|

|

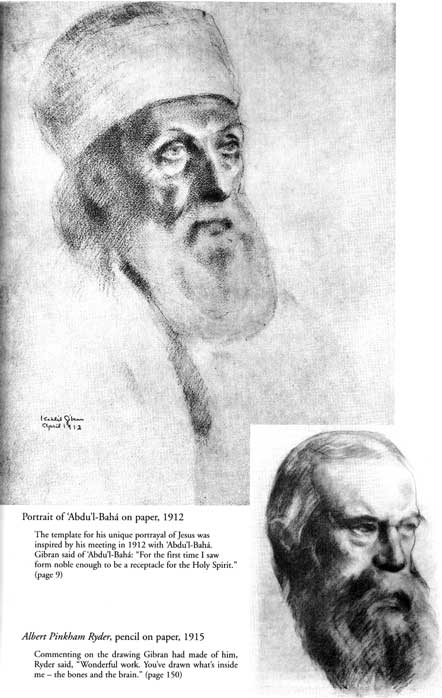

Abstract: Includes portrait of 'Abdu'l-Bahá sketched by Kahlil Gibran. Notes: Pages 9, 123-26, 128, 251-5, 261, 263, 266, plate between 276-277. |

Kahlil Gibran:

Man and Poet

by Suheil Badi Bushrui (published as Suheil Bushrui) and Joe Jenkins

Oxford: Oneworld, 1998[page 9]

Coming from a part of the world that only twenty years before his birth had been convulsed by religious strife, Gibran constantly expressed his conviction that beneath the various forms of religion was an underlying unity. As a student he drew up plans for a Beirut opera house with two domes symbolizing the reconciliation of Christianity and Islam. Although his dream never bore fruit, his writings through the years reflect his desire to merge the Sufi Muslim tradition with the Christian mystical heritage of his background — a dream realized in his portrayal of Almustafa, the eponymous prophet, both a Christ figure and the universal man of Muslim civilization — representing the literary and philosophical meeting-point between the spiritual traditions of East and West.

Every nation has as part of its heritage an inspirational heroic myth. The Irish have the figure of Cuchulain, whose name and mighty deeds are a symbol of national consciousness and aspiration. Christians in Lebanon have Jesus Christ who, as a leader of men, refuses to combat ignorance and intolerance with weapons other than peaceful ones. For Gibran Jesus was the supreme figure of all ages: "My art can find no better resting place than the personality of Jesus. His life is the symbol of Humanity. He shall always be the supreme figure of all ages and in Him we shall always find mystery, passion, love, imagination, tragedy, beauty, romance and truth."62 Gibran saw Christ as a "raging tempest,"63 a depiction that appears in many of his early Arabic writings. The poet's vision of the Nazarene was crystallized too in his English work Jesus, the Son of Man (1928), a book which some critics thought was imbued with an inspirational intensity that even exceeds The Prophet.

While many of his opinions were modified over the years, his fascination with Christ continued throughout his life, and any understanding of Gibran the man and poet will fail unless it explores the deep kinship the man from Lebanon felt with the "commander" from Galilee.

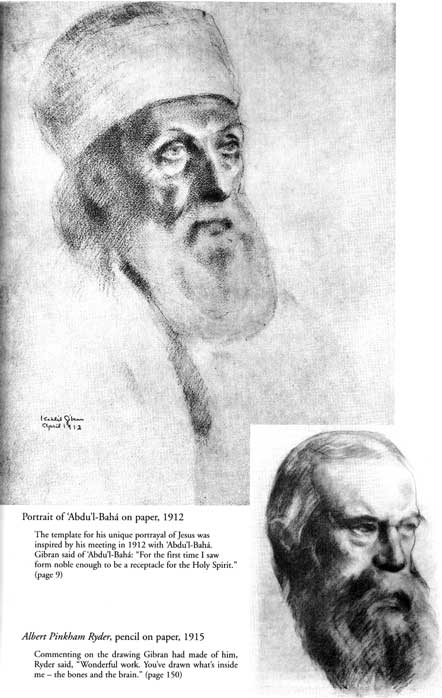

The template for his unique portrayal of Jesus was inspired by his meetings in 1912 with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Bahá'í leader, whom he drew in New York, a man whose presence moved Gibran to exclaim: "For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit. "M His meetings with 'Abdu'l-Bahá left an indelible impression on the poet, surpassing in its influence many propitious acquaintances Gibran made during his years in New York, including Carl Gustav Jung and W. B. Yeats.

62. K.G. to M.H., April 29, 1909, Chapel Hill papers.

63. "The Crucified," in A Treasury, 154.

[pages 123-26]

During the winter of 1912 Gibran reveled in his solitude: "While ones heart is being transformed into a little world, one wants to be alone."103 Often his work so absorbed him that he hardly ate, enjoying these unconsciously self-imposed periods of fasting.104 In the periods of his life when he was taken out to dine by friends, he would afterwards give himself "a spot of fasting, to overcome what they, in their affection," had done to him.105 Work and food together, as far as he was concerned, did not appeal to his constitution106 and during these periods of abstinence he felt he was able to work "with burning hands."107 Throughout his life, however, his working habits did little to improve an already weakened constitution. Sometimes he would hardly eat anything all day, only drinking strong Turkish coffee and smoking heavily. Other days he might have an orange for breakfast or a piece of fruit for lunch, never eating anything between these meager pickings. His sleeping patterns too, were sporadic, sometimes from four in the morning to eleven, finding he did his best work between midnight and four.108

These habits, however, took their toll on his health and by February his "old friend the Grippe" had returned.109 He found his body heavy and subject to intense fevers, making him mentally restless:

Juliet Thompson, a Virginian by birth, was related to Edward Fitzgerald, translator of The Rubáiyát. A Celt, from a long line of Irish bards, Juliet's charismatic personality attracted many visitors of all races, creeds, and colors to her nearby apartment at 48 West Tenth Street. Her father, Ambrose White Thompson, had been a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and Juliet's beauty, charm, and artistic gifts later carried his daughter too into the White House.111

Juliet was a follower of the Bahá'í faith, with which Gibran was acquainted. She had lent him some of the Arabic works of the founder Bahá'u'lláh,112 whose message of unity and the essential truths common to all the world religions struck an answering chord with Gibran's own beliefs. Gibran later declared that Bahá'u'lláh's Arabic writings were the most "stupendous literature that ever was written."113 Auspiciously, the spiritual leader of the Bahá'ís and chief expounder of the faith, 'Abdu'l-Bahá,114 was due to visit New York that April and Juliet asked Kahlil Gibran to paint his portrait.

In later years Juliet spoke of Gibran's paintings as being "mysterious and poetic," and said of him: "He had a high, delicate voice and an almost shyly modest manner, until he came out with something thundering.., he was the spitting image of Charlie Chaplin, I used to tell him so. It made him frightfully mad... He was very modest and retiring in his personal life."115 The honor of being given the commission to draw 'Abdu'l-Bahá (referred to by Bahá'ís as "the Master") can only be appreciated by observing the devotion Juliet felt toward "the Master."

Over the coming days Juliet observed how, as 'Abdu'l-Bahá walked among the people or addressed the poor at the Bowery mission,117 all eyes would follow "His scintillating power" and "strange, unearthly majesty."118 Those who met him perceived no more than their capacity could register, and even the skeptical Turkish ambassador Zia Pasha toasted him as "the Light of the age, Who has come to spread His glory and perfection among us."119

It was with great anticipation then that Gibran awaited the fruition of Juliet's plans to arrange a sitting, and he wrote to Mary: "I must draw 'Abdu'l-Bahá. His portrait is as necessary to my series as that of Rodin."120 Mary reassured him: "He will be drawn by you — he will understand your series and you, and it will be his pleasure as well as yours."121

Gibran met and talked with 'Abdu'l-Bahá three times before the sitting, even acting as his interpreter for the many visitors who flocked to see their Master.122 Gibran said of him: "He is a very great man. He is complete. There are worlds in his soul. And oh what a remarkable face — what a beautiful face — so real and so sweet."123

Finally a sitting was arranged on Friday April 19 at seven-thirty in the morning, yet despite the "early hour," Gibran felt sure he was capable of "making a great drawing of him."124 The artist slept badly the night before, sensing the air charged with the horrible sea tragedy of the White Star liner Titanic which had sunk on April 14-15125 off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland with the loss of 1,513 lives.126 He began his work at eight, and after an hour the twenty-five people in the room began to shake his hands, saying: "You have seen the soul of the Master." 'Abdu'l-Bahá then spoke to Gibran in Arabic: "Those who work with the Spirit work well. You have the power of Alláh in you," and, quoting Mohammed, said: "Prophets and poets see with the light of God," Gibran recording that in 'Abdu'l-Bahá's smile "there was the mystery of Syria and Arabia and Persia."127

Juliet Thompson later recalled that when Gibran wrote his portrait of Christ, Jesus, the Son of Man, he had told her that his meetings with the Bahá'í leader had profoundly influenced his work.128 These meetings left an indelible impression, and Gibran wrote that he had "seen the Unseen, and been filled";129 Mary, on seeing a smaller sketch he had made of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's face, wrote: "In it you have set the timeless light and the eye at rest on Reality. Men will see there what they desire: that real things are; and they will be comforted and strengthened."130

In the days that followed his meeting, Gibran experienced what he called "something cyclonic... something moving as the mighty elements move. His life felt full and expansive: "Models to be studied, poems to be written, thoughts to be imprisoned, dreams to be gazed at and gracious people to whom I must show my work."131

These were exciting times for Gibran. His recently published The Broken Wings was receiving glowing reviews in the Arab world: "a wonderful work of art," "perhaps the most beautiful in modern Arabic," "a tragedy of subtlest simplicity."132

103. K. G. to M. H., January 26, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

104. B.P., 58.

105. Young, This Man from Lebanon (1945), 29.

106. B.P., 88.

107. K. G. to M. H., January 31, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

108. B.P., 87-88.

109. Ibid., 64.

110. Ibid., 66.

111. Thompson, Diary, xviii.

112. Bahá'u'lláh (1817-92), the founder of the Bahá'í faith.

113. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 229.

114. 'Abdu'l-Bahá (1844-1921), the expounder of the Bahá'í faith.

115. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 229.

116. Thompson, Diary, 234-35.

117. 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at the Bowery mission on April 19 (see 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 32-34).

118. Honnold, Vignettes, 158.

119. Thompson, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, 21-22.

120. K. G. to M. H., April 10, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

121. M. H. to K. G., April 11, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

122. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

123. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

124. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

125. B.P., 74.

126. See, e.g., Upshall (ed.), The Hutchinson Encyclopedia, 838.

127. B.P., 74.

128. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 228.

129. K. G. to M. H., April 19, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

130. M. H. to K. G., April 24, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

131. K. G. to M. H., May 3, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

132. K. G. to M. H., May 6, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

[page 128]

In May 1912 Gibran visited the Metropolitan Museum and was thrilled to see the newly acquired work of his artistic mentor, Rodin: "It expresses the two sides of his genius; the exquisite loneliness and the powerful strangeness. The two heroic figures of Adam and Eve particularly impressed him, and he felt that Rodin was under the direct influence of Michelangelo when he modeled his Adam.142

Although Gibran would have wished once more to meet 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who was visiting Boston at the time, his own work in New York held him there — finishing new pictures and trying to arrange for Thomas Edison ("he is so representative of America")143 to pose for him.

142. K. G. to M. H., May 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

143. K. G. to M. H., May 20, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

[pages 251-55]

Gibran's portrait, captured in Jesus, the Son of Man, evolved in his many writings over the years.89 It is significant and moving that he decided to complete his testament while his own life was beginning to ebb away. The idea of the book had been nourished for over twenty years, drawing its power from Gibran's readings and contemplations, and his childhood memories, when the language of the Bible and the electrifying figure of the Nazarene filled the consciousness of the Maronire boy from the mountain.

The semi-autobiographical heroes of his early Arabic period, Khalil the heretic and Yuhanna the madman, are insistent that Jesus' mission never consisted in establishing hierarchical institutions with structures and sanctions, but rather in awakening humanity to its own cosmic potentiality.90 Christ as revolutionary inspires Gibran's fearless heroes in their struggles against the violators of his spirit, particularly the power-possessing priest.91 In these early works, and in a later one entitled "The Crucified," Gibran was intent on portraying Christ's "tremendous personal power":92

He also depicts the Nazarene in his prose-poem "Eventide of the Feast" as "the Son of Man" who is "a stranger wandering from East to West," an outsider who has "no place to rest His head."94

Gibran's passion was also expressed in many of his paintings, and when he gave Mary The Crucified in 1920 she exclaimed: "It is so terrible in its pain that talking about it seems like talking about a soul in torture. It's the most beautiful, the most appealing, the most rebuking, wonderful, and dearest thing I ever had. It is the Heart unveiled."95 Gibran had said of his picture Christ's Head that it was nearer to his heart than any other picture he had ever drawn.96

He now turned to what was to be his most ambitious work in English.97 With an advance of $2,000 from Knopf, he settled down, on November 12, 1926,98 to write Jesus, the Son of Man. As he began his book he told Mikhail Naimy that he was "sick and tired" of those who portrayed Jesus as a "sweet lady with a beard," and weary of "scholars" arguing about "the historicity of his personality." For Gibran, Jesus was the most "real personality" in human history, "a man of might and will, a man of charity and pity. He was far from being lowly and meek. Lowliness is something I detest; while meekness to me is but a phase of weakness."99

Any author's portrait, like that of an artist, is dependent upon the existence of a model. For Gibran, the inspiration and template for his unique portrait of Christ was provided by the indelible impression left on him by 'Abdu'l-Bahá100 in 1912, which moved Gibran to exclaim: "For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit."101 Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í faith, had pronounced his eldest son 'Abdu'l-Bahá to be the perfect exemplar of his teachings, the infallible interpreter of his word, and his successor as head of the faith. Born in 1844, in Tehran, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had, as a child, recognized his father's great station, but on becoming head of the faith was the victim of much jealousy and opposition. A prisoner for forty years in the fortress city of Akka in the Holy Land, he was finally liberated when the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 deposed sultan Abdu'l-Hamid and set free all those in the Ottoman empire who had been imprisoned for their religious beliefs. Widely respected by religious leaders and politicians worldwide, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was later knighted by the British for the part he played in alleviating the famine in the Holy Land during World War I. He began to carry the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh to the West, and between 1911 and 1913 he visited Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, the United States, and Canada. Central to his message to the people of America — a message echoed by Gibran himself — was the realization of unity in diversity:

During his nine-month visit to the United States and Canada — a strenuous tour that saw him traveling constantly up and down the Eastern seaboard into the Chicago heartland and traversing the continent via Montreal, Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Denver to the West Coast before returning to New York — he expounded the fundamental principles of the revelation and teachings of Bahá'u'lláh. He spoke of the equality between men and women, the harmony of science and religion, the need for universal education and a universal language, the independent investigation of truth, the oneness of God, the oneness and continuity of the prophets of God, the oneness of the human race and the elimination of all forms of prejudice and discrimination. The American press gave his tour extensive coverage and his speeches were widely circulated in the daily press. Gibran avidly followed the news of one whom he ardently desired to draw.

'Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to the United States took place just before the outbreak of a war that was to claim ten million lives and maim millions more. He foresaw the cataclysm ahead: "Just now Europe is a battlefield of ammunition, ready for a spark and one spark will set aflame the whole world," and he called for America to raise "the standard of international peace, maintaining that no other country had "greater capacity for such an initial step."103

After being drawn by Gibran on April 19, 1912, 'Abdu'l-Bahá delivered two speeches at Columbia University and at the Bowery mission in New York where he proclaimed his message of unity:

Speaking at churches, universities, sanatoriums, literary societies, and synagogues, and addressing Christians, Bahá'ís, Jews, Esperantists, suffragettes, theosophists, students, the sick, and the poor, he often made references to Christ. Gibran, who heard him address an audience at the Astor hotel in New York, found his own reflections on Jesus being in accord with the views being expressed by this great spiritual teacher from the East:

Such ideas resonated with Gibran, particularly Abdu'l-Bahá's teachings on the equality of men and women, a theme Gibran was to address in Jesus, the Son of Man. 'Abdu'l-Bahá asserted that men and women must be treated as equals if humanity is to progress:

He also spoke about terrible conflicts that had erupted between Christians and Muslims, and in a speech in Brooklyn107 expressed his belief in the essential oneness of religion.108

Gibran's own condemnation of fanaticism, forged in the crucible of his own country's bloody history, was in accord with 'Abdu'l-Bahá's belief Quoting Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke of the horrors of religious prejudice and sectarian hatred:

Gibran was captivated by 'Abdu'l-Bahá calling him "complete. There are worlds in his soul";11O and he was enthralled and electrified by his life-affirming message:

III

Gibran wrote most of Jesus, the Son of Man in Boston — away from the pressures of New York — staying with Marianna. Although he was overjoyed to be absorbed again in a project so close to his heart, his creative endeavors continued to be punctuated by periods of ill health;112 his new amanuensis, Barbara Young, noted the turbulence the poet had to endure while writing the book — as though he "had come through a mighty and terrible struggle."113

When he finally completed his first manuscript it was his longest work. Employing an original scheme — which has been likened to Robert Browning's method in The Ring and the Book114 — Gibran presents seventy-eight different impressions of Jesus imaginatively attributed to his contemporaries, both real and fictitious; "His words and deeds as told and recorded by those who knew Him."

His vision of Christ, as it emerges through these imaginary accounts, is poetical and highly unorthodox, with no pretensions to historical accuracy.115 His Jesus is not born of a virgin, he does not die for our salvation, nor is he resurrected. His miracles are the result of natural phenomena, and he teaches the doctrine of reincarnation, Gibran placing him in the context of other avatars who have walked the earth:

89. "When I meditated upon Jesus I always saw Him either as an infant in the manger seeing His mother Mary's face for the first time, or staring from the crucifix at His mother's face for the last time" (Spiritual Sayings [1963], 27).

90. In "The Crucified" Gibran writes: "Jesus was nor sent here to teach the people to build magnificent churches and temples. He came to make the human heart a temple, and the soul an altar, and the mind a priest" (Secrets of the Heart [1992], 215).

91. In "Khalil the Heretic" Gibran writes of the priest: "He is a hypocrite whom the faithful girded with a fine crucifix which he held above their heads as a sharp sword" (Spirits Rebellious, 103).

92. B.P., 363.

93. "The Crucified," in Secrets of the Heart, 214.

94. "Eventide of the Feast," in ibid., 226.

95. B.P., 338.

96. Ibid., 340.

97. J. and K. Gibran, Life and World, 384.

98. Young, This Man from Lebanon(1945), 102.

99. Naimy, A Biography, 208.

100. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 228.

101. Honnold (ed.), Vignettes, 158.

102. Talk delivered at reception at Metropolitan Temple, Seventh Avenue and Fourteenth Street, New York, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, May 28, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 151.

103. Talk delivered at meeting of International Peace Forum, Grace Methodist Episcopal Church, West 104 Street, New York, by 'Abdul Bahá, May 12, 1912, in ibid., 122, 121.

104. Talk delivered at Earl Hall, Columbia University, New York, by Abdu'l-Bahá, April 19, 1912, in ibid., 32.

105. Talk delivered at Central Congregational Church, Brooklyn, New York, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, June 16, 1912, in ibid., 199, 200.

106. Talk delivered at Hotel Sacramento, California, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Oct. 25, 1912, in ibid., 375.

107. Talk delivered at the Central Congregational Church, Hancock Street, Brooklyn, New York, by Abdu'l-Bahá, June 16,1912, in ibid., 200, 201, 202.

108. "A Poet's Voice," in A Tear and a Smile (1994), 192.

109. Talk delivered at Green Acre, Eliot, Maine, by Abdu'l-Bahá, Aug. 17, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 266.

110. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

111. Talk delivered at Green Acre, Eliot, Maine, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Aug. 17, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 262-63.

112. A Self-Portrait (1972), 84.

113. Young, This Man from Lebanon (1945), 102-103.

114. Both John Haynes Holmes, the former minister of the Community Church in New York (quoted in J. and K. Gibran, Life and World 390), and Claude Bragdon (in "Modern Prophet from Lebanon," Merely Players, 144) compare Gibran's work with Browning's.

115. Some scholars, such as Joseph Ghougassian, argue that the exegesis, the thinking, and deeds of Gibran's Jesus concur with Christ's personality as depicted by the four evangelists (Wings of Thought, 221).

116. Jesus, the Son of Man, 42, 43.

[page 261]

Jesus' awesome power, a recurrent theme in the book, is described by an unnamed man from the desert: "Men and women fled from before His face, and He moved amongst them as the whirling wind moves on the sand-hills."164 Others portray him as a man who could be patient as "a mountain in the wind," yet also impatient of "men of cunning", a man who "would not be governed."165

Those who heard him speak remembered the beauty and passion of his oratory. Assaph, himself an orator from Tyre, perceived that "when you heard Him your heart would leave you and go wandering into regions not yet visited."166 At her wedding in Cana, Rafca the bride remembered that "His voice enchanted us so that we gazed upon Him as if seeing visions,"167 and a character named Cleopas of Bethroune says, "His voice was like cool water in a land of drought."168

Susannah of Nazareth describes Mary, mother of Jesus, as she awaits her sons imminent death on Good Friday: "At dawn she was still standing among us, like a lone banner in the wilderness wherein there are no hosts."169 Gibran constantly expresses his wonder at the beauty and mystery of womanhood: "Woman shall be forever the womb and the cradle but never the tomb."170 His reverence toward woman, a theme that permeates many of his works, reaches its profoundest and most moving expression in Jesus, the Son of Man, reflecting Gibran's love for the many women in his own life. He had once said to Mary: "Woman has deeper mind that is hers only. We call it intuition. And man uses woman's intuition... Women are better than men. They are kinder, more sensitive, more stable, and have a finer sense about much of life."171 These views bear a striking resemblance to the teachings of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who called women "more tender-hearted, more receptive," possessing "intuition more intense" than men.172

164. Ibid., 89.

165. Ibid., 171.

166. Ibid., 10.

167. Ibid., 30.

168. Ibid., 70.

169. Ibid., 162.

170. Ibid., 167.

171. B.P., 413, 286.

172. Abdu'l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 161.

[page 263]

Echoing his own lifelong belief that Jesus was "the Master Poet," Gibran describes Jesus thus: "Aye, He was a poet whose heart dwelt in a bower beyond the heights... the sovereign of all poets,"185 and in the last essay writes: "Master, Master Poet, Master of our silent desires, The heart of the world quivers with the throbbing of your heart. But it burns not with your song."186

In what is often an unconventional portrayal, Jesus is depicted as having traveled to lands both in the East and the West: Philemon, a Greek apothecary, depicts him as "the Master Physician" who visited India where "the priests revealed to Him the knowledge of all that is hidden in the recesses of our flesh." Again the influence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who called Jesus "the real Physician," is evident — a "physician" who came to heal the world.187Reflecting Gibran's own holistic views on medicine, Philemon witnesses in Jesus a supreme spiritual healer to whom the sacred secrets of another age have been revealed...

185. Jesus, the Son of Man, 80.

186. Ibid., 215.

[page 266]

Was Gibran a Christian? There is no doubt that he had accepted the Christian revelation, taking Jesus as an exemplar and the Bible as a treasury of revealed spiritual and moral truth. However, true to the followers of the Sufi path, he could not accept Christianity as exclusive.215 His was a firm belief in the unity of religion and the unity of being which directed his enthusiastic attention to universal ecumenicalism. His creed involved a diversity of strands of belief: the Upanishads; Syrian Neoplatonism; Judeo-Christian mysticism; Islamic Sufism; and the Bahá'í teachings on universal love and the unity of religion as he heard them from 'Abdu'l-Bahá To these influences can be added those spiritual elements he gleaned from his reading of Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, Ibn al-Farid, and al-Ghazali. He forged his own personal spiritual philosophy in which he would connect all the traditions and join William Blake in declaring that "all religions are one."

215. Jenkins, Christianity, 66-67.

[plate between pages 276-277]

click for larger image

Coming from a part of the world that only twenty years before his birth had been convulsed by religious strife, Gibran constantly expressed his conviction that beneath the various forms of religion was an underlying unity. As a student he drew up plans for a Beirut opera house with two domes symbolizing the reconciliation of Christianity and Islam. Although his dream never bore fruit, his writings through the years reflect his desire to merge the Sufi Muslim tradition with the Christian mystical heritage of his background — a dream realized in his portrayal of Almustafa, the eponymous prophet, both a Christ figure and the universal man of Muslim civilization — representing the literary and philosophical meeting-point between the spiritual traditions of East and West.

Every nation has as part of its heritage an inspirational heroic myth. The Irish have the figure of Cuchulain, whose name and mighty deeds are a symbol of national consciousness and aspiration. Christians in Lebanon have Jesus Christ who, as a leader of men, refuses to combat ignorance and intolerance with weapons other than peaceful ones. For Gibran Jesus was the supreme figure of all ages: "My art can find no better resting place than the personality of Jesus. His life is the symbol of Humanity. He shall always be the supreme figure of all ages and in Him we shall always find mystery, passion, love, imagination, tragedy, beauty, romance and truth."62 Gibran saw Christ as a "raging tempest,"63 a depiction that appears in many of his early Arabic writings. The poet's vision of the Nazarene was crystallized too in his English work Jesus, the Son of Man (1928), a book which some critics thought was imbued with an inspirational intensity that even exceeds The Prophet.

While many of his opinions were modified over the years, his fascination with Christ continued throughout his life, and any understanding of Gibran the man and poet will fail unless it explores the deep kinship the man from Lebanon felt with the "commander" from Galilee.

The template for his unique portrayal of Jesus was inspired by his meetings in 1912 with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Bahá'í leader, whom he drew in New York, a man whose presence moved Gibran to exclaim: "For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit. "M His meetings with 'Abdu'l-Bahá left an indelible impression on the poet, surpassing in its influence many propitious acquaintances Gibran made during his years in New York, including Carl Gustav Jung and W. B. Yeats.

62. K.G. to M.H., April 29, 1909, Chapel Hill papers.

63. "The Crucified," in A Treasury, 154.

[pages 123-26]

During the winter of 1912 Gibran reveled in his solitude: "While ones heart is being transformed into a little world, one wants to be alone."103 Often his work so absorbed him that he hardly ate, enjoying these unconsciously self-imposed periods of fasting.104 In the periods of his life when he was taken out to dine by friends, he would afterwards give himself "a spot of fasting, to overcome what they, in their affection," had done to him.105 Work and food together, as far as he was concerned, did not appeal to his constitution106 and during these periods of abstinence he felt he was able to work "with burning hands."107 Throughout his life, however, his working habits did little to improve an already weakened constitution. Sometimes he would hardly eat anything all day, only drinking strong Turkish coffee and smoking heavily. Other days he might have an orange for breakfast or a piece of fruit for lunch, never eating anything between these meager pickings. His sleeping patterns too, were sporadic, sometimes from four in the morning to eleven, finding he did his best work between midnight and four.108

These habits, however, took their toll on his health and by February his "old friend the Grippe" had returned.109 He found his body heavy and subject to intense fevers, making him mentally restless:

I simply can't relax. My mind is like a brook, always running, always seeking, always murmuring. I was born with an arrow in my heart, and it is painful to pull it and painful to leave it... I live so much within myself, like an oyster. I am an oyster trying to form a pearl of my own heart. But they say that a pearl is nothing but the disease of the oyster.110The coming of spring in 1912 lifted his malaise. He began to reacquaint himself with New York's bustling social life. Small groups of people began visiting his studio to view his work, including the artist Adele Watson, sculptor Ronald Hinton Perry and patron of the arts Marjorie Morten. These fellow artists were appreciative of Gibran's paintings and drawings, and one, Juliet Thompson, proclaimed that his work made "her heart weep." Gibran appreciated such a remark by this talented woman who had once been commissioned to paint a portrait of the American president Woodrow Wilson.

Juliet Thompson, a Virginian by birth, was related to Edward Fitzgerald, translator of The Rubáiyát. A Celt, from a long line of Irish bards, Juliet's charismatic personality attracted many visitors of all races, creeds, and colors to her nearby apartment at 48 West Tenth Street. Her father, Ambrose White Thompson, had been a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and Juliet's beauty, charm, and artistic gifts later carried his daughter too into the White House.111

Juliet was a follower of the Bahá'í faith, with which Gibran was acquainted. She had lent him some of the Arabic works of the founder Bahá'u'lláh,112 whose message of unity and the essential truths common to all the world religions struck an answering chord with Gibran's own beliefs. Gibran later declared that Bahá'u'lláh's Arabic writings were the most "stupendous literature that ever was written."113 Auspiciously, the spiritual leader of the Bahá'ís and chief expounder of the faith, 'Abdu'l-Bahá,114 was due to visit New York that April and Juliet asked Kahlil Gibran to paint his portrait.

In later years Juliet spoke of Gibran's paintings as being "mysterious and poetic," and said of him: "He had a high, delicate voice and an almost shyly modest manner, until he came out with something thundering.., he was the spitting image of Charlie Chaplin, I used to tell him so. It made him frightfully mad... He was very modest and retiring in his personal life."115 The honor of being given the commission to draw 'Abdu'l-Bahá (referred to by Bahá'ís as "the Master") can only be appreciated by observing the devotion Juliet felt toward "the Master."

No words could describe His ineffable peace . . . For at last we saw divinity incarnate. Divinely He turned His head from one child to the other, one group to another. I wish I could picture that turn of the head — an oh, so tender turn, with that indescribable heavenly grace caught by Leonardo da Vinci in his Christ of the Last Supper (in the study for the head) — but in 'Abdu'l-Bahá irradiated by smiles and a lifting of those eyes filled with glory, which even Leonardo, for all his mystery, could not have painted. The very essence of compassion, the most poignant tenderness is in that turn of the head.116

Over the coming days Juliet observed how, as 'Abdu'l-Bahá walked among the people or addressed the poor at the Bowery mission,117 all eyes would follow "His scintillating power" and "strange, unearthly majesty."118 Those who met him perceived no more than their capacity could register, and even the skeptical Turkish ambassador Zia Pasha toasted him as "the Light of the age, Who has come to spread His glory and perfection among us."119

It was with great anticipation then that Gibran awaited the fruition of Juliet's plans to arrange a sitting, and he wrote to Mary: "I must draw 'Abdu'l-Bahá. His portrait is as necessary to my series as that of Rodin."120 Mary reassured him: "He will be drawn by you — he will understand your series and you, and it will be his pleasure as well as yours."121

Gibran met and talked with 'Abdu'l-Bahá three times before the sitting, even acting as his interpreter for the many visitors who flocked to see their Master.122 Gibran said of him: "He is a very great man. He is complete. There are worlds in his soul. And oh what a remarkable face — what a beautiful face — so real and so sweet."123

Finally a sitting was arranged on Friday April 19 at seven-thirty in the morning, yet despite the "early hour," Gibran felt sure he was capable of "making a great drawing of him."124 The artist slept badly the night before, sensing the air charged with the horrible sea tragedy of the White Star liner Titanic which had sunk on April 14-15125 off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland with the loss of 1,513 lives.126 He began his work at eight, and after an hour the twenty-five people in the room began to shake his hands, saying: "You have seen the soul of the Master." 'Abdu'l-Bahá then spoke to Gibran in Arabic: "Those who work with the Spirit work well. You have the power of Alláh in you," and, quoting Mohammed, said: "Prophets and poets see with the light of God," Gibran recording that in 'Abdu'l-Bahá's smile "there was the mystery of Syria and Arabia and Persia."127

Juliet Thompson later recalled that when Gibran wrote his portrait of Christ, Jesus, the Son of Man, he had told her that his meetings with the Bahá'í leader had profoundly influenced his work.128 These meetings left an indelible impression, and Gibran wrote that he had "seen the Unseen, and been filled";129 Mary, on seeing a smaller sketch he had made of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's face, wrote: "In it you have set the timeless light and the eye at rest on Reality. Men will see there what they desire: that real things are; and they will be comforted and strengthened."130

In the days that followed his meeting, Gibran experienced what he called "something cyclonic... something moving as the mighty elements move. His life felt full and expansive: "Models to be studied, poems to be written, thoughts to be imprisoned, dreams to be gazed at and gracious people to whom I must show my work."131

These were exciting times for Gibran. His recently published The Broken Wings was receiving glowing reviews in the Arab world: "a wonderful work of art," "perhaps the most beautiful in modern Arabic," "a tragedy of subtlest simplicity."132

103. K. G. to M. H., January 26, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

104. B.P., 58.

105. Young, This Man from Lebanon (1945), 29.

106. B.P., 88.

107. K. G. to M. H., January 31, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

108. B.P., 87-88.

109. Ibid., 64.

110. Ibid., 66.

111. Thompson, Diary, xviii.

112. Bahá'u'lláh (1817-92), the founder of the Bahá'í faith.

113. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 229.

114. 'Abdu'l-Bahá (1844-1921), the expounder of the Bahá'í faith.

115. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 229.

116. Thompson, Diary, 234-35.

117. 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at the Bowery mission on April 19 (see 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 32-34).

118. Honnold, Vignettes, 158.

119. Thompson, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, 21-22.

120. K. G. to M. H., April 10, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

121. M. H. to K. G., April 11, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

122. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

123. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

124. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

125. B.P., 74.

126. See, e.g., Upshall (ed.), The Hutchinson Encyclopedia, 838.

127. B.P., 74.

128. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 228.

129. K. G. to M. H., April 19, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

130. M. H. to K. G., April 24, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

131. K. G. to M. H., May 3, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

132. K. G. to M. H., May 6, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

[page 128]

In May 1912 Gibran visited the Metropolitan Museum and was thrilled to see the newly acquired work of his artistic mentor, Rodin: "It expresses the two sides of his genius; the exquisite loneliness and the powerful strangeness. The two heroic figures of Adam and Eve particularly impressed him, and he felt that Rodin was under the direct influence of Michelangelo when he modeled his Adam.142

Although Gibran would have wished once more to meet 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who was visiting Boston at the time, his own work in New York held him there — finishing new pictures and trying to arrange for Thomas Edison ("he is so representative of America")143 to pose for him.

142. K. G. to M. H., May 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

143. K. G. to M. H., May 20, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

[pages 251-55]

Gibran's portrait, captured in Jesus, the Son of Man, evolved in his many writings over the years.89 It is significant and moving that he decided to complete his testament while his own life was beginning to ebb away. The idea of the book had been nourished for over twenty years, drawing its power from Gibran's readings and contemplations, and his childhood memories, when the language of the Bible and the electrifying figure of the Nazarene filled the consciousness of the Maronire boy from the mountain.

The semi-autobiographical heroes of his early Arabic period, Khalil the heretic and Yuhanna the madman, are insistent that Jesus' mission never consisted in establishing hierarchical institutions with structures and sanctions, but rather in awakening humanity to its own cosmic potentiality.90 Christ as revolutionary inspires Gibran's fearless heroes in their struggles against the violators of his spirit, particularly the power-possessing priest.91 In these early works, and in a later one entitled "The Crucified," Gibran was intent on portraying Christ's "tremendous personal power":92

The Nazarene was not weak! He was strong and is strong! But the people refuse to heed the true meaning of strength. . . He lived as a leader: He was crucified as a crusader; He died with a heroism that frightened His killers and tormentors. Jesus was not a bird with broken wings; He was a raging tempest who broke all crooked wings.93

He also depicts the Nazarene in his prose-poem "Eventide of the Feast" as "the Son of Man" who is "a stranger wandering from East to West," an outsider who has "no place to rest His head."94

Gibran's passion was also expressed in many of his paintings, and when he gave Mary The Crucified in 1920 she exclaimed: "It is so terrible in its pain that talking about it seems like talking about a soul in torture. It's the most beautiful, the most appealing, the most rebuking, wonderful, and dearest thing I ever had. It is the Heart unveiled."95 Gibran had said of his picture Christ's Head that it was nearer to his heart than any other picture he had ever drawn.96

He now turned to what was to be his most ambitious work in English.97 With an advance of $2,000 from Knopf, he settled down, on November 12, 1926,98 to write Jesus, the Son of Man. As he began his book he told Mikhail Naimy that he was "sick and tired" of those who portrayed Jesus as a "sweet lady with a beard," and weary of "scholars" arguing about "the historicity of his personality." For Gibran, Jesus was the most "real personality" in human history, "a man of might and will, a man of charity and pity. He was far from being lowly and meek. Lowliness is something I detest; while meekness to me is but a phase of weakness."99

Any author's portrait, like that of an artist, is dependent upon the existence of a model. For Gibran, the inspiration and template for his unique portrait of Christ was provided by the indelible impression left on him by 'Abdu'l-Bahá100 in 1912, which moved Gibran to exclaim: "For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit."101 Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í faith, had pronounced his eldest son 'Abdu'l-Bahá to be the perfect exemplar of his teachings, the infallible interpreter of his word, and his successor as head of the faith. Born in 1844, in Tehran, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had, as a child, recognized his father's great station, but on becoming head of the faith was the victim of much jealousy and opposition. A prisoner for forty years in the fortress city of Akka in the Holy Land, he was finally liberated when the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 deposed sultan Abdu'l-Hamid and set free all those in the Ottoman empire who had been imprisoned for their religious beliefs. Widely respected by religious leaders and politicians worldwide, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was later knighted by the British for the part he played in alleviating the famine in the Holy Land during World War I. He began to carry the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh to the West, and between 1911 and 1913 he visited Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, the United States, and Canada. Central to his message to the people of America — a message echoed by Gibran himself — was the realization of unity in diversity:

The sun is one but the dawning-points of the sun are numerous and changing. The ocean is one body of water but different parts of it have particular designation, Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Antarctic, etc. If we consider the names, there is differentiation, but the water, the ocean itself is one reality. Likewise the divine religions of the holy manifestations of God are in reality one, though in names and nomenclature they differ.102

During his nine-month visit to the United States and Canada — a strenuous tour that saw him traveling constantly up and down the Eastern seaboard into the Chicago heartland and traversing the continent via Montreal, Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Denver to the West Coast before returning to New York — he expounded the fundamental principles of the revelation and teachings of Bahá'u'lláh. He spoke of the equality between men and women, the harmony of science and religion, the need for universal education and a universal language, the independent investigation of truth, the oneness of God, the oneness and continuity of the prophets of God, the oneness of the human race and the elimination of all forms of prejudice and discrimination. The American press gave his tour extensive coverage and his speeches were widely circulated in the daily press. Gibran avidly followed the news of one whom he ardently desired to draw.

'Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to the United States took place just before the outbreak of a war that was to claim ten million lives and maim millions more. He foresaw the cataclysm ahead: "Just now Europe is a battlefield of ammunition, ready for a spark and one spark will set aflame the whole world," and he called for America to raise "the standard of international peace, maintaining that no other country had "greater capacity for such an initial step."103

After being drawn by Gibran on April 19, 1912, 'Abdu'l-Bahá delivered two speeches at Columbia University and at the Bowery mission in New York where he proclaimed his message of unity:

All the divine Manifestations have proclaimed the oneness of God and the unity of mankind.. . The fundamental truth of the Manifestations is peace. This underlies all religion, all justice... Read the Gospel and the other Holy Books. You will find their fundamentals are one and the same. Therefore, unity is the essential truth of religion and, when so understood, embraces all the virtues of the human world.104

Speaking at churches, universities, sanatoriums, literary societies, and synagogues, and addressing Christians, Bahá'ís, Jews, Esperantists, suffragettes, theosophists, students, the sick, and the poor, he often made references to Christ. Gibran, who heard him address an audience at the Astor hotel in New York, found his own reflections on Jesus being in accord with the views being expressed by this great spiritual teacher from the East:

His sword was to be a sword of iron... He did not conquer by the physical power of an iron rod; He conquered the East and the West by the sword of His utterance.., he conquered and subdued the East and West. His conquest was effected through the breaths of the Holy Spirit, which eliminated all boundaries and shone from all horizons.105

Such ideas resonated with Gibran, particularly Abdu'l-Bahá's teachings on the equality of men and women, a theme Gibran was to address in Jesus, the Son of Man. 'Abdu'l-Bahá asserted that men and women must be treated as equals if humanity is to progress:

The world of humanity is possessed of two wings: the male and the female. So long as these two wings are not equivalent in strength, the bird will not fly. Until womankind reaches the same degree as man, until she enjoys the same arena of activity, extraordinary attainment for humanity will not be realized; humanity cannot wing its way to heights of real attainment. When the two wings or parts become equivalent in strength, enjoying the same prerogatives, the flight of man will be exceedingly lofty and extraordinary. Therefore, woman must receive the same education as man and all inequality be adjusted. Thus, imbued with the same virtues as man, rising through all the degrees of human attainment, women will become the peers of men, and until this equality is established, true progress and attainment for the human race will not be facilitated.106

He also spoke about terrible conflicts that had erupted between Christians and Muslims, and in a speech in Brooklyn107 expressed his belief in the essential oneness of religion.108

Gibran's own condemnation of fanaticism, forged in the crucible of his own country's bloody history, was in accord with 'Abdu'l-Bahá's belief Quoting Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke of the horrors of religious prejudice and sectarian hatred:

It is not becoming in man to curse another; it is not befitting that man should attribute darkness to another... all mankind are the servants of one God... There are no people of Satan; all belong to the Merciful. There is no darkness; all is light. All are the servants of God, and man must love humanity from his heart. He must, verily, behold humanity as submerged in the divine mercy.109

Gibran was captivated by 'Abdu'l-Bahá calling him "complete. There are worlds in his soul";11O and he was enthralled and electrified by his life-affirming message:

The station of man is great, very great. God has created man after His own image and likeness. He has endowed him with a mighty power which is capable of discovering the mysteries of phenomena. Through its use man is able to arrive at ideal conclusions instead of being restricted to the mere plane of sense impressions. As he possesses sense endowment in common with the animals, it is evident that he is distinguished above them by his conscious power of penetrating abstract realities. He acquires divine wisdom; be searches out the mysteries of creation; he witnesses the radiance of omnipotence; he attains the second birth.111

When he finally completed his first manuscript it was his longest work. Employing an original scheme — which has been likened to Robert Browning's method in The Ring and the Book114 — Gibran presents seventy-eight different impressions of Jesus imaginatively attributed to his contemporaries, both real and fictitious; "His words and deeds as told and recorded by those who knew Him."

His vision of Christ, as it emerges through these imaginary accounts, is poetical and highly unorthodox, with no pretensions to historical accuracy.115 His Jesus is not born of a virgin, he does not die for our salvation, nor is he resurrected. His miracles are the result of natural phenomena, and he teaches the doctrine of reincarnation, Gibran placing him in the context of other avatars who have walked the earth:

Many times the Christ has come to the world, and He has walked many lands. And always He has been deemed a stranger and a madman.

... Have you not heard of Him at the cross-roads of India? And in the land of the Magi, and upon the sands of Egypt?116

89. "When I meditated upon Jesus I always saw Him either as an infant in the manger seeing His mother Mary's face for the first time, or staring from the crucifix at His mother's face for the last time" (Spiritual Sayings [1963], 27).

90. In "The Crucified" Gibran writes: "Jesus was nor sent here to teach the people to build magnificent churches and temples. He came to make the human heart a temple, and the soul an altar, and the mind a priest" (Secrets of the Heart [1992], 215).

91. In "Khalil the Heretic" Gibran writes of the priest: "He is a hypocrite whom the faithful girded with a fine crucifix which he held above their heads as a sharp sword" (Spirits Rebellious, 103).

92. B.P., 363.

93. "The Crucified," in Secrets of the Heart, 214.

94. "Eventide of the Feast," in ibid., 226.

95. B.P., 338.

96. Ibid., 340.

97. J. and K. Gibran, Life and World, 384.

98. Young, This Man from Lebanon(1945), 102.

99. Naimy, A Biography, 208.

100. Gail, Other People, Other Places, 228.

101. Honnold (ed.), Vignettes, 158.

102. Talk delivered at reception at Metropolitan Temple, Seventh Avenue and Fourteenth Street, New York, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, May 28, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 151.

103. Talk delivered at meeting of International Peace Forum, Grace Methodist Episcopal Church, West 104 Street, New York, by 'Abdul Bahá, May 12, 1912, in ibid., 122, 121.

104. Talk delivered at Earl Hall, Columbia University, New York, by Abdu'l-Bahá, April 19, 1912, in ibid., 32.

105. Talk delivered at Central Congregational Church, Brooklyn, New York, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, June 16, 1912, in ibid., 199, 200.

106. Talk delivered at Hotel Sacramento, California, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Oct. 25, 1912, in ibid., 375.

107. Talk delivered at the Central Congregational Church, Hancock Street, Brooklyn, New York, by Abdu'l-Bahá, June 16,1912, in ibid., 200, 201, 202.

108. "A Poet's Voice," in A Tear and a Smile (1994), 192.

109. Talk delivered at Green Acre, Eliot, Maine, by Abdu'l-Bahá, Aug. 17, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 266.

110. K. G. to M. H., April 16, 1912, Chapel Hill papers.

111. Talk delivered at Green Acre, Eliot, Maine, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Aug. 17, 1912, in Promulgation of Universal Peace, 262-63.

112. A Self-Portrait (1972), 84.

113. Young, This Man from Lebanon (1945), 102-103.

114. Both John Haynes Holmes, the former minister of the Community Church in New York (quoted in J. and K. Gibran, Life and World 390), and Claude Bragdon (in "Modern Prophet from Lebanon," Merely Players, 144) compare Gibran's work with Browning's.

115. Some scholars, such as Joseph Ghougassian, argue that the exegesis, the thinking, and deeds of Gibran's Jesus concur with Christ's personality as depicted by the four evangelists (Wings of Thought, 221).

116. Jesus, the Son of Man, 42, 43.

[page 261]

Jesus' awesome power, a recurrent theme in the book, is described by an unnamed man from the desert: "Men and women fled from before His face, and He moved amongst them as the whirling wind moves on the sand-hills."164 Others portray him as a man who could be patient as "a mountain in the wind," yet also impatient of "men of cunning", a man who "would not be governed."165

Those who heard him speak remembered the beauty and passion of his oratory. Assaph, himself an orator from Tyre, perceived that "when you heard Him your heart would leave you and go wandering into regions not yet visited."166 At her wedding in Cana, Rafca the bride remembered that "His voice enchanted us so that we gazed upon Him as if seeing visions,"167 and a character named Cleopas of Bethroune says, "His voice was like cool water in a land of drought."168

Susannah of Nazareth describes Mary, mother of Jesus, as she awaits her sons imminent death on Good Friday: "At dawn she was still standing among us, like a lone banner in the wilderness wherein there are no hosts."169 Gibran constantly expresses his wonder at the beauty and mystery of womanhood: "Woman shall be forever the womb and the cradle but never the tomb."170 His reverence toward woman, a theme that permeates many of his works, reaches its profoundest and most moving expression in Jesus, the Son of Man, reflecting Gibran's love for the many women in his own life. He had once said to Mary: "Woman has deeper mind that is hers only. We call it intuition. And man uses woman's intuition... Women are better than men. They are kinder, more sensitive, more stable, and have a finer sense about much of life."171 These views bear a striking resemblance to the teachings of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who called women "more tender-hearted, more receptive," possessing "intuition more intense" than men.172

164. Ibid., 89.

165. Ibid., 171.

166. Ibid., 10.

167. Ibid., 30.

168. Ibid., 70.

169. Ibid., 162.

170. Ibid., 167.

171. B.P., 413, 286.

172. Abdu'l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 161.

[page 263]

Echoing his own lifelong belief that Jesus was "the Master Poet," Gibran describes Jesus thus: "Aye, He was a poet whose heart dwelt in a bower beyond the heights... the sovereign of all poets,"185 and in the last essay writes: "Master, Master Poet, Master of our silent desires, The heart of the world quivers with the throbbing of your heart. But it burns not with your song."186

In what is often an unconventional portrayal, Jesus is depicted as having traveled to lands both in the East and the West: Philemon, a Greek apothecary, depicts him as "the Master Physician" who visited India where "the priests revealed to Him the knowledge of all that is hidden in the recesses of our flesh." Again the influence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who called Jesus "the real Physician," is evident — a "physician" who came to heal the world.187Reflecting Gibran's own holistic views on medicine, Philemon witnesses in Jesus a supreme spiritual healer to whom the sacred secrets of another age have been revealed...

185. Jesus, the Son of Man, 80.

186. Ibid., 215.

[page 266]

Was Gibran a Christian? There is no doubt that he had accepted the Christian revelation, taking Jesus as an exemplar and the Bible as a treasury of revealed spiritual and moral truth. However, true to the followers of the Sufi path, he could not accept Christianity as exclusive.215 His was a firm belief in the unity of religion and the unity of being which directed his enthusiastic attention to universal ecumenicalism. His creed involved a diversity of strands of belief: the Upanishads; Syrian Neoplatonism; Judeo-Christian mysticism; Islamic Sufism; and the Bahá'í teachings on universal love and the unity of religion as he heard them from 'Abdu'l-Bahá To these influences can be added those spiritual elements he gleaned from his reading of Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, Ibn al-Farid, and al-Ghazali. He forged his own personal spiritual philosophy in which he would connect all the traditions and join William Blake in declaring that "all religions are one."

215. Jenkins, Christianity, 66-67.

[plate between pages 276-277]

click for larger image

|

|