinese-Americans, and Japanese-Americans. (40. ibid., 195-96.) The Bahá'ís also held interracial dinners and banquets. Such banquets "appeared to give to those who shared them a foretaste of Heaven," (41. ibid., 196.) Gregory wrote. One of the last race amity conferences was held in Cincinnati, Ohio, in April of 1935, and was considered

one of the most interesting and influential of all. The Bahá'ís…having with one mind and heart decided upon such an undertaking, under the guidance of their Spiritual Assembly—the local Bahá'í governing council—proceeded to work the matter out in the most methodical and scientific way. [In addition] they succeeded in laying under the tribute of service some sixteen others noted for welfare and progress. (42. Louis Gregory, "Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review," in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 197.)

The Bahá'í racial amity activities also included three interracial journeys of Black and White Bahá'ís "into the heart of the South." They were inspired by the wishes of Shoghi Effendi, who became of the Head of the Bahá'í Faith after the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and was designated the title "Guardian." (43. ibid., 198.) Interracial teams of two Bahá'í men, Black and White, traveled South in the autumn of 1931, the spring of 1932, and the winter of 1933. "One of the most interesting discoveries of [the 1931 team's] trip was to find the same interest at the University of South Carolina, for Whites, as at Allan University and Benedict College, located in the same City of Columbia, for Colored." (44. ibid., 199.)

The Most Challenging Issue: Preparing the American Bahá'í Community to Become a Model of Racial Unity

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the American Bahá'í community contributed its share to promoting racial unity and to lessening, to some degree, the relentless forces of racism. They brought people together in conferences to discuss delicate racial issues and created intimate spaces, such as banquets and interracial dinners in which to break bread, at a time when sitting down and eating together was the prevailing social taboo. These were no small accomplishments. These experiences seeded future interracial meetings and friendships. More work had to be done, however, before the Bahá'í community could move to the next stage of its contribution to racial unity in the larger society. It had to prepare itself to become, at the very least, a work in progress of a model of racial unity.

Foremost among the Guardian's concerns for the United States was racial prejudice and its influence on the American Bahá'í community. In his lengthy letter to the American Bahá'í community, which was published as The Advent of Divine Justice (1939), he characterized racism as "the corrosion of which, for well-nigh a century has bitten into the fiber, and attacked the whole social structure of American society" and said it should be "regarded as constituting the most vital and challenging issue confronting the Bahá'í community at the present stage of its evolution." He told Bahá'ís of both races that they faced "a long and thorny road beset with pitfalls" that "still remained untraveled." (45. Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/720204804) Both races were assigned specific responsibilities. White Bahá'ís were to

make a supreme effort in their resolve to contribute their share to the solution of this problem, to abandon once for all their usually inherent and at times subconscious sense of superiority, to correct their tendency towards revealing a patronizing attitude towards the members of the other race, to persuade them through their intimate, spontaneous and informal association with them of the genuineness of their friendship and the sincerity of their intentions, and to master their impatience of any lack of responsiveness on a part of a people who have received, for so long a period, such grievous and slow-healing wounds. (46. Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/376777192)

Black Bahá'ís were to "show by every means in their power the warmth of their response, their readiness to forget the past, and their ability to wipe out every trace of suspicion that may still linger in their hearts and minds." (47. ibid.) Neither race could place the burden of resolving the racial problem within the Bahá'í community on the other race or to see it as "a matter that exclusively concerns the other." (48. ibid.)

As well, the Guardian cautioned Bahá'ís that they should not think the problem could be easily or immediately resolved. They should not "wait confidently for the solution of this problem until the initiative has been taken, and the favorable circumstances created, by agencies that stand outside the orbit of their Faith." (49. ibid.) Rather, Shoghi Effendi encouraged Bahá'ís to

believe, and be firmly convinced, that on their mutual understanding, their amity, and sustained cooperation, must depend, more than any other force or organization operating outside the circle of their Faith, the deflection of that dangerous course so greatly feared by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the materialization of the hopes He cherished for their joint contribution to that country's glorious destiny. (50. ibid.)

The American Bahá'í community now had their specific marching orders. During the 1940s, they engaged in a range of efforts designed to eliminate racism and promote unity among its members and continue their decades-old commitment to promote racial unity in the wider society. In 1940, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'í of the United States set the example during its meeting in Atlanta, Georgia — their first meeting in the Deep South. This was timely because the predominantly White Bahá'í community was "far from enthusiastic about putting racial unity into practice." (51. Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1982), 282.) Racially integrated meetings were held for both Bahá'is only and for the general public. (52. ibid., 283.) "White Bahá'ís were put on notice, even at the risk of their withdrawal from the Faith, that they had to come to terms with the principle of oneness both in their Bahá'í community life and in their approach to the public." (53. ibid., 283.) Before long, the Local Spiritual Assembly of the Atlanta Bahá'í community mirrored the interracial makeup of the community. (54. ibid., 283.)

A new generation of Bahá'ís had to be educated about race if the community hoped to play a role in the pursuit of racial justice and racial unity. In a series of articles, a new Race Unity Committee (RUC) began educating the Bahá'í community on "the most challenging issue." The Bahá'í Children Education Committee (CEC) reviewed and recommended to Bahá'í parents a major book on racial attitudes in children. The RUC also suggested Bahá'í books on race relations emphasizing the link between minority history and culture and the work on racial unity. It urged Bahá'í communities to make race unity a topic of consultation at the Nineteen Day Feasts (55. Bahá'í News (January, 1940), 10-12; Bahá'í News (February, 1940), 10; Bahá'í News (October, 1940), 9. In Richard W. Thomas, Racial Unity: An Imperative for Social Progress, (Ottawa, Canada: The Association of Bahá'í Studies, 1993), 140-41.) — community gatherings held once a month on the Bahá'í calendar.

As tens of thousands of southern Blacks migrated to northern industrial centers during World War II, racial tensions and conflicts exploded. On June 20, 1943, the worst race riot of the war period broke out in Detroit, leaving death and destruction in its wake. (56. Dominic J. Capeci, Jr. and Martha Wilkerson, "Layered Violence: The Detroit Rioters of 1943," The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 84, 2 (Jackson, Miss. and London: University Press of Mississippi, 1991). Available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.2307/2649046?journalCode=jnh)

For decades, the Bahá'ís had been warned that such racial turmoil would continue unless racial justice and racial unity were established. So they continued their work. In the fall of 1944, the Bahá'í News claimed, "The past year has reported the most progress in race unity since the movement began." (57. Bahá'í News (September, 1944),7.) In short, as terrible and destructive as race riots and racial injustice could be, they would not dampen the spirit nor hold back the Bahá'í community's mission of promoting racial justice and racial unity.

Responding to the dynamic nature of racism, however, has always required of the Bahá'ís agility and an ability to read the signs of the time and respond accordingly. During World War II, anti-Japanese racism had, for instance, become widespread, and thousands of Japanese Americans were interned in concentration camps. (58. Bill Hosokawa, Nisei, The Quiet Americans, (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1969), 204-48; Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982), 329-405.) Conscious of the dangers of rising xenophobic sentiments, Shoghi Effendi, in December 1945, sent a letter through his secretary to the RUC pointing out that "to abolish prejudice against any and every race and minority group, it is obviously proper to include in particular any group that is receiving especially bad treatment—such as the Japanese-Americans are being subjected to." (59. Bahá'í News (October, 1946), 4.)

A Steady Flow of Guidance on Race Unity: The 1950s and the Turbulent 1960s

In 1953, at the historic All-American Conference celebrating the centenary of the birth of Bahá'u'lláh's revelation, the dedication of the completed Bahá'í Temple in Wilmette, Illinois, and the start of a ten-year plan for the worldwide Bahá'í community to advance its growth and development, Dorothy Baker, a White Bahá'í and veteran race unity worker, had just returned from the Holy Land with a message from the Guardian. The Guardian, she reported, had said

one driving thing over and over—that if we did not meet the challenging requirements of raising to a vast number the believers of the Negro race, disasters would result. And…that it was now for us to arise and reach the Indians of this country. In fact, he went so far as to say on two occasions that this dual task is the most important teaching work on American shores today. (60. Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1982), 292)

Over the years, the predominantly White Bahá'í community had accomplished a great deal in promoting race unity conferences, interracial dinners, and other interracial activities, but times were changing. The state of race relations in the Bahá'í community and the wider society required much more radical action. Shoghi Effendi's instructions to bring in "vast numbers" of African-Americans presented a challenge to many White Bahá'ís. Others probably felt they were already doing enough participating in periodic race unity programs. This level of Bahá'í activity would not, however, raise "to a vast number the believers of the Negro race." Shoghi Effendi instructed the Bahá'ís to establish two committees: one to teach African Americans and another to teach Native Americans. He wanted the Bahá'ís "to reach the Negro minority with this great truth in vast numbers. Not just publicity stunts…" (61. ibid., 293)

Bahá'ís continued to promote racial unity. In 1957, the National Assembly, with the approval of the Guardian, instituted Race Amity Day, to be "observed on the second Sunday of June beginning June 9, 1957." (62. Bahá'í News (May, 1957), 1.) It was established as an exclusively Bahá'í-sponsored event different from Brotherhood Week and Negro History Week, events sponsored by other organizations in which Bahá'ís had participated. The purpose of Race Amity Day was to "celebrate the Bahá'í teachings of the Oneness of Mankind, the distinguishing feature of the Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh." (63.ibid., 1.)

That same year, the Bahá'í Interracial Teaching Committee started holding a race amity meeting in conjunction with the annual observance of Negro History Week. Eighty-three Bahá'í communities in thirty-three states conducted some form of public meeting addressing the concerns of the African-American community. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History distributed Bahá'í literature to its exclusive mailing list of distinguished African Americans. In turn, the committee gave the association 500 copies of "Race and Man," a Bahá'í publication featuring discussions on race. (64. Bahá'í News (April, 1957), 6.)

As well, in 1957, Americans also witnessed as "segregationists cheered the active opposition of Governor Orval Faubus to the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Not until President Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock in response to the governor's defiance of a court order did the Negro children gain admission to the school." (65. John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 436.) The forces of racial justice and race unity prevailed, however, with the passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, "the first civil rights act since 1875." (66. ibid., 438.)

The annual Bahá'í Race Amity Day observances stood out among other "points of light" and hope during the racially volatile period of the 1960s. The decade of the Civil Rights Movement and Black urban rebellion and race riots was also the decade when many predominantly White local Bahá'í communities worked tirelessly to promote racial unity. Years after the first Bahá'í race amity observances, scores of these communities throughout the country, through interracial picnics, panel discussions, media events, and official proclamations, provided people from diverse racial backgrounds with hope and inspiration that racial unity was possible. By 1960, Race Amity Day observances were increasingly being recognized by government officials. For example, in 1967, eleven mayors and one governor officially proclaimed Race Unity Day. (67. For an explanation of the change from "race amity" to "race unity" see Morrison, 275.) Yet, in July of that same year, "Detroit experienced the bloodiest urban disorder and the costliest property damage in U.S. history," when forty-three people died and over one thousand were injured. (68. Joe T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas, Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013), 1.)

Expanding the Circle of Unity: Multiracial Community Building, 1970s and 1980s

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the American Bahá'í community experienced a remarkable increase in the racial and ethnic diversity of its membership. In the early 1970s, thousands of African Americans in rural South Carolina and many in other southern states joined the Bahá'í Faith. (69. American Bahá'í (February, 1971, 1-4; April, 1976, 1).) In 1972, the American Bahá'í Northeast Oriental Teaching Committee began reaching out to Asian American populations of the Northeastern States. (70. Bahá'í News (January, 1973),5.) In 1986, the Interracial Teaching Committee described the great influx of southern rural Blacks as well as other racial groups into the Bahá'í community as an indication of the American Bahá'í community becoming "a truly multiethnic community with fully one-third of its members Black and rural, and a significant percentage from the Native-American, Hispanic, Iranian, and Southeast Asian populations." (71. Bonnie J. Taylor, The Power of Unity: Beyond Prejudice and Racism. Selections from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, the Bab,'Adbu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and the Universal House of Justice, compilation (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1986), ix.)

Bahá'ís were expanding their circle of community, embracing more and more diverse peoples and knitting them into the fabric of their collective life. In 1985, Milwaukee Bahá'ís, in cooperation with the Midtown Neighborhood Association, a social-service agency, and the Hmong-American Friendship Association, worked to serve the needs of the Hmong people in the neighborhood by opening the Bahá'í Center on weekends for adult English classes and after-school classes for culture and language for children ages 8 to 13. (72. American Bahá'í (March, 1985), 8.) In their response to the unprecedented waves of Asian immigrants arriving to America during the 1980s, the American Bahá'í community published guidelines to facilitate the integration of Indo-Chinese refugees into the Bahá'í community.

In 1989, the U.S. Bahá'í Refugee Office visited ten cities throughout central California to help integrate refugees into the larger Bahá'í community. The Bahá'í community did not limit its concern to Bahá'í refugees only. For example, the Bahá'ís in Des Moines, Iowa, resolved to adopt all Cambodian refugees in that state as a service goal for the 1989-90 year. The persecution of Iranian Bahá'ís in Iran during the late 1970s forced many Iranian Bahá'ís to seek refuge in the United States where they were assisted by the Bahá'í Persian-American Committee to become part of the increasingly diverse American Bahá'í community. (73. American Bahá'í (April, 1989), 2.)

The Bahá'í community was becoming what Shoghi Effendi had hoped for a half-century ago when he wrote:

No more laudable and meritorious service can be rendered the Cause of God, at the present hour, than a successful effort to enhance the diversity of the members of the American Bahá'í community by swelling the ranks of the Faith through the enrollment of the members of these races. A blending of these highly differentiated elements of the human race, harmoniously interwoven into the fabric of an all-embracing Bahá'í fraternity, and assimilated through the dynamic process of a divinely appointed Administrative Order and contributing each its share to the enrichment and glory of Bahá'í community life, is surely an achievement the contemplation of which must warm and thrill every Bahá'í heart. (74. Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/138409678)

The 1990s: Models and Visions of Racial Unity and the Los Angeles Riots

The American Bahá'í community entered the 1990s with increased commitment to racial justice and racial unity. The Association for Bahá'í Studies held a conference, "Models of Racial Unity," in November of 1990 to explore examples of racial unity. This conference produced a joint project, "Models of Unity: Racial, Ethnic, and Religious," conducted in the spring of 1991 by the Human Relations Foundation of Chicago and the National Spiritual Assembly to "find examples of efforts that have successfully brought different groups of people together in the Greater Chicago area." (75. Models of Unity: Racial, Ethnic, and Religious. A Project of the Human Relations Foundation of Chicago and the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States, February, 1992.))

The next year, the National Assembly published a statement, "The Vision of Race Unity: America's Most Challenging Issue," as the cornerstone of a national race unity campaign. They distributed it to a wide range of people including teachers, students, organizations, and public officials. In April, 1992, several months after the publication of the joint-project report on Models of Unity in Chicago, the National Assembly sponsored a race unity conference at the Carter Presidential Center in Atlanta, Georgia (76. See conference program, Visions of Race Unity: Race Unity Conference," The Carter Presidential Center, Atlanta, Georgia, Saturday, April 4, 1992. Sponsored by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States.): "The purpose of this conference is to explore specific actions which may be taken by different groups and institutions to establish racial unity as the foundation for the transformation of our society." (77. Quoted in American Bahá'í (July 13, 1992), 1.) Several weeks later, Los Angeles exploded into violence in the wake of the not guilty verdict of four White policemen caught on tape beating Rodney King, a Black motorist. (78. Paul Taylor and Carlos Sanchez, "Bush orders troops into Los Angeles," The Washington Post, May 2, 1992. Available at https//www.washingtonpost.com/archives/politics) It seemed that the Bahá'í community's constant efforts to promote racial unity were "water in the sand" of racial turmoil.

The National Assembly sent a message, on behalf of the U.S. Bahá'í Community, to Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley:

We join you in your appeal to all our fellow-citizens not to be blinded by anger and hate….the American Bahá'í community, faithful to the teachings of its Founder, has worked for the establishment of racial unity in a country blighted by race prejudice that confronts its cherished values, threatens its peace, and poisons the soul of its citizens. (79. American Bahá'í (June 5, 1992).)

The National Spiritual Assembly referred to its recently published statement on race, "The Vision of Race Unity," and informed the mayor of its readiness to share its message with "city authorities, private organizations, and individuals who seek such a solution." (80. ibid.) In addition, the National Assembly presented to the mayor and the city, the Chicago-based study, Models of Unity: Racial, Ethnic, and Religious. Concluding their letter to the mayor, the Assembly left him with this message of hope:

We offer you, Mr. Mayor, our cooperation, and pray that Los Angeles will emerge from its trials more enlightened and dedicated to the realization of the great truth that we are all "the leaves of one tree and the drops of one ocean". (81. ibid.)

The National Assembly then published a letter to President George H. W. Bush that appeared in several national newspapers. It opens:

No American can look with indifference upon the tragedy relentlessly unfolding in our cities. Its causes lie beyond a particular verdict or a particular act of oppression. The fires and deaths in Los Angeles are only symptoms of an old congenital disease eating at the vitals of American society, a disease that has plagued our country ever since slaves were brought from Africa to these shores by their early settlers. (82. The Washington Post, June 15, 1992, A15. Reprinted in American Bahá'í (June 24, 1992), 1.)

The letter described the path of racial progress in American history as a "history of advance and retreat," and, though acknowledging that the solution to the racial problems "is not simple," stated that it is clear that "America has not done enough to demonstrate her commitment to the equality and the unity of races." For this reason, "ever since its inception a century ago the American Bahá'í community has made the elimination of racism one of its principle goals." (83.ibid. 1.) The National Assembly concluded its letter with an appeal:

We appeal to you, Mr. President, and all our fellow citizens, not to turn away from this "most vital and challenging issue." We plead for a supreme effort on the part of the public and private institutions, schools, and the media, business and the arts, and most of all to individual Americans to join hands, accept the sacrifices this issue must impose, show forth the "care and vigilance it demands, the moral courage and fortitude it requires, the tact and sympathy it necessitates" so that true and irreversible progress may be made and the promise of this great country may not be buried under the rubble of our cities. (84.

The National Spiritual Assembly then turned to the Bahá'í community. In mid-May 1992, it met in Atlanta with representatives of twenty-nine local Bahá'í assemblies from the surrounding area and members of Local Spiritual Assemblies in fourteen cities in which rioting had taken place to review the Bahá'í communities' responses to the riots and their aftermath and to consult with an international board of advisers on courses of action. The consultation resulted in a "decision to channel all national effort in the coming year into one mission—the promotion of race unity." (85. American Bahá'í (July 13, 1992), 1.)

For the next four years, Bahá'ís labored on in the diverse and often confusing maze of race relations. They and others were sincere workers in their efforts. Following the long tradition of Bahá'í race unity work, the Bahá'í Spiritual Assembly of Detroit created a task force in 1993 to carry out a faith-based mandate to promote racial unity. Two years later, the task force became a non-profit organization called the "The Model of Racial Unity, Inc." and expanded its membership to include members of the Episcopal Diocese of Detroit and the Catholic Youth Organization. The task force launched its first conference on June 11, 1994, "to promote unity among the diverse populations of Detroit Metropolitan area by bringing together people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds in an atmosphere of cooperation and mutual respect." (86. Joe T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas, Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013), 282.)

A day before the conference, the Detroit Free Press commented: "The Bahá'í Faith Community of Greater Detroit is a main sponsor of the conference, which is an outgrowth of the religion's guiding principles: unity across racial and ethnic lines." (87. Detroit Free Press, June 10, 1994.) The Second Annual Model of Racial Unity Conference in 1995 demonstrated how far the organization had progressed since the first conference. General Motors was now the major sponsor. Other sponsors included the owner of Azar's Oriental Rugs and Mag-Co Co Investigations. Both owners were members of the Metropolitan Bahá'í community—the former, an Iranian American, and the latter, African American. (88. Joe T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas, Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013), 282)

It was a great honor and tribute to the efforts of the Bahá'í community when Mayor Dennis W. Archer designated May 20, 1995, as "Model of Racial Unity Day." The Third Annual Model of Racial Unity Conference occurred on May 18, 1996. (89. ibid., 282) The Bahá'ís attending and participating in that conference and the larger American Bahá'í community would soon be entering a new stage of spiritual guidance on race relations.

Earlier in the year, the House of Justice had advised the Bahá'ís: "With respect to principles, it would assist the friends greatly if the issue of addressing race unity can be formulated within the broad context of the community. The distinctiveness of the Bahá'í approach to many issues needs to be sharpened." Bahá'ís should be "future oriented, to have a clear vision and to think through the steps necessary to bring it into fruition. This is where consultation with the Bahá'í institutions will provide a critical impulse to your own efforts." (9. Universal House of Justice, from a letter dated 25 February, 1996, in Extracts from Letters Written on Behalf of the Universal House of Justice to Individual Believers in the United States on the Topic of Achieving Race Unity (Updated Compilation 1996-2000), [1], 1. Available at https://greenlakebahaischool.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/compilation-uhj-on-race-unity-1996-2020.pdf)

Several months later, the 1996 Ridvan Message provided that "clear vision" stating: "The next four years will represent an extraordinary period in the history of our Faith, a turning point of epochal magnitude…" (91. Universal House of Justice, Ridvan 1996. Available at www.bahai.org/r/328665132) In 1996, a twenty-five year period of intensive learning commenced during which Bahá'í endeavors worldwide have become increasingly focused on capacity building in local populations to take greater ownership of their spiritual, intellectual, and social advancement, opening new possibilities in the long-term effort of the Bahá'ís to root out racial prejudice and contribute to the emergence of a society based on racial justice and unity.

Conclusion

The pursuit of racial justice and unity have been defining aspirations of the Bahá'í community of the United States since the earliest days of its establishment in the country. Indeed, for well over a century, it has dedicated itself to racial unity. During periods of racial turmoil, it has contributed its share to the healing of the nation's racial wounds. 'Abdu'l-Bahá provided the example during his visit in 1912 and set in motion a race amity movement in 1921 for the Bahá'í community to build upon. Bahá'ís continued this work for decades with some fits and starts, but always moving forward under the inspired guidance of the Guardian of the Faith and then the Universal House of Justice.

|

|